Grace McCormack, University of Southern California and Erin Duffy, University of Southern California

Medicare Advantage – the commercial alternative to traditional Medicare – is drawing down federal health care funds, costing taxpayers an extra 22% per enrollee to the tune of US$83 billion a year.

Medicare Advantage, also known as Part C, was supposed to save the government money. The competition among private insurance companies, and with traditional Medicare, to manage patient care was meant to give insurance companies an incentive to find efficiencies. Instead, the program’s payment rules overpay insurance companies on the taxpayer’s dime.

We are health care policy experts who study Medicare, including how the structure of the Medicare payment system is, in the case of Medicare Advantage, working against taxpayers.

Medicare beneficiaries choose an insurance plan when they turn 65. Younger people can also become eligible for Medicare due to chronic conditions or disabilities. Beneficiaries have a variety of options, including the traditional Medicare program administered by the U.S. government, Medigap supplements to that program administered by private companies, and all-in-one Medicare Advantage plans administered by private companies.

Commercial Medicare Advantage plans are increasingly popular – over half of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in them, and this share continues to grow. People are attracted to these plans for their extra benefits and out-of-pocket spending limits. But due to a loophole in most states, enrolling in or switching to Medicare Advantage is effectively a one-way street. The Senate Finance Committee has also found that some plans have used deceptive, aggressive and potentially harmful sales and marketing tactics to increase enrollment.

Baked into the plan

Researchers have found that the overpayment to Medicare Advantage companies, which has grown over time, was, intentionally or not, baked into the Medicare Advantage payment system. Medicare Advantage plans are paid more for enrolling people who seem sicker, because these people typically use more care and so would be more expensive to cover in traditional Medicare.

However, differences in how people’s illnesses are recorded by Medicare Advantage plans causes enrollees to seem sicker and costlier on paper than they are in real life. This issue, alongside other adjustments to payments, leads to overpayment with taxpayer dollars to insurance companies.

Some of this extra money is spent to lower cost sharing, lower prescription drug premiums and increase supplemental benefits like vision and dental care. Though Medicare Advantage enrollees may like these benefits, funding them this way is expensive. For every extra dollar that taxpayers pay to Medicare Advantage companies, only roughly 50 to 60 cents goes to beneficiaries in the form of lower premiums or extra benefits.

As Medicare Advantage becomes increasingly expensive, the Medicare program continues to face funding challenges.

In our view, in order for Medicare to survive long term, Medicare Advantage reform is needed. The way the government pays the private insurers who administer Medicare Advantage plans, which may seem like a black box, is key to why the government overpays Medicare Advantage plans relative to traditional Medicare.

Paying Medicare Advantage

Private plans have been a part of the Medicare system since 1966 and have been paid through several different systems. They garnered only a very small share of enrollment until 2006.

The current Medicare Advantage payment system, implemented in 2006 and heavily reformed by the Affordable Care Act in 2010, had two policy goals. It was designed to encourage private plans to offer the same or better coverage than traditional Medicare at equal or lesser cost. And, to make sure beneficiaries would have multiple Medicare Advantage plans to choose from, the system was also designed to be profitable enough for insurers to entice them to offer multiple plans throughout the country.

To accomplish this, Medicare established benchmark estimates for each county. This benchmark calculation begins with an estimate of what the government-administered traditional Medicare plan would spend on the average county resident. This value is adjusted based on several factors, including enrollee location and plan quality ratings, to give each plan its own benchmark.

