News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

‘They broke us down’: New Orleans teachers, fired after Katrina, reflect on lives upended

by Michelle Liu and Safura Syed, Verite News, Louisiana Illuminator

August 31, 2025

NEW ORLEANS – When Billie Dolce heard a storm was coming in August 2005, she gathered up the papers she thought she would need for the upcoming school year — learning plans tailored for her special education students at Colton Middle School on St. Claude Avenue, and her classroom attendance rolls.

But she never had a chance to take roll call. Hurricane Katrina and the flooding caused by the failure of the federal levee system devastated the city, shutting down New Orleans schools and scattering students, teachers and their families. Months later, the Orleans Parish School Board fired Dolce and all 7,500 other public school employees, and Dolce never taught again at Colton. The papers she had safeguarded from the hurricane sat among her belongings for the next 20 years, until her husband finally burned them in their backyard this summer.

The firings signaled a drastic shift for public education in the city — and for the educators who made up its workforce. In the months following the storm, the state of Louisiana would take over most of New Orleans’ public school district, rebuilding and reshaping it into what would eventually become the country’s first all-charter school system.

Teachers like Dolce looked on as the schools that had long anchored the city’s neighborhoods, and the identities of the city’s people, changed names and changed hands. The charter system did away with attendance zones, sending children to schools outside of their own neighborhoods. Schools were once under a traditional accountability system overseen by publicly elected school board officials. Now, unelected, nonprofit charter boards made decisions for individual schools.

“They broke us down,” said Dolce, now 73. “Everything. Not just Katrina’s damage to homes and lives, but people’s careers, their idea of how they wanted to plan.”

Those who supported the new system cited the poor pre-Katrina performance of the more than 100 city schools that were subsequently moved under state control, along with the school district’s troubled finances, as reasons for the takeover, or “reform,” as they called it.

In the following years, the reformers pointed to sustained “gains in a wide range of student outcomes,” including better test scores and college entry rates, as signs of their success.

Still, the mass terminations had consequences, veteran educators and community leaders say: for the city’s Black middle class, for its teachers union, and for the classroom experiences of its students. Seasoned educators walked away from their careers in New Orleans, feeling disempowered by the reforms, which effectively dismantled the labor power of teachers in the city. The makeup of the city’s educators became whiter and younger, with programs like Teach for America bringing in teachers with less experience, often fresh out of college.

“It was devastating,” said Beverly Wright, an environmental justice scholar whose uncle was a retired teacher at the time of the storm. “It was destabilizing for the whole community. For New Orleans in particular, it literally lit a match to the middle class of this city. … So much of the wealth that we had came out of working in the public school system.”

Now, two decades after the storm, Verite News spoke with more than a dozen educators to understand how the firings shaped their lives.

Dolce was the department chair for special ed at Colton, where she had worked for three decades. She was the kind of teacher who recognized the needs of her students and worked to fulfill them. She decorated her classroom with abandon, incorporated washboards and clothing lines into lessons about the water cycle, and brought in pomegranates and kiwis for children who’d never tried them before.

She was following in the footsteps of generations of Black teachers in the city. The city’s schools and educators reflected how the city’s Black communities had valued and championed education since the Jim Crow era, said the Rev. Brenda Square, who directed the archives and library at the Amistad Research Center at the time of the storm and who later worked to document city’s shift to charter schools. While some New Orleans schools still bore the names of wealthy 19th century slave owners and segregationists, others were named for Black educators and community leaders who had advocated for schools and students, like Joseph Hardin and Alfred Lawless.

“We had generations of people who were denied the opportunity to go to school to be educated. It was illegal to teach our ancestors to read and write. So education was our opportunity,” said Square, who is Black.

Teaching also served as a steady middle-class job in a city where such jobs could be hard to come by, with a salary that could help buy a house in Gentilly or New Orleans East and put money back into the local economy. By the 2004-2005 school year, teachers made an average of $38,175, according to The Times-Picayune, or about $63,000 in today’s dollars.

Barbara Shelby, a former school psychologist for the district who now works with Wright at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, said the city’s homegrown, veteran teachers were unique in the way they cared for their students.

