News from the South - Texas News Feed

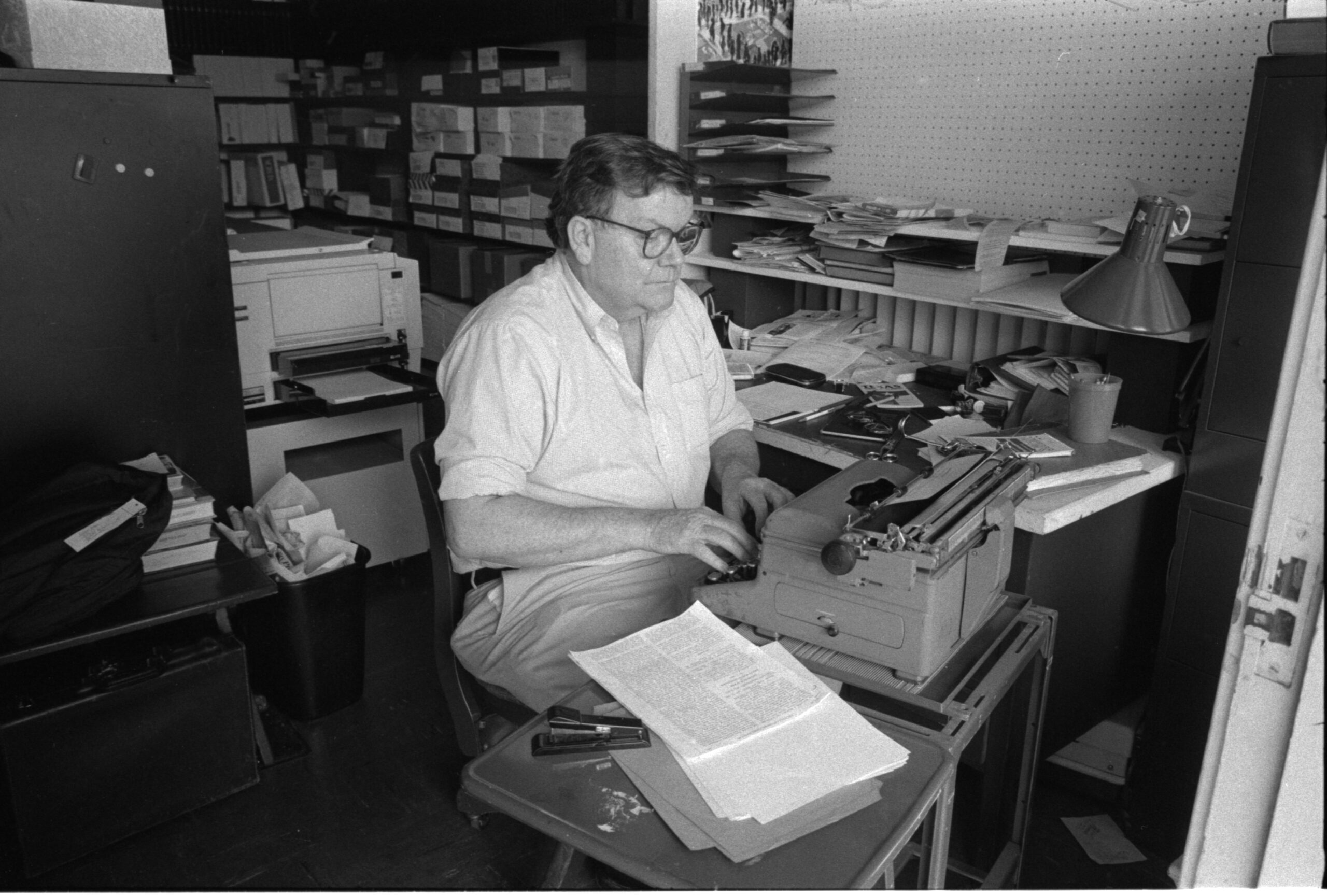

Ronnie Dugger, 1930-2025

Ronnie Dugger, founding editor and longtime publisher of the Texas Observer and for many years the crusading conscience of the progressive movement in Texas and beyond, died of complications of dementia at an assisted living facility in Austin on May 27. He was 95.

