Vaccine research quickly picked up to try to prevent a possible flu pandemic in 1976.

Donald S. Burke, University of Pittsburgh

Nineteen-year-old U.S. Army Pvt. David Lewis set out from Fort Dix on a 50-mile hike with his unit on Feb. 5, 1976. On that bitter cold day, he collapsed and died. Autopsy specimens unexpectedly tested positive for an H1N1 swine influenza virus.

Virus disease surveillance at Fort Dix found another 13 cases among recruits who had been hospitalized for respiratory illness. Additional serum antibody testing revealed that over 200 recruits had been infected but not hospitalized with the novel swine H1N1 strain.

Officials worried about a repeat of something like the 1918 flu pandemic, which took hold in soldiers and spread globally.

Alarm bells instantly went off within the epidemiology community: Could Pvt. Lewis’ death from an H1N1 swine flu be a harbinger of another global pandemic like the terrible 1918 H1N1 swine flu pandemic that killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide?

The U.S. government acted quickly. On March 24, 1976, President Gerald Ford announced a plan to “inoculate every man, woman, and child in the United States.” On Oct. 1, 1976, the mass immunization campaign began.

Meanwhile, the initial small outbreak at Fort Dix had rapidly fizzled, with no new cases on the base after February. As Army Col. Frank Top, who headed the Fort Dix virus investigation, later told me, “We had shown pretty clearly that (the virus) didn’t go anywhere but Fort Dix … it disappeared.”

Nonetheless, concerned by that outbreak and witnessing the massive crash vaccine program in the U.S., biomedical scientists worldwide began H1N1 swine influenza vaccine research and development programs in their own countries. Going into the 1976-77 winter season, the world waited – and prepared – for an H1N1 swine influenza pandemic that never came.

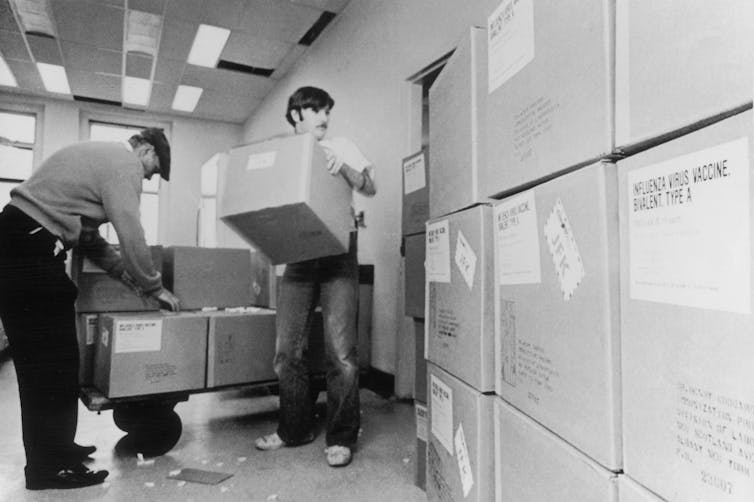

By September 1976, New York State Health Department workers were unloading cartons of swine flu vaccine for distribution.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. As an experienced infectious disease epidemiologist, I make the case that there were unintended consequences of those seemingly prudent but ultimately unnecessary preparations.

What was odd about H1N1 Russian flu pandemic

In an epidemiological twist, a new pandemic influenza virus did emerge, but it was not the anticipated H1N1 swine virus.

In November 1977, health officials in Russia reported that a human – not swine – H1N1 influenza strain had been detected in Moscow. By month’s end, it was reported across the entire USSR and soon throughout the world.

Compared with other influenzas, this pandemic was peculiar. First, the mortality rate was low, about a third that of most influenza strains. Second, only those younger than 26 were regularly attacked. And finally, unlike other newly emerged pandemic influenza viruses in the past, it failed to displace the existing prevalent H3N2 subtype that was that year’s seasonal flu. Instead, the two flu strains – the new H1N1 and the long-standing H3N2 – circulated side by side.