“Each school was like a family, and they nurtured the kids for generations,” Shelby said. “It wasn’t just a job. It was a calling. I mean, they put their whole heart and soul, their blood, sweat and tears into it.”

Grace Lomba worked as a teacher at Alfred Lawless for 30 years and a guidance counselor at Frederick Douglass High School for eight. Inspired by her own high school guidance counselor, Lomba said she wanted to pass on her good experiences to the next generation.

“They just felt that they could really talk to me about anything, because they knew that whatever we talked about was private,” Lomba said. “We took our kids under our wings, and they trusted us, we trusted them.”

After the storm, Lomba retired. She missed friends and family who had left the city, she said, but most of all, she missed her students.

One of Lomba’s former students, Valda Ridgley, remembers Lomba being “the best teacher ever.” Ridgley, originally from Chicago but with ancestral roots in Louisiana, attended Alfred Lawless Junior High for the two years she lived in New Orleans, between 1978 and 1980. She was enrolled in Lomba’s 7th grade honors English class. Ridgley said Lomba even took her to Catholic church after Ridgley, a Baptist, said she wanted to go to church with her teacher.

The two have stayed in touch over the decades, supporting each other through illnesses and the deaths of loved ones. Even though it’s been 47 years since Ridgley was in the 7th grade, she said she will always think of Lomba as her English teacher.

“She didn’t talk at you, like, ‘I’m the teacher, you’re the student, you listen.’ She actually talked to us and listened to what we had to say,” Ridgley said. “As the young folks say today, she met us where we were. She didn’t talk to us like we were imbeciles. She talked to us like we had some sense.”

The shared identities between students and teachers before Katrina — being Black and from New Orleans — helped uplift kids and remind them that they were capable, Wright said. “I always knew that I could become a teacher,” Wright said, because she only had Black teachers growing up.

By 2005, over 70% of New Orleans public school teachers were Black. Their organizational power was concentrated in their politically influential union, the United Teachers of New Orleans. UTNO’s collective bargaining agreements with the district allowed teachers to negotiate higher salaries and better benefits. The school district also had a transparent pay scale and protections that allowed teachers to stay in their careers for decades, unlike the relatively short-term placements that later became common through Teach for America.

Not everyone saw that power, and those protections, as a net positive. A common line of criticism by the reformers was that the union protected bad teachers along with the good, limiting student and district progress.

Leslie Jacobs, a former member of both the Orleans Parish School board and the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, is often credited as one of the main architects of the New Orleans education-reform model. After Katrina, she was a hugely influential advocate of charter school expansion, and a critic of the local teachers union.

In an interview, Jacobs told Verite News that before Katrina, teachers were caught in a failed system. Dismantling the collective bargaining agreement, a consequence of the turn to the all-charter system, wasn’t an intentional goal of the movement, Jacobs said, and the new system never prevented teachers from unionizing within charter schools.

“It’s a true statement that I’ve never been a fan of collective bargaining, but I’m not banging on the table speaking against it,” Jacobs said.

Jacobs said well-run schools don’t give teachers cause to unionize, because their grievances can be easily remedied by principals, who have more power under charter schools than traditionally run schools. In recent years, teachers within a handful of charter schools have voted to unionize, despite strong pushback from charter leadership.

Wright, and many educators, see the restructuring, which shifted power away from elected officials, differently.

“They were really talking about Black power, the power over the school board, the power over the city,” Wright said.

Reformers also pointed to the school district’s financial woes and its management problems, along with the low academic outcomes of many of its schools, as indicators that the system needed drastic changes.

And in the years leading up to the storm, the district faced increasing scrutiny, with the FBI opening a branch within the Orleans Parish School Board offices to investigate bribery charges between contractors and school board officials, leading to dozens of indictments and convictions.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Before Katrina, the state’s Recovery School District, established by the legislature in 2003, had already taken over a handful of the city’s underperforming schools, tasking charter operations to run them.

After the storm, with the city’s schools effectively shut down, the state moved rapidly. Despite pushback from the teachers union and New Orleans lawmakers — who pointed out that parents displaced by the storm had no say in the matter — in November 2005, at the urging of Gov. Kathleen Blanco, the legislature passed a measure enabling a state takeover.