Dugger was the author of biographies of Lyndon B. Johnson and Ronald Reagan and other significant books, as well as countless articles and essays about Texas politics, civil rights, higher education, capital punishment, nuclear proliferation, and computerized voting, among many issues that attracted his earnest attention over the years. He also wrote poetry. His wide range of interests notwithstanding, he will always be associated with the scrappy little Austin-based political journal created in his image.

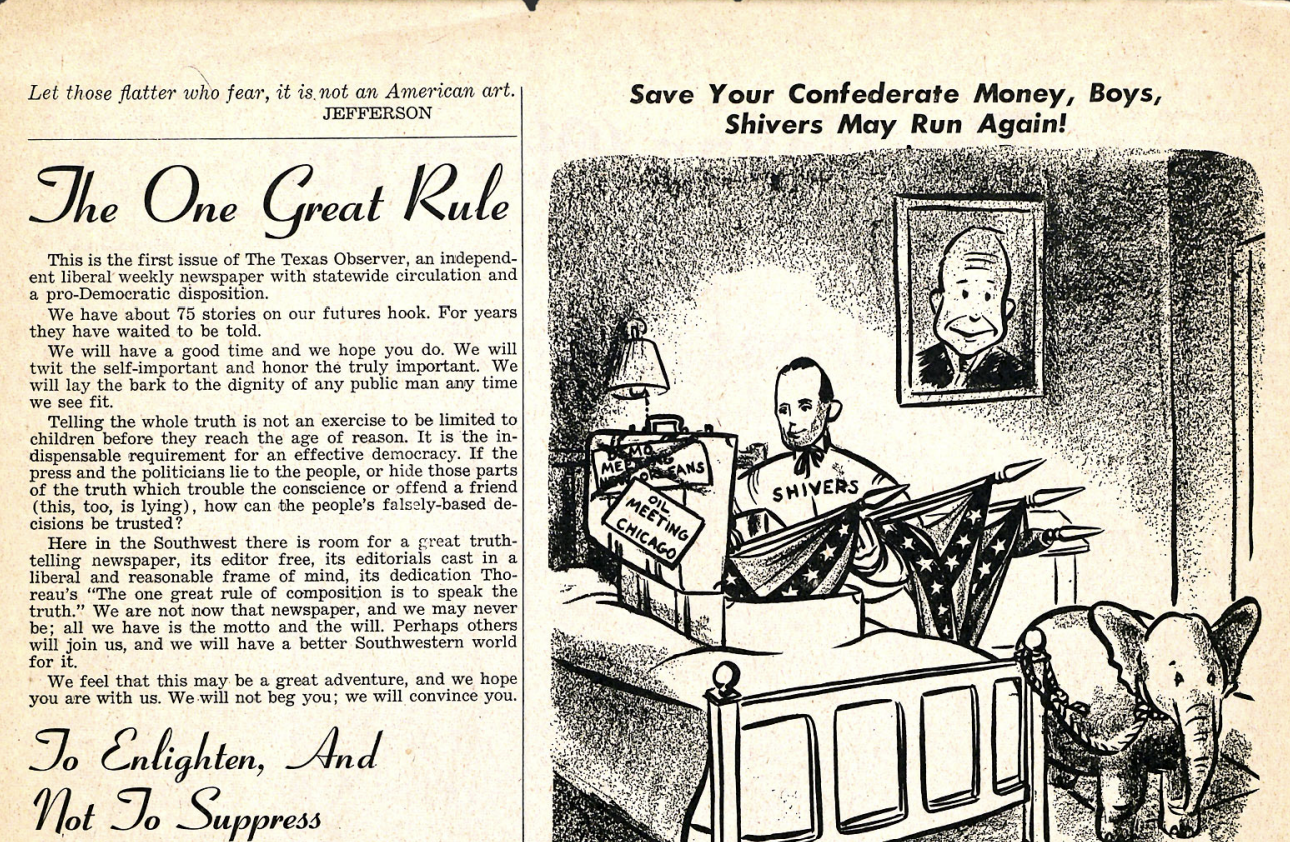

Few would have predicted his shaping influence when the Observer came into being in late 1954. Dugger himself would have been among the skeptics.