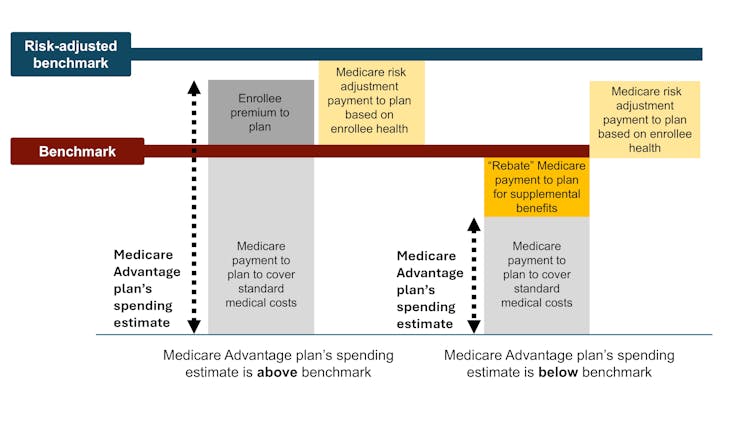

Medicare Advantage plans then submit bids, or estimates, of what they expect their plans to spend on the average county enrollee. If a plan’s spending estimate is above the benchmark, enrollees pay the difference as a Part C premium.

Most plans’ spending estimates are below the benchmark, however, meaning they project that the plans will provide coverage that is equivalent to traditional Medicare at a lower cost than the benchmark. These plans don’t charge patients a Part C premium. Instead, they receive a portion of the difference between their spending estimate and the benchmark as a rebate that they are supposed to pass on to their enrollees as extras, like reductions in cost-sharing, lower prescription drug premiums and supplemental benefits.

Finally, in a process known as risk adjustment, Medicare payments to Medicare Advantage health plans are adjusted based on the health of their enrollees. The plans are paid more for enrollees who seem sicker.

The government pays Medicare Advantage plans based on Medicare’s cost estimates for a given county. The benchmark is an estimate from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services of what it would cost to cover an average county enrollee in traditional Medicare, plus adjustments including quartile payments and quality bonuses. The risk-adjusted benchmark also takes into consideration an enrollee’s health. Samantha Randall at USC, CC BY-ND

Theory versus reality

In theory, this payment system should save the Medicare system money because the risk-adjusted benchmark that Medicare estimates for each plan should run, on average, equal to what Medicare would actually spend on a plan’s enrollees if they had enrolled in traditional Medicare instead.

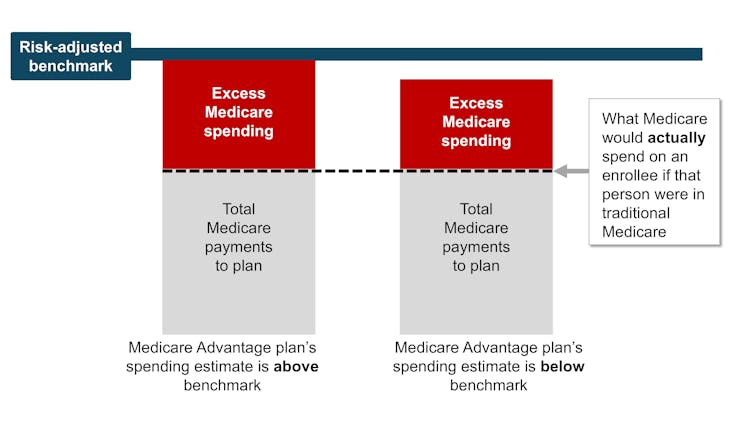

In reality, the risk-adjusted benchmark estimates are far above traditional Medicare costs. This causes Medicare – really, taxpayers – to spend more for each person who is enrolled in Medicare Advantage than if that person had enrolled in traditional Medicare.

Why are payment estimates so high? There are two main culprits: benchmark modifications designed to encourage Medicare Advantage plan availability, and risk adjustments that overestimate how sick Medicare Advantage enrollees are.

High risk-adjusted benchmarks lead to overpayments from the government to the private companies that administer Medicare Advantage plans. Samantha Randall at USC, CC BY-ND

Benchmark modifications

Since the current Medicare Advantage payment system started in 2006, policymaker modifications have made Medicare’s benchmark estimates less tied to what the plan spends on each enrollee.

In 2012, as part of the Affordable Care Act, Medicare Advantage benchmark estimates received another layer: “quartile adjustments.” These made the benchmark estimates, and therefore payments to Medicare Advantage companies, higher in areas with low traditional Medicare spending and lower in areas with high traditional Medicare spending. This benchmark adjustment was meant to encourage more equitable access to Medicare Advantage options.