The new law broadened the definition of what was considered a failing school, expanding it to include any school with performance scores below state average — but applied that new definition only to Orleans Parish schools. Shortly after, the Recovery School District took over 102 out of 117 city schools. By the end of the same month, New Orleans school board officials said that as a result, they would have to fire and terminate health insurance for 7,500 furloughed workers.

Teachers, like other residents of the city, had scattered across the country when the storm hit. Some remembered received letters from the state informing them of their terminations. Others found out about the dissolution of the school system on the news, watching as officials dismissed thousands of New Orleans educators on television.

“They say terminated, I say fired,” said Linda Pichon, a longtime paraprofessional at Lawrence D. Crocker Elementary.

With the loss of their jobs came the loss of health care and income. Family members who relied on that income and coverage suffered, too.

Jackie Brown-Cockerham was in a Texas hospital when she found out she’d lost her job. She was there with her daughter, who was having stomach pains, but the insurance card that she had wasn’t working because she was no longer recognized as an employee. “OK, so what am I supposed to do for my child?” Brown-Cockerham remembered thinking as her daughter sat waiting for care.

Teachers who stayed saw their coworkers leave the city for good, often finding better-paying jobs in the places where they’d evacuated, west to Texas and east to Atlanta. Still, some educators chose to work for the Recovery School District, taking a test mandated by the district’s superintendent to get rehired.

Yvonne Guice, who had taught pre-K at Crocker before the storm, was one of those who returned in 2006. Now, Guice found herself with 27 preschoolers in one classroom, trying to balance lesson plans with the needs of students who had lived through the storm. When it rained, the children gathered around Guice and cried. They wouldn’t let her turn off the lights during naptime.

“You don’t know what they went through, you don’t know what happened, and so you just took it as it came,” Guice said.

By the fall of 2007, about half of the fired New Orleans teachers had returned to work in Louisiana public schools — in Orleans Parish and elsewhere, according to the Education Research Alliance. By 2013, just 22% of the fired teachers were still teaching in New Orleans, with an attrition rate higher than other districts affected by the hurricane.

Educators said that the leaders of charter school reform had villainized teachers, often laying the blame on them for a lack of resources and the district’s shortcomings.

“The least popular cause in town right now must be the resistance of some teachers and their union to the chartering of public schools,” declared James Gill in a November 2005 column for the Times-Picayune.

“Indeed, there is so little sympathy for teachers who feel hard done-by that they might be well advised to pipe down,” Gill wrote. “After all, some of them must share responsibility for the shortcomings of a system that has long cried out for the kind of radical overhaul now in the offing.” (Gill died in 2024.)

“Every ill that the system was going through was the teachers’ fault,” said Cynthia Jordan, who taught at William O. Rodgers and John A. Shaw elementaries before the storm and later worked for the RSD.

Charter advocates argued that the job security and protections offered to teachers by the union and district didn’t help students. “At a charter, we all have to perform to keep our jobs,” said Sharon Clark, the director and principal of Sophie B. Wright High School in a 2012 report. “If teachers at Wright do not perform, I can free up their future to do something else.”

A couple weeks after Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, the New Orleans school board held a meeting in Baton Rouge, where several board members attempted to replace then-superintendent Ora Watson with Bill Roberti, one of the consultants with the New York firm Alvarez and Marsal, which had been brought on to rectify the district’s financial woes before the storm.

The vote was split down racial lines, with the board’s three Black members defeating the effort that day. One of those members, the Rev. Torin Sanders, told the Times-Picayne that the effort, which would’ve demoted Watson, who is Black, in favor of Roberti, who is white, was “clearly” racially motivated. Both he and Watson have suggested state education superintendent Cecil Picard was behind the move. (Picard died in 2007.)

“The state superintendent couldn’t stand me,” Watson said in an interview. “He wanted me out of there because he wanted his plan in.”

The meeting alarmed some of the board’s observers — including a group of principals and their attorney, Willie Zanders, who huddled afterward to talk about what had just happened. That day, the school board also voted to place all district employees on disaster leave. Zanders and the principals began to sense a shift in power.

“So we’re meeting at the coffee shop, and we’re discussing this, and the leaders of the principal group said, ‘We need to consider going to court to stop this,’” Zanders recalled.

