News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Rural hospitals in NC face pressures to cut women’s services

Financial pressures prompt women’s services cuts at NC rural hospitals

Financial pressures on rural hospitals keep some North Carolina facilities from adequately serving pregnant women, new mothers and babies, but that isn’t the full picture.

Workforce shortages and demographic shifts — coupled with a lack of regulatory requirements and policy support — compound the problem, further distancing women from the care they need.

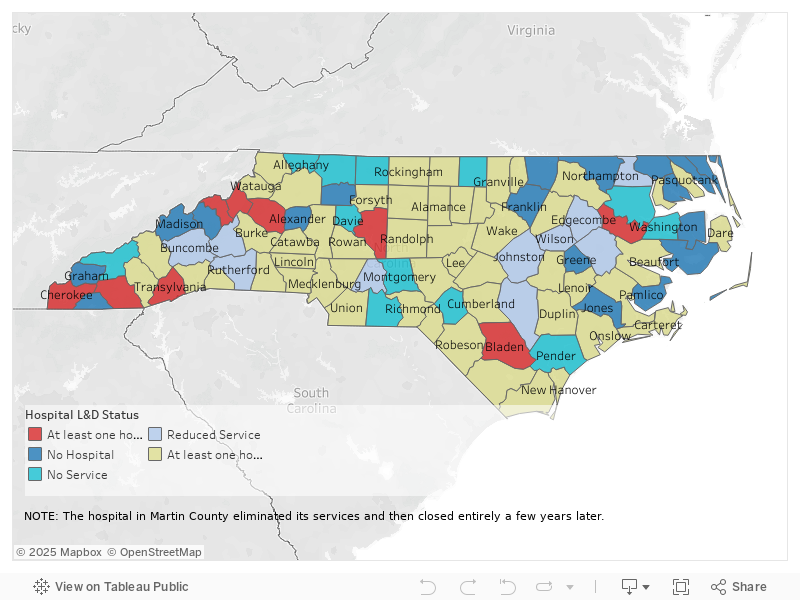

This is part two of the three-part Carolina Public Press investigation, Deserting Women, examining state data on every hospital in North Carolina over the last decade. CPP found that hospital systems have systematically centralized services in urban areas while often cutting them in rural ones, cementing maternal health care deserts in nearly every corner of the state.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ alerts and weekend roundup newsletters]

This article looks closely at the root causes of the problem. Part one examined the data for loss of women’s health services and the potential impact. The third article will address potential solutions.

Allison Rollans, owner of High Country Doulas, witnessed the abandonment of rural mothers up close at a birth at a rural Western North Carolina hospital in 2024.

One of her clients had a Cesarean birth, and afterwards, a single nurse was there to care for both mother and baby. Neither received the level of post-birth care that Rollans or the new mother expected. Rollans asked how this could be. The nurse told her that another nurse had just been cut from the shift rotation due to a research analysis that showed low numbers of births in the area in the preceding months.

Maintaining specialized, 24/7 staff, up-to-date equipment, and adequate space for a labor and delivery unit, also called a maternity ward, generates substantial expenses. If a hospital begins to see declining numbers of births, due to an aging or shrinking population in the area, per-birth costs increase dramatically.

No regulatory structure exists in North Carolina to keep hospitals from balancing pesky financial equations like this by reducing, or fully eliminating, maternity and other related care, even when they previously received a certificate of need from the state to provide that care.

Most hospitals in the state are governmental, educational and/or nonprofit, which means their pursuit of health care is supposed to come before the balance sheet. Even so, they can’t afford to lose too much money, or their ability to provide other services could suffer.

Financial pressure for NC rural hospitals

Labor and delivery units are known in the hospital business as a “loss leader” — they typically do not bring in any profit. Usually, drawing new patients who will become loyal families provides hospitals with a justification for the high cost of operating a maternity ward. Those patients will likely use other, more profitable, services at the hospital over time.

The fundamental problem of maternity care is that the cost of maintaining service is fixed, regardless of patient volume.

When rural hospitals in North Carolina begin cutting services of any type, labor and delivery units are often the first to go. Closing maternity wards has sometimes served as a warning sign of deeper financial troubles to come. This was the case in Martin County, where the hospital eliminated labor and delivery services a few years before closing entirely.

“If you’re averaging one or two deliveries a day, potentially you could go a couple days without deliveries, but you still have to staff,” said Dolly Pressley Byrd, chair of the obstetrics and gynecology department at the Asheville-based Mountain Area Health Education Center, or MAHEC.