Twenty-four years old at the time and a recent graduate of UT-Austin, where he served as an outspoken liberal editor of The Daily Texan, he had charted a different course for himself. On a Saturday in October, he was packing his car to leave Austin, with plans to embark the following Monday on a quintessential young man’s adventure. He would drive to Corpus Christi, catch on with a shrimp boat and then jump ship in Mexico. He would head back to Texas in the company of migrant laborers and farmworkers. Perhaps he would write a novel.

A phone call interrupted his adventure before it began. The call would evolve into a life’s calling.

Some 150 Texas liberals—“usually self-identified,” as Dugger recalled in later years, “as loyal Democrats who were pledged to support the then liberal Democratic nominees”—were meeting at the Driskill Hotel in downtown Austin on that Saturday. They had agreed to spend $5,000 to purchase a weekly newsletter published by Paul Holcomb, a lay Church of Christ preacher who admired William Jennings Bryan and FDR. The State Observer would become The Texas Observer; it would be the party organ of Texas progressives. Needing an editor, a member of the group called Dugger, wondering if the former Daily Texan editor would be interested.

He was interested enough to drive downtown for lunch in the hotel restaurant with a few of the group. Principled and high-minded almost to a fault—as his future cohorts would soon learn—he explained that he was a Democrat but considered himself independent. He had no interest in working for a party organ, he said, “but that if they would give me ‘exclusive control of the editorial content,’ I would take the job.”

They “caucused and fumed,” Dugger recalled, but then, to his surprise, said yes. “As the editor I would have exclusive control of all of the paper’s editorial content. As the publisher they would have the absolute right to fire me anytime they wanted to.”

Those beleaguered Texas liberals—among them East Texas lumber heiress Frankie Randolph (“the Eleanor Roosevelt of Texas”), Madisonville oilman J.R. Parten, liberal banker Walter Hall of Dickinson, and future Congressman Bob Eckhardt—not only waylaid a young man’s Yucatan adventure, but they also changed his life. For nearly three-quarters of a century, he would dedicate himself to changing Texas, if not the world. He would become, in the words of Willie Morris, his friend and successor as Observer editor, “one of the great reporters of our time.”

“When we began,” Dugger wrote in an essay entitled “Journalism for Justice,” “there was a silence in Texas about racism, poverty and corporate power. As Ralph Yarborough never let us forget, we ranked dead last among the major states and next-to-last in the South in education, health care and programs for the poor. … We were Texas, a backwater braggish and bigoted and brutal, slow and rich and poor.”

The state’s daily newspapers at the time were flaccid. They were, in the words of Larry L. King, “slavishly adoring of the reigning powers.” Dugger hearkened back to a more bracing tradition reflected in the populist protest journalism of the late-19th century, the fearlessness of William Cowper Brann’s Waco-based Iconoclast and the plain-spoken honesty of Holcomb’s State Observer. Dugger and the state’s small band of liberals also found allies in the labor movement, with its roots in the New Deal. Yarborough was their champion.

As Morris noted in his classic North Toward Home, Dugger “began writing about what actually happened.” With associate editors Billy Lee Brammer (author in years to come of the renowned political novel, The Gay Place), with Lawrence Goodwyn and Robert Sherrill and an informal roster of contributors that included J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb, the young editor opened up for Observer readers “the operations of the state Legislature, the courage and disarray of a pathetically small political opposition in the state, the effect on Texas’ culture of highly organized know-nothing groups working on civic clubs, school boards and high school government classes.”

When the Legislature left town, Dugger left too. He slid behind the wheel of his battered ’48 Chevy and hit the Texas backroads, the car packed, as Morris remembered, with a jumble of camping equipment, six-packs of beer, cans of sardines, galley proofs, and old loaves of bread. When the ill-treated Chevy—Dugger called it “the Green Hornet”—broke down in some little town, as it inevitably did, Dugger would stick around until he could get it fixed, meanwhile talking to local folks, scribbling notes, and coming to understand the beguiling, confounding Lone Star State. Often, he was getting out the fortnightly journal—“fortnightly” was a Dugger word, Observer editor Kaye Northcott noted—pretty much by himself.

“One afternoon,” Morris recalled, “Dugger telephoned me from a small town in East Texas. ‘Something radical’s happened,’ he said. ‘The motor fell out.’ That car was an indispensable contribution to Dugger’s understanding of Texas.”