Zanders’ and the principals’ challenge evolved into a yearslong court fight on behalf of all 7,500 fired employees — including more than 4,000 teachers, along with paraprofessionals, counselors, bus drivers, and others — over whether their firings had been legal.

In 2012, a district court ruled in favor of the teachers, finding that the school board had wrongly terminated them. An appeals court again sided with the educators, with damages estimated at $1.5 billion, a figure that could have bankrupted the district. The school board appealed the case up to the state’s highest court, which ruled against the teachers, and the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately refused to hear the case in 2015.

“I think this whole charter school transition has avoided putting the microscope on human lives that have been impacted and affected by this drive for change,” Zanders said in an interview, reflecting on the case.

Before the storm, it wasn’t uncommon for teachers to have personal connections with their students. Living in the same neighborhoods, they might have known a student’s aunt or parent before the child came into their classroom — or even to have taught that parent.

“There was a standard you expected of your teacher, and there was a standard your teacher expected of you,” Jordan said. “I lived in the community with my students.”

Educators said that the loss of district schools disrupted the communal and economic fabric of Black neighborhoods, and took power away from citizens living in them.

Now, decisions about how schools are run are determined by charter operators, each run by a private board unimpeded by the democratic process. For formerly unionized teachers, that amounts to less accountability over administrators.

“We have no control over charter schools,” Wright said. “The people on the board, half of us don’t know who they are, but that system has been removed from us, and our children are suffering because of the lack of participation of Black people in the system.”

Last year, OPSB discussed running more direct-run schools when it took over the failing Lafayette Academy, a charter school, to open the public district-run Leah Chase School — the first new traditional school it had opened since the storm. But more recently, the current New Orleans public schools superintendent expressed caution against opening more schools, given the district’s decreasing enrollment numbers and financial difficulties.

Most of the educators Verite News spoke with expressed deep distrust towards charter schools and their leadership hierarchies, even if they returned to work in the new system.

Pichon, a longtime paraprofessional, was first recruited into the job by a principal when she was vice-president of the parent-teachers organization for her children’s school, Thomas Alva Edison Elementary. She spent the next three decades working mostly at Crocker. Pichon was wary of the newcomers, people who hadn’t spent their lives teaching. In the turmoil following the storm, she chose not to return to the classroom.

“Drop of a hat, they’ll let you go,” Pichon said.

The splintered system also made it hard for the United Teachers of New Orleans to reorganize following the storm. Instead of negotiating contracts with one authority, OPSB, they now have to unionize and negotiate under dozens of different charter operators. UTNO’s presence, which once defined the district, is now limited to five unionized schools.

Some educators decided to stay with UTNO, even without a contract, to retain certain union benefits. After the storm, the American Federation of Teachers — the national organization under which UTNO organized — tried to rebuild the union and recruit teachers. Lomba worked with the union to try to get veteran teachers to rejoin the union, but organizing was “a big task, because most of our people were not here,” she said.

Other educators said that without the power of a union backing them during disputes, they were hesitant to go back into the classroom.

Dolce had always tried to advocate for her students and her colleagues, even when it meant pushing back against administrative decisions. After the storm, she heard from other teachers who had returned to the classroom and found that they could now be fired for speaking up.

“I knew I had not gone back for a reason, because I don’t want ‘fired’ to be on my legacy,” Dolce said.

Dolce retired after Katrina, unwilling to go through the hurdles of getting hired by the Recovery School District, though she had planned to keep teaching for several more years. Still, she stayed busy — she tutored, phone-banked for the union and wrote individualized education plans for a friend who was trying to reopen Priestley Junior High, doling out her expertise when asked. She took part in the class-action lawsuit, attending court proceedings.

But she found it hard to let go of Colton. After officials finished renovating the school in 2013, Dolce wanted to see how it had changed, so she contacted administrators with the charter network KIPP, which now runs a school — KIPP Leadership — at the old Colton building. They agreed to let her walk around. As she made her way down the familiar halls, trailed by an employee, Dolce took notice of the upgrades, like touchscreen whiteboards and nicer desks. Finally, Dolce reached her old classroom, where the walls were freshly painted and the teacher’s desk was in a different spot.

