News from the South - Texas News Feed

Texas traffic stop could lead to migrant’s deportation

An immigrant faces deportation after a routine traffic stop in Texas, sparking more fear

“An immigrant faces deportation after a routine traffic stop in Texas, sparking more fear” was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

A week ago, 29-year-old Jose Alvaro and his wife Ashley went out to buy some baby formula in Lubbock with their three kids when a police officer pulled them over for a problem with the vehicle’s license plate. The traffic stop has upended the family’s life.

The officer was “really nice and kind” when he approached them and Ashley explained that her husband didn’t speak much English and didn’t have a driver’s license, Ashley remembers. Jose Alvaro, who migrated to the U.S. from Central America and is undocumented, gave the officer his proof of insurance and his passport.

The officer then called U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Ten minutes later, multiple vehicles filled with federal immigration authorities pulled up behind the patrol car, Ashley and her lawyer said. The agents swarmed the family’s vehicle and took Jose Alvaro to a detention center for processing.

Inside the vehicle, his 4-year-old son Antonio began to cry and asked, “What are they doing?” Ashley said.

Jose Alvaro had been navigating the long, costly and cumbersome process of applying for a green card. Now he faces deportation proceedings and his family’s future is unclear. ICE did not respond to a request for comment.

“I am terrified,” said Ashley, 22, an American citizen who asked her and her relatives’ last names not be published because she’s worried immigration authorities could retaliate against her husband.

As President Donald Trump begins his promised crackdown on illegal immigration, the incident highlights immigrant rights advocates’ fears that routine interactions with local law enforcement officers could more frequently lead to deportation for undocumented people who don’t have criminal histories.

Trump’s immigration adviser Tom Homan has said that the administration would prioritize immigrants with criminal records. On Tuesday, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said that undocumented people who have committed “heinous acts” should be prioritized by ICE — but that anyone who has entered the country illegally has committed a crime and faces deportation under the Trump administration.

“Two things can be true at the same time,” Leavitt said. “Illegal criminal drug dealers, the rapists, the murderers, the individuals who have committed heinous acts on the interior of our country and who have terrorized law-abiding American citizens, absolutely, those should be the priority of ICE, but that doesn’t mean that the other illegal criminals who enter our nation’s borders are off the table.”

The situation illustrates the contrasting approaches to immigration enforcement between the Biden and Trump administrations, said Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute office at New York University School of Law. During the Biden administration, immigration authorities narrowed their targets to immigrants who committed serious crimes and recent arrivals at the southwest border, while Trump’s recent moves suggest that “everyone is game,” Chishti said.

“Enforcement is now random, everyone is subject to enforcement action,” Chishti said. “You can imagine what fear it instills just as one incident.”

Ashley and the family’s lawyer, Kate Lincoln-Goldfinch, said that Jose Alvaro had no criminal record; online court records show no criminal history for him.

In his first week in office, Trump gave immigration agencies a daily quota for arrests and directed federal prosecutors to investigate local officials who interfere with the administration’s immigration agenda. But that doesn’t compel police to call federal agents when they encounter an undocumented person.

Get the data and visuals that accompany this story →

State leaders may try to change that. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick on Wednesday said requiring local authorities to help federal deportation efforts was one of his legislative priorities for the current legislative session.

“There are lots of local police around the state of Texas and around the country who are anxious and excited to work with ICE,” said Denise Gilman, a law professor who directs the Immigration Clinic at the University of Texas at Austin and represented people in similar situations during Trump’s first term in office. “The consequences are very grave for somebody who has been living and working in the United States.”

It’s unclear how often Texas police call ICE when they stop an undocumented person. Some large Texas police departments had policies that limited when officers asked about a person’s legal status or honored requests from ICE to hold a person for deportation — an effort to build trust within immigrant communities so they wouldn’t fear calling police to report crimes.

The potential legislation Patrick announced Wednesday in his priority list could go further than a 2017 state law that says local officers can’t be barred from asking a person’s legal status. Some cities remain friendlier to undocumented people than others: Austin police officers are required to tell a detained person that they don’t have to answer before asking them about their immigration status. In Houston, Mayor John Whitmire said this week that Houston police have not helped federal agents carry out deportations.

Lubbock Police Department spokesperson Lt. Brady Cross, who confirmed that the officer called ICE during the traffic stop, said department policy says officers have discretion to notify federal authorities about crimes that fall under their jurisdiction.

Lubbock police “may not detain or arrest only because they suspect someone may be an illegal alien and may not detain them longer than any other suspect,” Cross said. “While the department’s primary function is to enforce the laws of the state of Texas and the ordinances of the city of Lubbock, at times there will be a crossover with federal law; the LPD will not stand in the way of federal partners.”

Hurricane romance

Ashley and Jose Alvaro met after a natural disaster. In 2018, Hurricane Michael peeled the roof off Ashley’s family’s home in the Florida panhandle, Ashley said.

Jose Alvaro was one of the roofers who repaired it. In their first interaction, he held up three fingers and asked, agua? Ashley returned with three water bottles, and he smiled at her.

The two began talking, then dating. After a while, Antonio came along.

“It was the best feeling in the world watching him see his son for the first time,” Ashley said, remembering the biggest smile she’d ever seen on Jose Alvaro’s face and a tear slipping out of his eye.

Since then they had two other children: Ariceli, 1, and Jose, 6 months. All three were born in the U.S. They moved to Lubbock where Jose Alvaro had found steady work. Lincoln-Goldfinch declined to say how Jose Alvaro entered the country for fear that it may hurt his deportation case.

