News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Maine schools report thousands of restraints and seclusions per year, but the real number is higher

by Eesha Pendharkar, Louisiana Illuminator

May 25, 2025

Maine students have been restrained and secluded more than 22,000 times a year in some years. But the real number of times educators put students in holds, move them against their will and shut them alone in small rooms is likely much higher.

Restraint and seclusion are widely condemned practices that create lasting trauma for students, their families and the educators involved. That’s why every use is supposed to be documented and reported to the state. But over the past decade, only 24 out of more than 250 private schools and public districts in Maine have consistently reported their numbers.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Maine law mandates annual reporting to the Maine Department of Education, however the department did not say whether there was any penalty for failing to report.

Maine law mandates annual reporting to the Maine Department of Education. However, according to Bear Shea, the department’s restraint and seclusion specialist, Maine DOE “has not been given statutory authority or mechanisms to enforce compliance.”

Rather, the department seems to operate under the assumption that a district’s lack of reporting means schools didn’t restrain or seclude any students that year.

“It is possible that if a school district does not have any incidents of restraint and seclusion in a school year, they will not report any data,” said Chloe Teboe, the department spokesperson, when asked about the dozens of districts that aren’t reporting every year, according to publicly available state data. “The Maine DOE can only act on the data that is shared by school districts, as required by statute.”

Atlee Reilly, managing attorney for the advocacy organization Disability Rights Maine, said it’s “beyond unlikely” that districts failing to report have not used restraint or seclusion.

Overall, reporting to the DOE has fallen off in recent years, Reilly told lawmakers on May 9 during discussion of a proposed bill that aims to relax the rules on restraint and seclusion. Many of the state’s largest districts and schools that historically reported frequent use of restraint and seclusion have stopped sharing their numbers in recent years, according to statewide data.

“I know that some schools that have historically reported high numbers of restraints haven’t reported,” Reilly said. “So does that mean that they, all of a sudden, are not restraining or secluding youth? I think probably not.”

At least one school not reporting high use to state

A closer look at the Bangor Regional Program, a school for students with disabilities, reveals how restraint and seclusion practices can go unreported for years.

Bangor Public Schools is responsible for reporting its own numbers, as well as the data for the Bangor Regional Program, which serves students from several area districts. The state database includes numbers from the regional program for one of the past 10 years, after a 2019 investigation found the school had been restraining and secluding students thousands of times each year from 2015 to 2018, more than almost any other school in the state.

During the 2019-20 school year, the regional program used 261 restraints and 325 seclusions on 33 individual students. Internal data provided by Bangor schools to Maine Morning Star in response to a records request shows that in the following years, the program continued using these practices. In 2021-22, the school reported 419 total uses of restraint and seclusion. In 2022-23, use dropped to 187, and in 2023-24, increased to 281.

None of these incidents were reported to the state, according to publicly available state data.

Though Bangor Public Schools reports its data every year, when asked why the regional program’s numbers were not shared with the state, spokesperson Ray Phinney said he didn’t know and couldn’t find out due to recent changes in district leadership.

“The superintendent who oversaw the submission of this is no longer with us,” he said.

The DOE did not respond directly to questions about this school’s lack of reporting, but the spokesperson said the department “reports any data received from school districts and does not make a practice of not publishing it.”

Ben Jones, director of legal and policy initiatives for Lives in the Balance, a Maine-based nonprofit that works with schools to reduce restraint and seclusion, said it’s important for the department to explain what happens when schools like the regional program collect data but don’t report it to the state.

“We still don’t have a true sense of the scope of using these dangerous practices, so this, to me, points the spotlight back at reporting and collecting,” he said. “So what more is DOE doing to ensure the completeness of the data, the completeness of this picture?”

Few districts regularly report data

This underreporting casts doubt on the apparent progress Maine has made in relying less on these practices in the wake of a 2021 law, which specified restraint and seclusion should only be used in emergency situations.

The law was intended to reduce the use of emergency behavioral interventions that are known to be traumatic — particularly for students with disabilities, who are disproportionately affected.

“It’s very difficult to tell if the numbers went down or up after the law change because of underreporting,” Jones said.

In the 2022-23 school year, Maine schools reported 44% fewer incidents of restraint and seclusion in schools than it did four years earlier. But only 140 of Maine’s 300-plus school administrative units submitted their data for that school year. In 2018-19, that number was 213.

I don’t want anyone to think that people in schools are just wanting to put hands on kids. Because it’s traumatic, it’s not good. However, there are times, when for the safety of an individual student or others around that individual, it becomes necessary to restrain or seclude.

– Superintendent Clay Gleason, Maine School Administrative District 6

Only 24 districts have submitted restraint and seclusion data every year for the last decade, a Maine Morning Star analysis found.

Together, they represent fewer than one-quarter of Maine’s roughly 170,000 K-12 students. Only two of the state’s 10 largest districts, Bangor and Maine School Administrative District (MSAD) 6 in the Buxton area, are among them.

In the 2018-19 school year, MSAD 6 staff reported restraining students 150 times and placing them in rooms by themselves 256 times.

By 2022-23, MSAD 6’s use of those tactics, especially seclusions, had dropped considerably. District staff that year reported restraining students 100 times and placing them in seclusion rooms 132 times.

That district’s reliance on restraint and seclusion roughly matches the trend statewide over that period. Across Maine, use of restraint and seclusion peaked in the 2018-19 year at more than 22,000 reported uses, according to the available state data. After passage of the 2021 law restricting their use to instances when a student’s behavior poses an “imminent danger” of serious injury, overall incidents fell to just under 12,600 in the 2022-23 school year — a 44% drop.