Dugger was earnest, indefatigable, almost manic in those days. “One week, early on,” King recalled in his book In Search of Willie Morris, “he actually worked 120 hours; he drove all over Texas, goading, questioning, preaching, writing ‘red hot’ stories and smash-mouth editorials, trying to sell Texas Observer subscriptions – his goal was 10,000 subscribers rather than the 6,000 he had – and hoping to awaken the masses to how shoddily they were being served by most of their alleged representatives.”

It was a quixotic quest, to be sure, but as King also acknowledged, “I seriously doubt whether the paper would have lasted out its first year without Ronnie, without his total commitment, all his resources and his crackling nervous vitality.”

He was born Ronald Edward Dugger in Chicago on April 16, 1930, to William LeRoy Dugger of San Antonio and Mary King Dugger, a native of Glasgow, Scotland, who was known as Dolly.

According to family lore, Dolly had left Scotland when her mother refused to allow her to go to college. Also according to family lore, Dolly and LeRoy met in a Galveston boarding house, in a room where residents had huddled together to ride out a hurricane. LeRoy had considered becoming a priest but fell for Dolly instead (again, family lore). A lifelong Republican until Watergate, he worked as a bookkeeper, she as a salesperson in a San Antonio department store.

Their son graduated from San Antonio’s Brackenridge High School and received his undergraduate degree with high honors from the University of Texas at Austin in 1950. He also did graduate work in economics and philosophy at UT and political theory and economics at Merton College, Oxford, in 1951-52.

He had been born, Dugger recalled, “into a devout, hard-working Catholic family in San Antonio, raised believing in good and bad. Our rented first-floor of a house in the King William district at 302 Washington Street was across the street from the San Antonio River, beyond which the Mexicans lived on their vast West Side, acres and acres of poverty, misery and the other kinds of violence.”

He was a loner as a child, a voracious reader. In high school he was “ethically impressed” by the novels of Charles Dickens and by Marx’s labor theory of value. “At UT,” he recalled, “I imbibed the values of the public good which prevailed in the Veblenian school of economics called institutionalism, which was then dominant there. ”

Dugger always remembered what he called “the decisive ethical event of my life.” In a Mexican border town, he happened to notice a little boy in ragged clothes standing on a street corner. Their eyes met, and Dugger realized that “to him I was a rich American, and I felt deeply for him.”

Back in Austin, he recalled listening “as demagogues berated every attempt to favor the poor in legislation as socialist or communist and realizing that business bribery was the Legislature’s way of life. I understood that my state had been corrupted by the major corporations and that the daily newspapers, silent or abusive about almost everything that mattered, were a part of that corruption.”

Regarding power, he conceded his innocence. “Probably because the Catholics had convinced me to believe, by deductive implication, in the power of virtue, when I started putting out the Observer I thought that if you just showed people wrong they would make it right.”

He came to realize that he himself was wrong. “In a democracy that works,” he wrote in 2004, “the truth should do it, but during my eight years’ reporting on the Observer I had my first close encounter with the radical fact, still leering brutally at us all, that democracy the way we have and practice it does not produce sufficient justice.”

The chastened young idealist did not give up, but after eight years he gave out. He hired Morris as associate editor, stayed around for a few months and then headed for the hills with, as Morris recalled, “everything Thoreau ever wrote.”

Morris was the first in a succession of young and often inexperienced colleagues who shared Dugger’s dedication to fair and accurate reporting, his reverence for the written word, his fascination (and frustration) with Texas. “He taught those of us who passed through the Observer en route to our more personal work how to view public life as an ethical process, how to be fair,” Morris wrote in North Toward Home.

Morris left the Observer after two years to become the youngest editor in the history of the venerable Harper’s magazine. He was arguably the best known of the Observer editors—until Dugger, looking for a second editor in 1968 to help associate editor Northcott, found a young Houston native whose brash Hello Dolly personality and irrepressible sense of humor would leaven the earnestness of the liberal publication (and, to some extent, its founding editor).

“Everybody applied, because there was nothing else in Texas except daily newspapers,” Northcott recalled. Most of the applicants, she said, were young men, except for a rookie reporter at the Minneapolis Herald-Tribune. Her name was Molly Ivins.

“We made the bold step of flying her down from Minnesota, and we had no money,” Northcott said. “But anyway, we got Molly down here, and she stood out because of her humor. Neither of us found anything odd about the fact that she brought a six-pack for lunch. Just for her.”