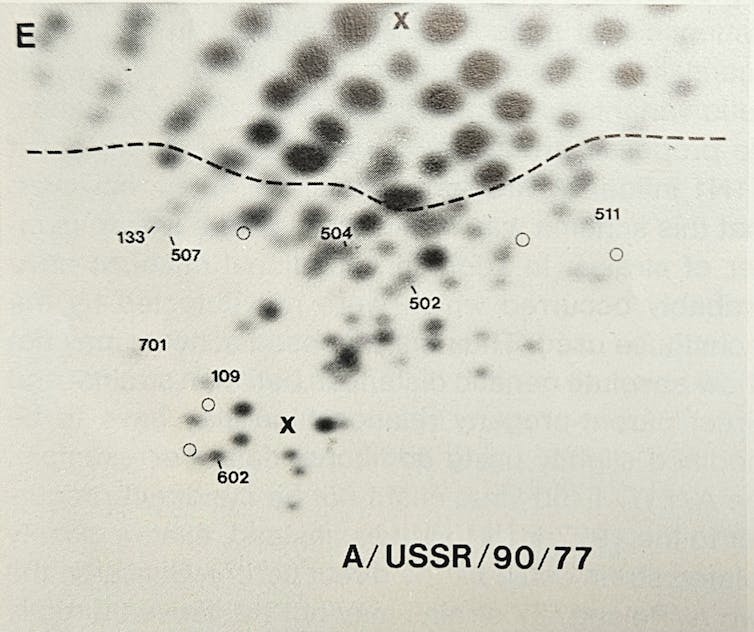

Here the story takes yet another turn. Microbiologist Peter Palese applied what was then a novel technique called RNA oligonucleotide mapping to study the genetic makeup of the new H1N1 Russian flu virus. He and his colleagues grew the virus in the lab, then used RNA-cutting enzymes to chop the viral genome into hundreds of pieces. By spreading the chopped RNA in two dimensions based on size and electrical charge, the RNA fragments created a unique fingerprint-like map of spots.

Researchers were surprised to see the ‘genetic fingerprint’ for the 1977 H1N1 Russian flu strain closely matched that of an extinct influenza virus. Peter Palese

Much to Palese’s surprise, when they compared the spot pattern of the 1977 H1N1 Russian flu with a variety of other influenza viruses, this “new” virus was essentially identical to older human influenza H1N1 strains that had gone extinct in the early 1950s.

So, the 1977 Russian flu virus was actually a strain that had disappeared from the planet a quarter century early, then was somehow resurrected back into circulation. This explained why it attacked only younger people – older people had already been infected and become immune when the virus circulated decades ago in its earlier incarnation.

But how did the older strain come back from extinction?

Though called the Russian flu, the virus appears to have been circulating elsewhere before being identified in the Soviet population.

Refining the timeline of a resurrected virus

Despite its name, the Russian flu probably didn’t really start in Russia. The first published reports of the virus were from Russia, but subsequent reports from China provided evidence that it had first been detected months earlier, in May and June of 1977, in the Chinese port city of Tientsin.

In 2010, scientists used detailed genetic studies of several samples of the 1977 virus to pinpoint the date of their earliest common ancestor. This “molecular clock” data suggested the virus initially infected people a full year earlier, in April or May of 1976.

So, the best evidence is that the 1977 Russian flu actually emerged – or more properly “re-emerged” – in or near Tientsin, China, in the spring of 1976.

A frozen lab virus

Was it simply a coincidence that within months of Pvt. Lewis’ death from H1N1 swine flu, a heretofore extinct H1N1 influenza strain suddenly reentered the human population?

Influenza virologists around the world had for years been using freezers to store influenza virus strains, including some that had gone extinct in the wild. Fears of a new H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 1976 in the United States had prompted a worldwide surge in research on H1N1 viruses and vaccines. An accidental release of one of these stored viruses was certainly possible in any of the countries where H1N1 research was taking place, including China, Russia, the U.S., the U.K. and probably others.