“The staffing guidelines are pretty stringent. The recommendation is one-to-one staffing. The model is really expensive, and tricky.”

Employing sufficient nurses offers one challenge. But to staff labor and delivery units, hospitals need to have enough physicians, anesthesiologists, lactation consultants and neonatal intensive care unit staff on call. If the labor and delivery unit doesn’t have enough patients coming and going, paying those salaries starts to stack up against the relatively meager revenues for this care.

Plus, some of those skilled professionals may not want to work in rural areas.

Payment structures further disadvantage rural providers. Insurance reimbursements for births are already low. In rural areas with higher rates of people relying on Medicaid coverage, which doesn’t pay hospitals as much as insurance, the money recouped can be even lower.

Now, Republican leaders in Washington are proposing major cuts to Medicaid, putting rural hospitals even further out in the cold. In North Carolina, 37% of births are covered by Medicaid, according to KFF.

Larger hospitals can offset these expenses through higher-level neonatal intensive care units, which generate more revenue — an option unavailable to most small rural facilities.

CPP data analysis showed that smaller labor and delivery units — those with less than six birthing rooms — were more vulnerable to complete closure in North Carolina than larger ones between 2013 and 2023. Those rural hospitals just don’t have access to the economies of scale that suburban or urban ones do. Their books are harder to balance.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1742274834093’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’300px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’1200px’;vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’252px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=’927px’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth=’300px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’1200px’;vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’252px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=’927px’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’727px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

This map shows the level of labor and delivery services at hospitals in North Carolina by county, also noting counties with no hospitals and counties where the level of service has changed over the last decade. The map is based on Carolina Public Press analysis of hospital licensing records submitted to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and obtained by CPP through a public records request. Graphic by Mariano Santillan / Carolina Public Press

“Rural hospitals operate with razor-thin margins and sometimes in the red; even small increases in costs can be hard for them to bear,” said Michelle Mello, professor of law at Stanford University, who focuses on the impact of law and regulation on health care delivery and outcomes.

When a major hospital system buys out a rural hospital, it tends to centralize maternity services at an urban hub, CPP analysis showed. But that can take years, with lapses in service in between. Those larger facilities can stomach the losses associated with maternity and treat higher-risk births, which bring in more money.

So why not walk away from servicing the rural communities with low birth rates and centralize services at an urban hub? It seems sound from a business viewpoint.

But consider the perspective of a woman with a high-risk pregnancy who may have to travel across several county lines or a state line to meet with an OB/GYN or to give birth at a labor and delivery center. Then add narrow winding roads in extreme weather at night through mountains or swamps to the mix. That’s the reality for women in some parts of North Carolina.

When maternity services disappear from rural communities, the impact goes beyond dollars and cents. Aside from the transportation logistics that can leave some women in dangerous birth scenarios, there’s an emotional component as well.

“Rural hospitals are so important because mothers might trust them more than they might at a bigger place that they maybe haven’t been, where they just go to deliver,” said Sarah Verbiest, executive director of the Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health at UNC School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

“That’s the beauty of small, rural communities: those trusting relationships.”

Plus, residing in a rural community can create vulnerability to health issues that may cause dangerous circumstances for North Carolina women giving birth.

“Access is definitely a factor, but the other factor too is just looking at chronic illness,” Patricia Cambell, director of North Carolina initiatives at March of Dimes, told CPP.

“When someone in rural areas has limited health care in general, they may have chronic hypertension or diabetes that aren’t getting taken care of — and that’s going to impact outcomes.”

This creates a worrisome cycle. The communities most vulnerable to poor maternal outcomes are often the same ones losing access to care due to financial pressures that seem difficult to resolve within the current hospital care model.

Rural hospitals face workforce exodus

Who is there to care for women in rural areas?

Rural hospitals often have difficulty attracting and retaining birthing specialists, offering them competitive salaries, and providing the resources and experiences necessary for them to train and sharpen their skills.

“Is the workforce willing to be located in rural communities?” asked Belinda Pettiford, chief of the Women, Infant, and Community Wellness Section of the Division of Public Health at DHHS.

“The numbers of patients (whom) rural providers see will be smaller. You went to school to be a provider, you want to use your skills to actually provide these services in rural communities. Will you use all of your skills that you were hoping you would use if patient volume is so low?”

For specialists who have spent years mastering complex procedures, practicing where they might only attend a handful of births monthly can feel professionally unfulfilling — or even unsafe.