She felt a sudden impulse to put her initials somewhere, as if she were one of her own students. Maybe under the ledge of the board, where no one would notice. “But I didn’t do it,” Dolce said. Instead, she turned around and walked away.

This article first appeared on Verite News New Orleans and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://veritenews.org/2025/08/29/katrina-teachers-fired-new-orleans/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } }

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post ‘They broke us down’: New Orleans teachers, fired after Katrina, reflect on lives upended appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a detailed examination of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans public schools, with a focus on the mass firing of teachers and the transformation to an all-charter school system. It highlights the negative impacts on Black educators, union power, and local community control, while presenting critical perspectives on privatization and state takeovers. At the same time, it acknowledges the arguments and intentions of education reform advocates, including their focus on improving academic outcomes and financial stability. The tone is generally empathetic toward displaced teachers and critical of policies that dismantled traditional public school structures, reflecting a center-left standpoint that values public education, labor unions, and racial equity, while recognizing reform efforts motivated by accountability and performance concerns.

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

One way to help local musicians? Pay them to tour. – The Current

SUMMARY: Marcella Simien, a Lafayette native and daughter of zydeco legend Terrance Simien, tours as a Memphis brand ambassador supported by Music Export Memphis, a nonprofit aiding local musicians. Since 2018, Music Export has granted over $170,000 in 2024 alone to help artists tour beyond Memphis, promoting the city while sustaining musicians financially. The program offers grants, business training, and industry exposure, aiming to retain talent locally amid economic challenges and declining venues. Founder Elizabeth Cawein emphasizes music as a sustainable export that benefits the community. Simien credits the support for her career growth, international opportunities, and strong Memphis ties.

Read the full article

The post One way to help local musicians? Pay them to tour. – The Current appeared first on thecurrentla.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Remembering 20 years after Hurricane Katrina

SUMMARY: On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana as a Category 3 storm with 125 mph winds, making landfall in Plaquemines Parish. It became the third most intense U.S. landfalling hurricane, causing massive devastation and loss of life, with impacts still felt 20 years later. Across New Orleans, Jefferson, St. Tammany, St. Charles, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Parishes, officials and first responders reflected on the tragedy, honoring resilience, sacrifice, and ongoing recovery efforts. Leaders emphasized remembrance, community strength, and commitment to building safer, stronger futures while mourning those lost and celebrating the courage of survivors.

Read the full article

The post Remembering 20 years after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on wgno.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

K+20: Katrina showed how crucial federal funding is after a disaster. How much will remain?

by Julie O’Donoghue, Louisiana Illuminator

August 29, 2025

For years after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleanians made the Federal Emergency Management Agency the butt of their bitter jokes.

Anti-FEMA sentiment was so high in Louisiana that local businesses started selling T-shirts a couple of months after the storm lampooning the federal agency with slogans like “Where’s FEMA?” and “FEMA stands for Federal Employees Missing in Action”.

The sentiment is understandable. Almost a half dozen federal investigations launched in the six months after Hurricane Katrina made landfall Aug. 29, 2005 – and turned into the country’s most catastrophic natural disaster – determined FEMA failed in nearly every way to respond to the storm.

“Hurricane Katrina exposed flaws in the structure of FEMA and DHS that are too substantial to mend,” concluded a 2006 U.S. Senate report titled “Hurricane Katrina: A Nation Still Unprepared.”

Yet 20 years after the agency’s feckless Katrina response, some Louisiana leaders find themselves in the awkward position of having to defend FEMA.

President Donald Trump has made it clear he wants the federal government to play less of a role in natural disaster response, raising concerns that state and local governments might need to cover more of their recovery costs.

Such a change would likely affect Louisiana more than almost every other state in the country.

Since Katrina, Louisiana has received more public and individual assistance from FEMA ($12.6 billion) than all states but Florida ($16.6 billion) and New York ($19.4 billion), according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which tracks federal disaster spending.

The money helped Louisiana respond to 25 extreme weather events, including 11 hurricanes, six floods and one ice storm, over the past two decades.

That FEMA figure doesn’t account for all of the money Louisiana has received in the wake of Katrina. There was another $11 billion from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development went to the Road Home program to rebuild housing. All told, the federal government put an unprecedented $76 billion toward Louisiana’s recovery from the 2005 storm.