The family eventually settled in a house in Texas’ 10th largest city, where roughly one-third of the population is Latino, according to Census estimates.

Waiting in the car for hours

When the family went out last week to run their errand in Lubbock, Jose Alvaro missed a turn, Ashley said. When he turned around, they spotted a police officer at a red light. The officer pulled them over “not even 10 seconds later,” she said.

Kasie Davis, a Lubbock police spokesperson, said in an email that a person’s criminal history is “not used as a basis of arrest or not; or in this case, the notification of federal authorities.”

Davis referred further questions to ICE.

After taking Jose Alvaro into custody, an immigration agent told Ashley she was free to go, but she did not know how to drive or have a license. She said she had two diapers and no formula for the baby. As the agents whisked Jose Alvaro away, Antonio asked again what was happening to his dad.

She tried to explain the basics: Passport, immigration agents. But he’s four.

Fear settled in and she thought, they’re deporting him.

After the agents took Jose Alvaro to a detention center, Ashley said she stayed in the car with the kids for about three and a half hours. She said people began harassing her for sitting in a parked car in their neighborhood for so long.

The agents had told her that if she wanted her husband returned to the same spot, she would have to wait where she was, she said. So she did.

“In my head, I’m just trying to cooperate with them,” Ashley said. “Trying to think of the easiest way for them to get him back to me. So I’m agreeing with everything that they’re saying.”

“Inefficient and foolish”

When Jose Alvaro was detained by ICE, Goldfinch, the lawyer, was already representing the family as they navigated the process of trying to get permanent residency, also known as a green card, for Jose Alvaro, which can take years, she said.

“It takes a very long time,” Goldfinch said, lamenting that he is now another number in an overwhelmed court system on top of being in line for a green card. “It’s a really inefficient and foolish way for the government to be handling issues.”

After Ashley had sat with her kids in their car for more than three hours, the agents returned with Jose Alvaro and told him that he’ll have two hearings and a court date for his removal proceedings, the next in Dallas.

She thinks about Antonio and Ariceli, who don’t fall asleep unless they are next to their dad. Terrified of ICE showing up at their door, the family does not answer when there’s a knock at the door. They peek out the window whenever they hear any sound, Ashley said.

Ashley has looked for plane tickets to Dallas for her husband’s first court hearing in March, but she doesn’t know how many return flights to book.

“I’m scared,” Ashley said, breaking down over the telephone.

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2025/01/29/texas-immigration-lubbock-police-traffic-stop-ice-deportation/.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Frustrated with poor play against UTEP, Arch Manning will 'get back to basics'

SUMMARY: Texas quarterback Arch Manning and coach Steve Sarkisian acknowledge the team’s underwhelming offensive performance in a 27-10 win over UTEP. Manning completed 11 of 25 passes for 114 yards with a touchdown and an interception, frustrating fans expecting a stronger showing at home. Despite a rough first half with 10 consecutive incompletions, Manning showed flashes of promise and scored twice on the ground. Sarkisian emphasized Manning’s mental struggle rather than physical injury and expressed confidence in his growth and consistency. Manning committed to improving fundamentals and handling in-game pressure ahead of tougher matchups, including their SEC opener against Florida on Oct. 4.

The post Frustrated with poor play against UTEP, Arch Manning will 'get back to basics' appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Texas nursing students return from life-changing internship in Africa

SUMMARY: Two Texas nursing students, Tom Strandwitz and Valerie Moon, participated in Mercy Ships’ inaugural nursing internship aboard the Africa Mercy hospital ship in Madagascar. Selected from nationwide applicants, they gained hands-on experience in various departments, providing free surgeries and care in underserved regions. Their travel expenses were covered by over $11,000 raised through community GoFundMe campaigns. Both students were deeply impacted by patient interactions, such as cataract surgeries restoring sight and building trust with families. The internship broadened their perspectives on global health care. They plan to continue careers in intensive care and public health, with hopes to return to international nursing missions.

Read the full article

The post Texas nursing students return from life-changing internship in Africa appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Austin becoming FEMA-approved emergency alert authority, planning 1st test alert

SUMMARY: On Monday, Sept. 29, Austin will conduct a test of the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS), becoming a FEMA-approved alerting authority able to send emergency alerts via Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) to cell phones and Emergency Alert System (EAS) messages to TV and radio. This coordinated test at 3 p.m. will cover the city across its three counties—Travis, Hays, and Williamson. The alerts will clearly indicate a test and require no action. IPAWS allows authenticated, geotargeted emergency notifications without subscription, enhancing public safety communication. More details are available at ReadyCentralTexas.org and Ready.gov/alerts.

The post Austin becoming FEMA-approved emergency alert authority, planning 1st test alert appeared first on www.kxan.com

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

The Center Square7 days ago

California mother says daughter killed herself after being transitioned by school | California

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Zaxby's Player of the Week: Dylan Jackson, Vigor WR

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas medical marijuana sales on pace for record year

-

Local News Video7 days ago

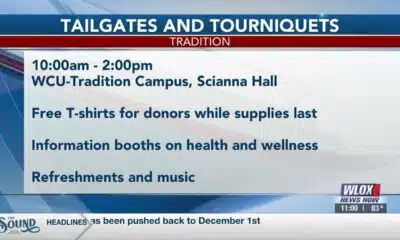

William Carey University holds 'tailgates and tourniquets' blood drive

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Local, statewide officials react to Charlie Kirk death after shooting in Utah

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

What we know about Charlie Kirk shooting suspect, how he was caught

-

Local News6 days ago

US stocks inch to more records as inflation slows and Oracle soars