Northcott became editor and Ivins co-editor—Northcott as Ms. Inside, Ivins as Ms. Outside. While Northcott was in the office taking care of production chores, Ivins would be prowling the Capitol, kibitzing and cracking jokes, scribbling notes in the women’s restroom about the daily circus unfolding under the pink dome and hanging out later in the day with lawmakers, lobbyists, and fellow reporters at Scholz Garten.

Such is the legend, although Northcott says she “was out and about too.” She laughs. “In fact, every funny thing I ever wrote has been attributed to Molly. We wrote a whole lot together.”

Ivins also helped with production chores, including staying up all night with editorial assistant John Ferguson to make sure the issue was in the printer’s hands by the time the sun came up. Northcott and Ivins worked together amicably. Both also learned from their boss, the consummate reporter. They appreciated the fact that he had hired two young feminists to run the Observer.

Dugger, who debated the erudite William F. Buckley over Vietnam during an appearance at UT, was a serious man. Northcott recalled that he read the Roman historian Livy over breakfast. Still, he was able to appreciate Ivins’ humor.

“As she got funnier and funnier I enjoyed it like everybody else,” he told Ivins biographers Bill Minutaglio and W. Michael Smith. “She was like Will Rogers but in an entirely new way, in that she was as vulgar as a stevedore’s daughter.”

Some things irritated him, though, including the fact that Ivins and Northcott brought their dogs to the office. “I had given her this dog,” Northcott recalled. “It was a puppy, the last of the litter, and it had a little glob of shit on its forehead, so I called it Shit as a way to tell it from the other little black puppies. Of course, Molly called it that, and Ronnie disapproved of that.”