Obstetrics and gynecology providers are found liable for negligent care more frequently than nearly any other kind of medical provider, according to the American Medical Association. In the US, 62% of OB/GYNs have faced a lawsuit claiming negligent care at some point in their career.

Fear of these expensive lawsuits may be another factor driving rural hospitals to abandon or reduce labor and delivery services, especially if nurses and doctors don’t get a lot of practice.

Schools like East Carolina University are training leagues of young people who plan to join the labor and delivery workforce. Many of them actually want to return to the small towns they’re from to practice, but not enough jobs may exist for them in that region, according to Rebecca Bagley, director of the nurse-midwifery education program at ECU.

Even if the jobs for these health care workers exist in those smaller communities, the salaries may be lower than for similar roles in North Carolina’s larger cities.

Plus, the premier medical education in the state is located in the state’s urban areas, including UNC-Chapel Hill, Duke University, Wake Forest University, and ECU. The only medical school in a rural area is Campbell University in Lillington.

Providing labor and delivery services in rural areas, where there may not be many other staff to relieve you of your responsibilities, is a different ballgame. Burnout can happen fast.

“It’s a terrible hardship on the providers themselves,” said Kelly Welsh, deputy health director of App Health Care. “They’ve got to be at the hospital 24 hours. A baby could come at any minute.”

If nurses or doctors aren’t getting paid as adequately, fewer babies are actually being born in their care and they have few colleagues to support or relieve them, they may start to look for jobs elsewhere.

With a smaller workforce comes less access to care for patients.

“When you just find out you’re pregnant — maybe you’re five weeks in — and you’re all excited about it, it’s so discouraging when you call the practice and they say, ‘Great, we’ll get you in in three months,’” Bagley said.

“Usually, it’s a really good idea to see a provider sooner than that, and plus, you may not ever end up going to that appointment.”

But as the population ages and declines, fewer rural women are getting pregnant.

In 56 of North Carolina’s 100 counties, adults 65 and older accounted for 20% or more of the population in 2020, according to the Office of State Budget and Management. In 2010, this was true of only 15 counties.

In only 15 counties does the population of people under 17 exceed the population of those above 60, according to DHHS. And this group of counties is expected to shrink.

Transylvania County public health officials see their older population as one reason why maternal health falls by the wayside. Their hospital cut labor and delivery services in 2017. “Transylvania County is older than average,” said Tara Rybka, spokesperson for the Transylvania County health department.

“We are one of the oldest counties in the state. Folks may just not be in that stage of life where they’re looking for prenatal care, or even aware that it exists.”

But these pressures don’t fate small town and rural hospitals to reduce OB/GYN and labor and delivery care.

Some rural hospitals in North Carolina have held the line or even expanded services or capacity: Harris Regional Hospital in Sylva or UNC-Health Chatham in Siler City, for example. It isn’t impossible for small, rural hospitals to allocate more resources towards women’s health.

While some hospitals have decided it’s good public service, brand building or just the right move to keep services in place or expand them at rural facilities, others face real pressures.

But rural hospitals are expected to care for all residents, even if their counties have diminishing populations of women of childbearing age or shrinking pools of health care professionals willing to work there. And if the shots are being called at a system headquarters far away from the individual county, community and patient concerns may not stack up well against the bottom line. These hospital groups face little incentive to make this work unless someone compels them.

So who is holding them accountable?

Well, that’s the problem: no one.

Lack of regulation and accountability

North Carolina does have standards for the levels of neonatal care each hospital is expected to provide, so the Division of Health Service Regulation has some power to enforce those, according to Pettiford. But there are no analogous standards for maternal care. The Division of Health Service Regulation, or DHSR, is housed with DHHS.

DHHS collects data from hospitals on how many delivery rooms each hospital currently has in annual License Renewal Applications, but the agency offers no standardized guidelines on how to count rooms, resulting in wide discrepancies in what the hospitals are actually reporting.

Do hospitals count only the ones in regular use, or all available rooms? What about rooms that are within units but are primarily used for other procedures or purposes, like medical storage or bathrooms?

This inconsistent and indirect system is the only one in place for DHHS to track the number of labor and delivery rooms across the state.

And the department is not actually using the information it gathers to track them.

The department does not generate a report from these license applications, which remain in the form of scanned forms filled out by hand. Nor does DHHS analyze changes in the reported numbers over time. CPP obtained the applications from DHHS and analyzed the shifts in service independently through a records request.