In that same year, Medicare Advantage plans started receiving “quality bonus payments” with plans that have higher “star ratings” based on quality factors such as enrollee health outcomes and care for chronic conditions receiving higher bonuses.

However, research shows that ratings have not necessarily improved quality and may have exacerbated racial inequality.

Even before fully taking into account risk adjustment, recent estimates peg the benchmarks, on average, as 8% higher than average traditional Medicare spending. This means that a Medicare Advantage plan’s spending estimate could be below the benchmark and the plan would still get paid more for its enrollees than it would have cost the government to cover those same enrollees in traditional Medicare.

Overestimating enrollee sickness

The second major source of overpayment is health risk adjustment, which tends to overestimate how sick Medicare Advantage enrollees are.

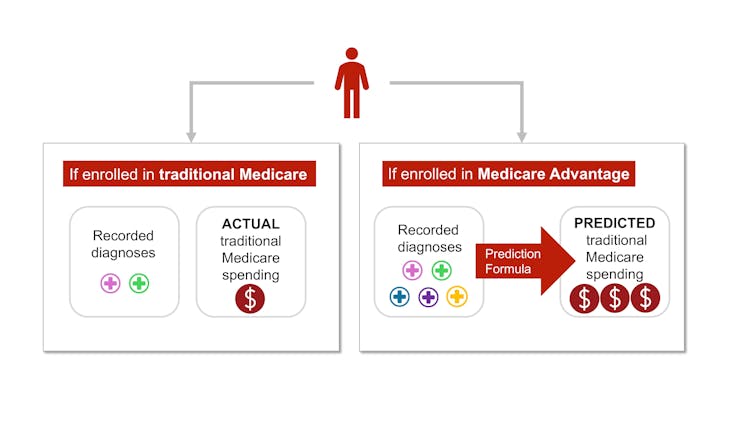

Each year, Medicare studies traditional Medicare diagnoses, such as diabetes, depression and arthritis, to understand which have higher treatment costs. Medicare uses this information to adjust its payments for Medicare Advantage plans. Payments are lowered for plans with lower predicted costs based on diagnoses and raised for plans with higher predicted costs. This process is known as risk adjustment.

But there is a critical bias baked into risk adjustment. Medicare Advantage companies know that they’re paid more if their enrollees seem more sick, so they diligently make sure each enrollee has as many diagnoses recorded as possible.

This can include legal activities like reviewing enrollee charts to ensure that diagnoses are recorded accurately. It can also occasionally entail outright fraud, where charts are “upcoded” to include diagnoses that patients don’t actually have.

In traditional Medicare, most providers – the exception being Accountable Care Organizations – are not paid more for recording diagnoses. This difference means that the same beneficiary is likely to have fewer recorded diagnoses if they are enrolled in traditional Medicare rather than a private insurer’s Medicare Advantage plan. Policy experts refer to this phenomenon as a difference in “coding intensity” between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.

The same person is likely to be documented with more illnesses if they enroll in Medicare Advantage rather than traditional Medicare – and cost taxpayers more money. Samantha Randall at USC, CC BY-ND

In addition, Medicare Advantage plans often try to recruit beneficiaries whose health care costs will be lower than their diagnoses would predict, such as someone with a very mild form of arthritis. This is known as “favorable selection.”

The differences in coding and favorable selection make beneficiaries look sicker when they enroll in Medicare Advantage instead of traditional Medicare. This makes cost estimates higher than they should be. Research shows that this mismatch – and resulting overpayment – is likely only going to get worse as Medicare Advantage grows.

Where the money goes

Some of the excess payments to Medicare Advantage are returned to enrollees through extra benefits, funded by rebates. Extra benefits include cost-sharing reductions for medical care and prescription drugs, lower Part B and D premiums, and extra “supplemental benefits” like hearing aids and dental care that traditional Medicare doesn’t cover.