Years after the reemergence, Palese, the microbiologist, reflected on personal conversations he had at the time with Chi-Ming Chu, the leading Chinese expert on influenza. Palese wrote in 2004 that “the introduction of the 1977 H1N1 virus is now thought to be the result of vaccine trials in the Far East involving the challenge of several thousand military recruits with live H1N1 virus.”

Although exactly how such an accidental release may have occurred during a vaccine trial is unknown, there are two leading possibilities. First, scientists could have used the resurrected H1N1 virus as their starting material for development of a live, attenuated H1N1 vaccine. If the virus in the vaccine wasn’t adequately weakened, it could have become transmissible person to person. Another possibility is that researchers used the live, resurrected virus to test the immunity provided by conventional H1N1 vaccines, and it accidentally escaped from the research setting.

Whatever the specific mechanism of the release, the combination of the detailed location and timing of the pandemic’s origins and the stature of Chu and Palese as highly credible sources combine to make a strong case for an accidental release in China as the source of the Russian flu pandemic virus.

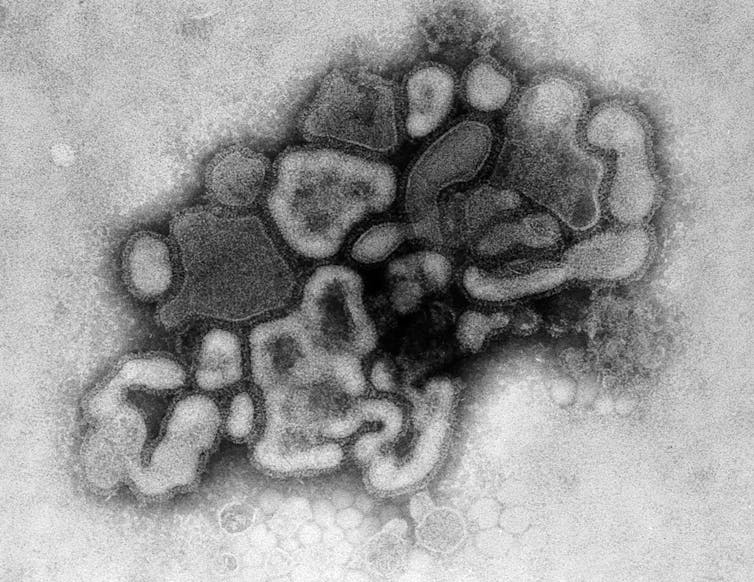

The H1N1 influenza virus identified at Fort Dix wasn’t the one that ended up causing a pandemic.

A sobering history lesson

The resurrection of an extinct but dangerous human-adapted H1N1 virus came about as the world was scrambling to prevent what was perceived to be the imminent emergence of a swine H1N1 influenza pandemic. People were so concerned about the possibility of a new pandemic that they inadvertently caused one. It was a self-fulfilling-prophecy pandemic.

I have no intent to lay blame here; indeed, my main point is that in the epidemiological fog of the moment in 1976, with anxiety mounting worldwide about a looming pandemic, a research unit in any country could have accidentally released the resurrected virus that came to be called the Russian flu. In the global rush to head off a possible new pandemic of H1N1 swine flu from Fort Dix through research and vaccination, accidents could have happened anywhere.

Of course, biocontainment facilities and policies have improved dramatically over the past half-century. But at the same time, there has been an equally dramatic proliferation of high-containment labs around the world.

Across the globe, researchers work on dangerous pathogens in labs that are part of biocontainment facilities.

Overreaction. Unintended consequences. Making matters worse. Self-fulfilling prophecy. There is a rich variety of terms to describe how the best intentions can go awry. Still reeling from COVID-19, the world now faces new threats from cross-species jumps of avian flu viruses, mpox viruses and others. It’s critical that we be quick to respond to these emerging threats to prevent yet another global disease conflagration. Quick, but not too quick, history suggests.

Donald S. Burke, Dean Emeritus and Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of Health Science and Policy, and of Epidemiology, at the School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.