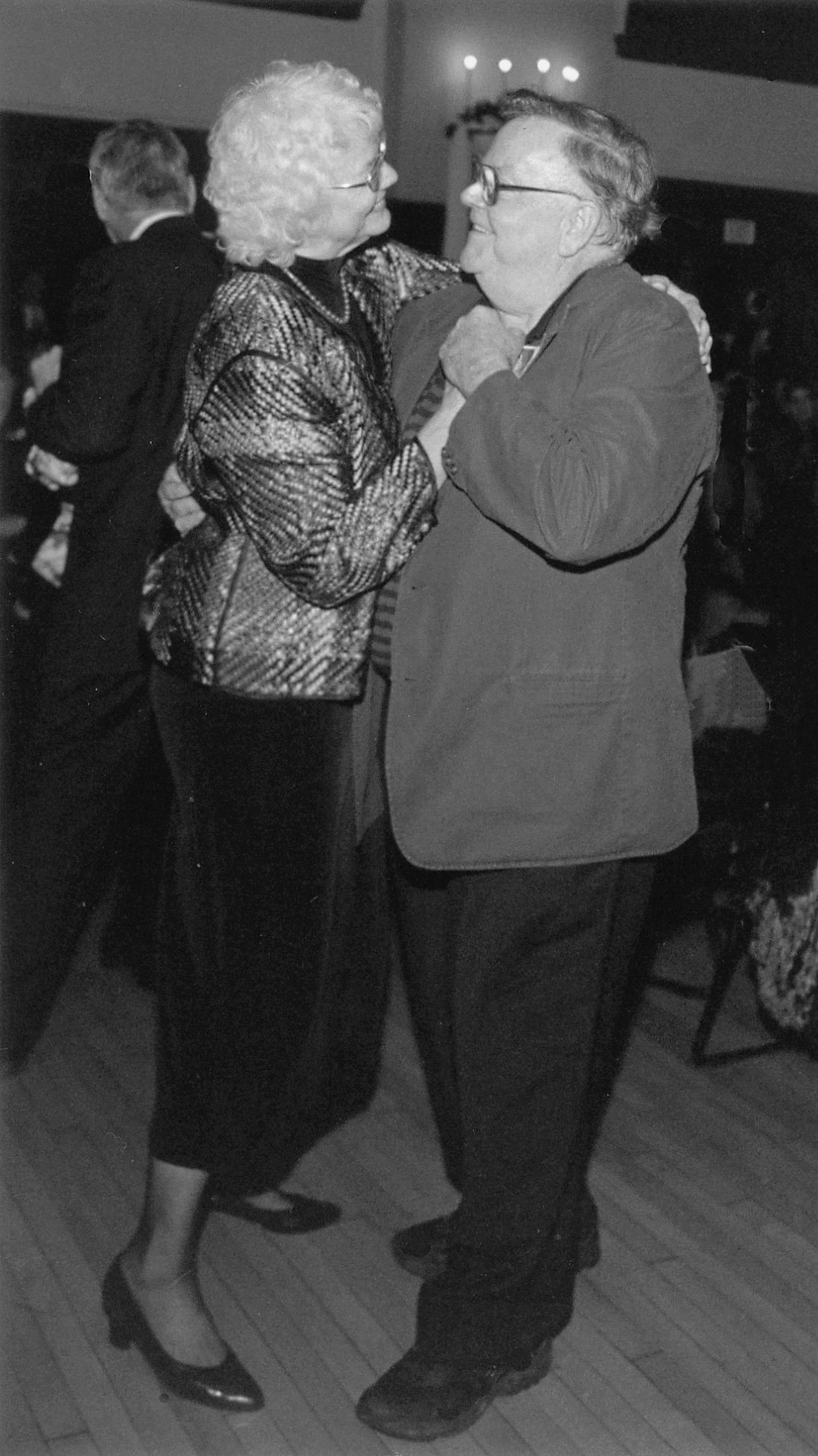

That sense of propriety would become a source of friendly contention between Dugger and his close friend Bernard Rapoport, the wealthy Waco insurance magnate who, in the early 1960s, succeeded Frankie Randolph as the Observer’s primary benefactor.

Rapoport’s clients were labor unions. “That was the commonality that Dugger and Rapoport had,” said Don Carleton, executive director of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at UT-Austin. “The bridge was labor.”

“Ronnie is more of a purist, and I am more of a pragmatist,” Rapoport wrote in his memoir, Being Rapoport: Capitalist with a Conscience. “Unfortunately, I think he is committed to being too pure, and that does seem to make him appear to be a little bit phony. He really isn’t phony personally. … But he desperately wants to be pure, and he wants to set the standards for that purity. That gets him into trouble once in a while. He and I fight about that, because I know I’m not pure and I know he’s not pure; the difference is, I don’t want to act like I am.”

However pure he was ideologically, the student of Livy also could be a bit Machiavellian. In a special election in 1961, the Observer endorsed Republican John Tower for the U.S. Senate seat that LBJ had to relinquish when he became vice president. In an effort “to free their party from the dead weight of the Dixiecrats,” Dugger urged liberals to oppose the conservative Democrat, William Blakely, who had been appointed as interim senator by Governor Price Daniel.

Dugger contended that “Dollar Bill” Blakely was no Democrat at all but “a cynical millionaire racist.” A good Democrat could beat him when he ran for a full six-year term. As Larry King wryly noted, the state’s “kamikaze liberals,” including Dugger, “miscalculated by almost thirty years.”

With the Observer in dependable hands (if not paws) by the mid-’60s, Dugger began to look beyond Texas politics. His first book, Dark Star, Hiroshima Reconsidered in the Life of Claude Eatherly of Lincoln Park, Texas, published in 1966, was his initial foray into nuclear war, an issue that would become a lifelong concern. Eatherly was the reconnaissance pilot who on August 6, 1945, ordered the message sent to the plane carrying the atom bomb that weather conditions made Hiroshima a suitable target.

“[Dugger] tells in detail the story of a Texas boyhood, of his life as an Army flier, and of a bizarre adventure in gun-running after the war; he makes plausible, even inevitable, Eatherly’s eventual confusion, loss of identity and torment,” sociologist John Thompson wrote in a positive review in The New York Review of Books.

Decades later, Dugger was still ruminating about nuclear war. “I don’t think most of the American people have any idea where we are, ethically, with nuclear weapons,” he told Brad Buchholz of the Austin American-Statesman in 2012. “If we don’t deal with this, it’s going to kill us all.”

For his second book, Our Invaded Universities, Dugger returned to Texas politics. As Daily Texan editors, both he and Morris regularly went to war editorially against the governor and the Legislature, who felt compelled to meddle in the affairs of the sprawling academic institution a couple of blocks north of the Capitol. Shortly before Dugger’s arrival at UT, the aggressively conservative board of regents had fired UT President Homer Rainey, primarily on ideological grounds.