Medicare Advantage enrollees may enjoy these benefits, which could be considered a reward for enrolling in Medicare Advantage, which, unlike traditional Medicare, has prior authorization requirements and limited provider networks.

However, according to some policy experts, the current means of funding these extra benefits is unnecessarily expensive and inequitable.

It also makes it difficult for traditional Medicare to compete with Medicare Advantage.

Traditional Medicare, which tends to cost the Medicare program less per enrollee, is only allowed to provide the standard Medicare benefits package. If its enrollees want dental coverage or hearing aids, they have to purchase these separately, alongside a Part D plan for prescription drugs and a Medigap plan to lower their deductibles and co-payments.

Medicare Advantage plans offer extras, but at a high cost to the Medicare system – and taxpayers. Only 50-60 cents of a dollar spent is returned to enrollees as decreased costs or increased benefits.

The system sets up Medicare Advantage plans to not only be overpaid but also be increasingly popular, all on the taxpayers’ dime. Plans heavily advertise to prospective enrollees who, once enrolled in Medicare Advantage, will likely have difficulty switching into traditional Medicare, even if they decide the extra benefits are not worth the prior authorization hassles and the limited provider networks. In contrast, traditional Medicare typically does not engage in as much direct advertising. The federal government only accounts for 7% of Medicare-related ads.

At the same time, some people who need more health care and are having trouble getting it through their Medicare Advantage plan – and are able to switch back to traditional Medicare – are doing so, according to an investigation by The Wall Street Journal. This leaves taxpayers to pick up care for these patients just as their needs rise.

Where do we go from here?

Many researchers have proposed ways to reduce excess government spending on Medicare Advantage, including expanding risk adjustment audits, reducing or eliminating quality bonus payments or using more data to improve benchmark estimates of enrollee costs. Others have proposed even more fundamental reforms to the Medicare Advantage payment system, including changing the basis of plan payments so that Medicare Advantage plans will compete more with each other.

Reducing payments to plans may have to be traded off with reductions in plan benefits, though projections suggest the reductions would be modest.

There is a long-running debate over what type of coverage should be required under both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Recently, policy experts have advocated for introducing an out-of-pocket maximum to traditional Medicare. There have also been multiple unsuccessful efforts to make dental, vision, and hearing services part of the standard Medicare benefits package.

Although all older people require regular dental care and many of them require hearing aids, providing these benefits to everyone enrolled in traditional Medicare would not be cheap. One approach to providing these important benefits without significantly raising costs is to make these benefits means-tested. This would allow people with lower incomes to purchase them at a lower price than higher-income people. However, means-testing in Medicare can be controversial.

There is also debate over how much Medicare Advantage plans should be allowed to vary. The average Medicare beneficiary has over 40 Medicare Advantage plans to choose from, making it overwhelming to compare plans. For instance, right now, the average person eligible for Medicare would have to sift through the fine print of dozens of different plans to compare important factors, such as out-of-pocket maximums for medical care, coverage for dental cleanings, cost-sharing for inpatient stays, and provider networks.

Although millions of people are in suboptimal plans, 70% of people don’t even compare plans, let alone switch plans, during the annual enrollment period at the end of the year, likely because the process of comparing plans and switching is difficult, especially for older Americans.

MedPAC, a congressional advising committee, suggests that limiting variation in certain important benefits, like out-of-pocket maximums and dental, vision and hearing benefits, could help the plan selection process work better, while still allowing for flexibility in other benefits. The challenge is figuring out how to standardize without unduly reducing consumers’ options.

The Medicare Advantage program enrolls over half of Medicare beneficiaries. However, the $83-billion-per-year overpayment of plans, which amounts to more than 8% of Medicare’s total budget, is unsustainable. We believe the Medicare Advantage payment system needs a broad reform that aligns insurers’ incentives with the needs of Medicare beneficiaries and American taxpayers.

This article is part of an occasional series examining the U.S. Medicare system.

Past articles in the series:

Grace McCormack, Postdoctoral researcher of Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California and Erin Duffy, Research Scientist and Director of Research Training in Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.