“DHSR doesn’t have reports with that data,” the agency replied when CPP initially asked for data on changes in maternity offerings over time.

Though DHHS regulates how many labor and delivery rooms a given hospital is allowed to have based on the health care needs of the region through the Certificate of Need process, the department does not check back to see whether the hospital is actually meeting that need.

When changes in hospital offerings go unnoticed by DHHS, the agency has no way to enforce the maintenance of a certain level of care. DHHS is not bound by any legal requirement to do so.

This results in a distinct lack of regulatory or legal incentive for hospitals to maintain the same number of delivery rooms year over year.

Locally, little accountability exists for hospitals. County health departments create and share reports on community health needs, and occasionally work with hospitals in an attempt to meet them, but they have no power over hospital executive’s actual decision making.

“We certainly, if we see changes in services that would impact public health, we would speak up about that,” said Jennifer Greene, health director at AppHealthCare, which serves Alleghany, Ashe and Watauga counties.

“I don’t know how much power we would have. Are we at their whim? I think generally.”

This lack of accountability makes cutting maternity services almost easy for North Carolina hospitals — perhaps not from a patient-centered perspective, but certainly where paperwork, potential lawsuits and a wide range of costs are concerned.

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The post Rural hospitals in NC face pressures to cut women’s services appeared first on carolinapublicpress.org

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

White House officials hold prayer vigil for Charlie Kirk

SUMMARY: Republican lawmakers, conservative leaders, and Trump administration officials held a prayer vigil and memorial at the Kennedy Center honoring slain activist Charlie Kirk, founder of Turning Point USA. Kirk was killed in Utah, where memorials continue at Utah Valley University and Turning Point USA’s headquarters. Police say 22-year-old Tyler Robinson turned himself in but has not confessed or cooperated. Robinson’s roommate, his boyfriend who is transitioning, is cooperating with authorities. Investigators are examining messages Robinson allegedly sent on Discord joking about the shooting. Robinson faces charges including aggravated murder, obstruction of justice, and felony firearm discharge.

White House officials and Republican lawmakers gathered at the Kennedy Center at 6 p.m. to hold a prayer vigil in remembrance of conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

https://abc11.com/us-world/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Family, friends hold candlelight vigil in honor of Giovanni Pelletier

SUMMARY: Family and friends held a candlelight vigil in Apex to honor Giovanni Pelletier, a Fuquay Varina High School graduate whose body was found last month in a Florida retention pond. Giovanni went missing while visiting family, after reportedly acting erratically and leaving his cousins’ car. Loved ones remembered his infectious smile, laughter, and loyal friendship, expressing how deeply he impacted their lives. His mother shared the family’s ongoing grief and search for answers as authorities continue investigating his death. Despite the sadness, the community’s support has provided comfort. A celebration of life mass is planned in Apex to further commemorate Giovanni’s memory.

“It’s good to know how loved someone is in their community.”

More: https://abc11.com/post/giovanni-pelletier-family-friends-hold-candlelight-vigil-honor-wake-teen-found-dead-florida/17811995/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

NC Courage wins 2-1 against Angel City FC

SUMMARY: The North Carolina Courage defeated Angel City FC 2-1 in Cary, ending their unbeaten streak. Monaca scored early at the 6th minute, followed by Bull City native Brianna Pinto’s goal at the 18th minute, securing a 2-0 halftime lead. Angel City intensified in the second half, scoring in the 88th minute, but the Courage held firm defensively to claim victory. Pinto expressed pride in the win, emphasizing the team’s unity and playoff ambitions. Nearly 8,000 fans attended. Coverage continues tonight at 11, alongside college football updates, including the Tar Heels vs. Richmond game live from Chapel Hill.

Saturday’s win was crucial for the Courage as the regular season starts to wind down.

https://abc11.com/post/north-carolina-courage-wins-2-1-angel-city-fc/17810234/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

What we know about Charlie Kirk shooting suspect, how he was caught

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Federal hate crime charge sought in Charlotte stabbing | North Carolina

-

Our Mississippi Home5 days ago

Screech Owls – Small but Cute

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

NW Arkansas Championship expected to bring money to Rogers

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Huntsville Fire & Rescue Holds 9/11 Memorial Service | Sept. 11, 2025 | News 19 at 5 p.m.

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Under pressure, some immigrants are leaving American dreams behind

-

Mississippi News Video6 days ago

Mississippi Science Fest showcases STEAM events, activities

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

What to know about Trump’s National Guard deployment to Memphis