Louisiana simply wouldn’t be able to handle the financial burden of major disaster response without significant support from the federal government, according to several former state officials interviewed. Storms with far less impact than Katrina have the ability to overwhelm the state’s assets, they said.

If Louisiana has to worry about covering more disaster recovery costs, the state will have less money to spend on schools, universities, roads, bridges and economic development.

“If we didn’t have the federal money, we would be in a terrible mess, and we would have been in a terrible mess from Katrina going forward,” said Jay Dardenne, Louisiana’s former lieutenant governor and state budget chief for former Gov. John Bel Edwards.

Uncertainty at FEMA

To what extent Trump will pull back on federal disaster assistance isn’t clear.

As recently as June, the president said he would push to eliminate FEMA altogether. He then backed off that rhetoric after July 4th weekend flooding in Texas killed at least 136 people, including children attending a sleepaway camp. His administration’s response was directly criticized.

Still, the Trump administration has already made several preliminary changes to FEMA that alarm emergency response experts. The agency has reduced staff and some of those who remain have been asked to help with hiring immigration enforcement agents instead of working on disaster relief.

The FEMA cuts come on top of those to the National Hurricane Center and other federal programs that provide crucial information to hurricane-prone states and help them ready for incoming storms.

Some reforms Congress enacted in the year after Katrina to strengthen FEMA have also been ignored. A law requiring FEMA’s director to have experience in emergency response and disaster recovery isn’t being followed. Trump’s acting FEMA administrator David Richardson previously oversaw counter terrorism programs but does not have natural disaster management experience.

There are also concerns about whether a new policy delayed assistance during the Texas flood, similar to what unfolded in the aftermath of Katrina.

Due to a bureaucratic breakdown 20 years ago, FEMA failed to promptly provide boats for search-and-rescue teams in New Orleans, even after federal officials knew flooding was widespread, according to a U.S. Senate report from 2006.

This past July, several questions were raised about whether search-and-rescue teams were delayed during the Texas flood because Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem now requires every FEMA contract over $100,000 to be approved personally by her, the Associated Press reported. The Trump administration has denied those allegations.

The ability of Louisiana and other states to respond to catastrophic weather with their own staff would also likely be impacted if Trump changes the traditional funding reimbursements for recovery efforts.

“The federal government will have a lasting role in responding to and funding the impact of disasters; local and state governments simply do not have the resources to do so,” said Paul Rainwater, who was executive director of the Louisiana Recovery Authority that managed federal funding for state rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Katrina. He went on to serve as former Gov. Bobby Jindal’s chief of staff and budget czar.

“The question the Trump administration faces, given some of its comments about FEMA, is: When will a White House step in and help?” he said.

Presidential discretion

The president has a significant say in when FEMA provides funding to states after natural disasters, as well as how much money states or local governments receive.

When a state is overwhelmed by a catastrophic event, a governor makes a formal request of the president for federal assistance. FEMA starts to provide help to the state authorities after it is granted.

Since returning to office in January, Trump has denied disaster relief that was expected to be approved. His decisions have affected liberal-leaning states such as Maryland and Washington and more conservative ones like West Virginia.

He even stalled for a month on accepting a disaster declaration from Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who personally knows Trump and served as his press secretary during his first term as president.

As president, Trump has the ability to not only approve federal assistance, but to also increase the share of the state or local costs that FEMA will reimburse. For example, federal law gives presidents the discretion to reduce or waive the requirement for a state or local government to cover 25% of the cost of debris removal after a storm.

Louisiana has benefited from a reduction of these local financial responsibilities for nine weather events in the past 25 years, including for hurricanes Ida (2021), Laura (2020), Ike (2008), Gustav (2008), Rita (2005), Katrina (2005) and Ivan (2004). The 2016 Baton Rouge-area floods and a severe ice storm in 2001 were also approved for enhanced federal assistance, according to a 2023 Congressional report.

But all the upheaval should be a signal to local and state officials to prepare as if that extra FEMA help might not be coming their way, former FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell, who worked for President Joe Biden, said in a call with reporters this week.

“There are, right now, a lot of questions about whether any of those costs are going to be eligible for reimbursement,” Criswell said. “You need to put plans in place to make sure that you can do it, regardless of whether you get federal support.”