“Texas itself, its chronic xenophobia fed by the passions of the McCarthy period, was not an entirely pleasant place in those years,” Morris wrote in North Toward Home. “There was venom in its politics and a smugness in its attitude to outsiders and to itself.”

Two decades later, with politicians still meddling, Dugger resolved “to stroll into the haughty facades the universities put up.” By focusing primarily on his alma mater, he explored how America’s academic institutions have been “invaded” by politics and big business, thereby undermining the rationale and purpose of “the most important institution in Western civilization.” He offered proposals “that might help restore – or perhaps the word is provide – the vigor and balance, independence and humane values, freedom from fear of ideas and enjoyment of debate and freedom that higher education must give us or fail us.”

UT was important to Dugger for many reasons, including the fact that he met Jean Williams on campus. Both 21 when they married in 1951, Ronnie and Jean Dugger stayed married until 1976.

In 1982, Dugger married Patricia Blake, an associate editor of Time magazine, and moved to Wellfleet, Massachussetts, New York City, and later Wellesley, Massachussetts. His publisher, W.W. Norton, was clamoring at the time for his long-overdue biography of Lyndon Johnson. (The first volume of Robert Caro’s multi-volume biography of LBJ had just appeared, adding to Norton’s urgency.)

Dugger had interviewed Johnson at his Hill Country ranch in 1955. The state’s senior U.S. senator was the new majority leader and, in Dugger’s words, “hell-bent on the presidency.” As he would write in The Politician, Johnson was “rude, intelligent, shrewd, charming, compassionate, vindictive. Maudlin, selfish, passionate, volcanic and cold, vicious and generous.”

At the ranch, the two of them sitting beside the pool on plastic chaise longues, Johnson proposed helping the Observer increase its circulation tenfold by transforming it into “not a party organ, but a Johnson pipe organ that his nod could cause to bellow forth with Wagnerian splendor.” Dugger considered the offer a bribe.

Dugger interviewed Johnson several times in the White House for his biography, including one evening in the family dining room in December 1967. Dugger asked him about nuclear weapons and a president’s responsibility for deciding whether to use them. Johnson exploded.

In Dugger’s words, “his gorge rose now against me and my question, against the dissenters, the criticizers, the kibitzers who have none of the burden, none of the inside knowledge and none of the responsibility. ”

Dugger continued: “Pushed completely back from the table now, glowering at me with his inescapable power for mass nuclear killing fresh in his being and his feelings, he exclaimed that he is the one who has to decide whether to bomb, he is the one who has to decide whether to send in troops – he shouted at me with a terrible intensity, jamming his thumb down on an imaginary spot in the air beside him, ‘I’m the one who has to mash the button!’”

Johnson continued meeting with Dugger, even though Dugger was passionate and very public about his opposition to the Vietnam War. Their final conversation took place on March 23, 1968. A week later LBJ announced he would not seek a second term.

Johnson always seemed intrigued by the man who could not be bought. As former LBJ aide Bill Moyers once observed, Johnson “loathed what Ronnie wrote about him because it was so on target.” Moyers thought he was fascinated by Dugger.

Fascinated or not, LBJ couldn’t resist a bizarre insult. “If you investigate that boy’s bloodline,” he growled to a staffer, “you’ll find a dwarf in there somewhere.”

Dugger’s LBJ biography came out in 1982. He continued writing for The Nation, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and other publications and in 2011 received the prestigious George Polk Career Award.

After Patricia Blake’s death in 2010, Dugger moved back to Austin, where he lived alone in a small house not far from the university. “He was very happy to be back in Texas,” recalled daughter Celia, a longtime New York Times reporter and editor. “It’s home, and he felt that in his bones. People here knew him, and admired him, and remembered the contributions he’d made to the state. And that meant a great deal to him.”

In addition to his daughter and her husband, Barry Bearak, of Pelham, New York, survivors include his son, Gary Dugger, of Carmel, California, and six grandchildren.

As much as he was happy to be back home, Dugger was appalled by the grudging retreat of progressive politics and ideals in the face of hard-right Republican advances and then near-total dominance. “What happened?” he would ask Northcott, who almost felt guilty because she had stayed in Texas and had been unable to stop the slide into retrogression.

Although writing poems, hundreds of them, was perhaps a distraction, he was still the journalist. His mission was to thwart Donald Trump in any way he could, throughout his first term and then as he launched his campaign for a second. Until near the end, Celia Dugger said, her father remained passionate about the failure of this nation and the world to do anything substantive to avert nuclear war.

At press time, the Observer—which without Ronnie Dugger would never have become the independent muckraker it did—is still going strong at 71 years old.

The post Ronnie Dugger, 1930-2025 appeared first on www.texasobserver.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Left-Leaning

This content reflects a left-leaning political perspective. It highlights the life and work of Ronnie Dugger, a figure closely associated with progressive and liberal causes in Texas, emphasizing his commitment to civil rights, social justice, and opposition to corporate influence. The article praises Dugger’s dedication to exposing corruption, advocating for the underprivileged, and valuing independent and critical journalism aligned with progressive ideals. The tone is respectful and admiring of Dugger’s liberal contributions, while critical of conservative or reactionary forces in Texas politics and governance.

News from the South - Texas News Feed

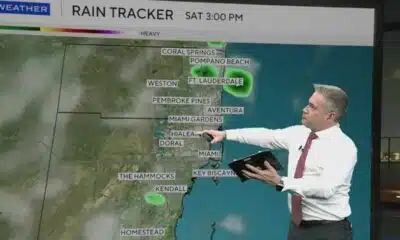

La Niña now expected to last all winter

SUMMARY: For the first time this year, La Niña is now forecast to last throughout the entire winter, with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center giving it a 54% chance for December-February. Previously, ENSO Neutral was favored for winter. La Niña occurs when sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific are 0.5ºC below average, typically pushing the Pacific Jet Stream north, causing drier, warmer conditions in the southern U.S. and wetter areas in the Pacific Northwest. Last winter, a weak La Niña brought a record warm December but cooler January-February, below-average rainfall, snow in Austin, and more freezes than normal. Another mild La Niña winter is expected for Central Texas.

The post La Niña now expected to last all winter appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Texas high school football scores for Friday, Sept. 12

SUMMARY: Lake Travis dominated Midland Legacy 59-13 in a spirited farewell to the old Cavalier Stadium before renovations force home games to move to Dripping Springs High School. Across Central Texas, notable district wins included Anderson over College Station (37-14), Bowie against Glenn (38-14), and Dripping Springs edging Harker Heights (31-26). High-scoring games saw McNeil top Westwood 70-45, and Hutto defeat Cedar Ridge 63-49. Close contests included Vista Ridge’s 30-29 win over Round Rock and Austin LBJ’s 34-33 overtime victory against Wimberley. The article also features an extensive list of scores from other Texas high school football games.

The post Texas high school football scores for Friday, Sept. 12 appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Safe Central Texas meet-up spots for online purchases

SUMMARY: The Lockhart Police Department created its first Community MeetUp Spot for safe internet purchase exchanges after a man stole shoes during a transaction. Located in the police station parking lot at 214 Bufkin Lane, it offers a secure, monitored area encouraging buyer and seller safety. Positive community feedback inspired the initiative. Several Central Texas police departments—including Georgetown, Cedar Park, Round Rock, Pflugerville, Manor, Austin, and Kyle—also provide designated or informal safe exchange spots. The Austin Police emphasize researching buyers/sellers, trusting instincts, and following safety tips such as taking photos, noting license plates, meeting in public areas, and keeping personal info private.

The post Safe Central Texas meet-up spots for online purchases appeared first on www.kxan.com

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Reagan era credit pumps billions into North Carolina housing | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Amid opposition to Blount County medical waste facility, a mysterious Facebook page weighs in

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

3 states push to put the Ten Commandments back in school – banking on new guidance at the Supreme Court

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed6 days ago

South Carolina’s Tess Ferm Wins Miss America’s Teen 2026

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

National Grandparents Day (9-7-25) and the special bond shared with their grandchildren

-

Local News6 days ago

Duke University pilot project examining pros and cons of using artificial intelligence in college

-

Local News7 days ago

Marsquakes indicate a solid core for the red planet, just like Earth

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

1587 Prime gives first look at food, cocktail menu ahead of grand opening in KC