U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., said he personally advocated for the federal government to cover more disaster recovery bills after Hurricane Laura, which hit Southwest Louisiana, and the 2016 flooding.

Sometimes a disaster is so profound that local governments have a hard time coming up with the tax revenue to cover their share of the recovery. If people lose their homes and are displaced, as happened after Katrina, cities and parishes won’t have much money to put toward cleanup, Cassidy said.

“When you destroy a community, you destroy their ability to raise tax money,” he said in an interview.

Jindal, who served as Louisiana’s governor from 2008-16 and was a congressman during Hurricane Katrina, said he thinks the federal government will always be an important partner in major disasters. But states and local governments should take on more responsibility for smaller events.

“There are many day-to-day disasters that many state and local governments can handle themselves,” Jindal said. “For the bigger disasters that can overwhelm, you still want to have some federal role.”

It’s also crucial that local and state officials know what to expect from the federal government so they can be prepared, said Jindal, who was governor when hurricanes Gustav and Ike hit Louisiana.

“I think it’s important to have clear rules ahead of time,” he said.

Landry: Louisiana shouldn’t worry about FEMA

Trump may have denied disaster relief to other states, but Gov. Jeff Landry said Louisiana has nothing to worry about when it comes to FEMA because of his good relationship with the administration.

“I think it’s all just a bunch of media hype trying to scare people. We’re ready for hurricane season,” the governor told reporters this week.

Landry has a close relationship with Noem and said Trump’s homeland security leader has already responded to requests for assistance for matters in Lake Charles and Terrebonne Parish this year.

“What Kristi Noem has done lately, I mean, we just call her, and we say, ‘These are projects that need to be moved,’” Landry said.

Louisiana is one of only a few states that has a local representative on Trump’s FEMA review council, which is supposed to make recommendations on reforming the agency this fall.

One of the council’s 12 members, who include Noem and Department of Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, is Louisiana native Mark Cooper, Jindal’s former head of emergency management and former Gov. Edwards’ chief of staff.

“Obviously, Louisiana is playing a big role in this reimagining for FEMA,” Cooper said this week in an interview from Oklahoma where the review council was meeting. “We’re being heard. Louisiana is being heard as part of this process.”

Cooper said the council already met directly with Louisiana emergency response officials in the Landry administration. It held its second public meeting in New Orleans in July at his suggestion.

The council has made no decisions about whether FEMA’s reimbursement policies for state and local governments should change, Cooper said, but he suggested more might be asked of states.

“We need to do more to help states to be more self-reliant and resilient,” he said.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post K+20: Katrina showed how crucial federal funding is after a disaster. How much will remain? appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of federal disaster relief, particularly regarding FEMA, while highlighting the ongoing necessity and benefit of federal assistance for disaster-prone states such as Louisiana. It underscores the shortcomings and controversial decisions under Trump, including staffing cuts and hesitance to approve disaster aid, often citing sources and officials who lean toward advocating for stronger government roles in disaster recovery. While it provides some conservative perspectives, such as Governor Landry’s and former Governor Jindal’s comments about state responsibility and positive relations with the current administration, the overall tone emphasizes support for federal involvement and skepticism toward efforts to reduce it—both typical of center-left media framing that stresses government responsibility in social support systems.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Racism Wrapped in Rural Warmth

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Child in north Alabama has measles, says Alabama Department of Public Health

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

After the Winds: Kindness in Katrina’s Wake

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Southwest Airlines is changing its seating policy for larger customers

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

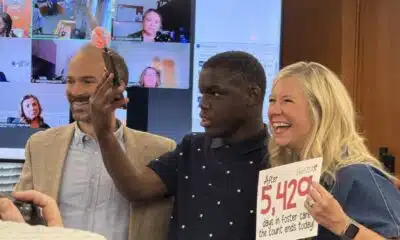

‘This is what we all work for’: Longest term foster child in Arkansas adopted

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Fever Five: Top highlights from Friday night’s high school football games (Week 1: Jamboree Edition)

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

DC teachers cheer ‘Not Like Us’ parody and $1,100 donation | NBC4 Washington

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Environmental advocates file petition for rehearing in Glynn County wetlands case