“I don’t want anyone to think that people in schools are just wanting to put hands on kids. Because it’s traumatic, it’s not good,” said MSAD 6 Superintendent Clay Gleason. “However, there are times, when for the safety of an individual student or others around that individual, it becomes necessary to restrain or seclude.”

Numbers still high despite underreporting

Despite inconsistent reporting, it’s clear many Maine districts still rely on these practices thousands of times a year. In 2021, data reported directly by schools to the federal government showed that Maine ranked first and second in restraining and secluding students, respectively, per capita. According to an analysis of the most recent national numbers, the state fell to third and fourth per capita.

“These are still extremely high numbers,” said Jones with Lives in the Balance. “Each one of these is a kid being grabbed or put into a closet, and then there’s probably more of it going on based on what we know.”

The number of reported restraints and seclusions vary widely from district to district, noted Alan Cobo-Lewis, director of the Center for Community Inclusion and Disability Studies and associate professor of Psychology at the University of Maine.

Some districts have reported zero incidents for many years, and others like those in the Buxton-area, report large numbers. But “whether they’re model programs, or whether they’re just not reporting their restraints, I don’t think that you can know that without actually visiting schools,” Cobo-Lewis said.

“I have advocated for a while for the department to visit the schools that had high rates and also visit the schools that had zero,” he said.

While the federal government collects this data from districts, there is no federal oversight, and every state has different laws about restraint and seclusion. Some members of Congress have proposed a federal ban on school use of restraint and seclusion, with the most recent legislation introduced in 2023.

The proposal currently before Maine lawmakers would allow districts to move students against their will without reporting it as a restraint and would allow educators more flexibility in determining when they use these practices by decreasing the level of danger posed by a student’s behavior from “serious physical injury” to just “injury.”

Both Jones and Reilly of Disability Rights Maine worry that if the bill passes, schools will no longer have to report incidents where staff move students against their will into classrooms and quiet rooms. That would mean the statewide data on the number of restraints could drop.

“What we’re going to do is take a whole class of stuff — like the physical management of students that I think most people would look at and say, that child’s being restrained — and say it’s no longer restraint,” Reilly said.

He added, “It doesn’t mean that people are going to be putting their hands on kids less.”

From 2014 to 2023, school units reported 55 serious bodily injuries to students and 594 to staff members related to the use of a restraint or seclusion, according to publicly available data. In recent years, the number of students injured while being restrained and secluded has increased, with 22 of those 55 instances reported in the 2022-23 school year, all reported by Biddeford Schools. The southern coastal district did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Most years, the vast majority of districts reported zero injuries.

MSAD 6 in Buxton is one of the only districts that has reported staff and student injuries to the department every year, but Gleason said he did not recall any serious incidents, and did not know what criteria was used by staff who filled out forms.

“There are minor injuries that happen to both staff and students, sometimes with somebody getting a little rug burn or bumping into a desk or something,” he said, explaining the typical ways staff or students might get injured during a restraint or seclusion.

“But I don’t know if it’s a standard kind of thing across districts and how they report it, or if it’s like an internal measure,” he added.

According to state law, school units would not report injuries that do not meet the definition of serious physical injury, according to Shea, the department’s restraint and seclusion specialist. But in practice, “I have talked with many schools and there is a wide range of ways that [school administrative units] choose to report injuries with some tending to report even more minor injuries,” he said.

While the department collects injury data, there is no statewide policy about what districts should do in response to student or staff injuries.

Majority of reports from schools for students with disabilities

When public school districts determine they can’t adequately serve a student with disabilities, some of them are referred to special purpose private schools. Although these schools still receive public funding, Jones said the programs are often insulated from scrutiny.

Having sat through dozens of those placement meetings, Jones said the student’s parents and advocates are hoping that a move would increase support for the child, but that’s not always the case.

Pointing to the high number of reported incidents, Jones said these schools can often be “hotbeds for the inappropriate use of restraint and seclusion.”

Over the past decade, Maine’s special purpose private schools have accounted for roughly 57% of all uses of restraint and seclusion in the state each year, going up to almost 70% in 2019-20, when the state saw the most incidents in a decade.

Though the data from these schools haven’t been consistently included in the state’s annual data, students with disabilities in Maine and nationwide are much more likely to be subject to these practices.

Maine’s special purpose private schools served roughly 850 students in 2022-23 but accounted for 58% of all 7,975 restraints in the state, according to a Maine Morning Star analysis. That same year, they also accounted for about 47% of all seclusions in Maine: 2,154 of 4,618 incidents.

The Margaret Murphy Centers for Children, a special purpose private school with campuses in Auburn, Lewiston, Saco and Turner, has topped the state’s list for seclusion every year since 2014-15; it has also restrained students more than any other school every year since 2017-18, state data shows.

The centers used these practices more than 11,000 times on just 108 students in 2019-20, according to the state data from 2023.

There is no state law restricting an educator from using these practices repeatedly on a particular child. And unless a parent complains and requests a district try a new approach, there is no statewide process for addressing the frequency of incidents.

Margaret Murphy Senior Director Michelle Hathaway attributed those numbers to the severity of the student population’s needs. The school exclusively serves children and young adults (up to age 22) with significant behavioral and developmental challenges, many of whom are referred to the school specifically because of the “intensity or dangerousness of their behaviors,” she said.

They sometimes display aggression — including attempts to hit, choke, or rip out hair — that can pose serious safety risks to themselves or others.

Hathaway wrote in an email that restraints are only used as a “last resort” but argued the law leaves room for interpretation and that ambiguity means some schools may “over-document and over-report.”

For example, she said a staff member holding a 3-year-old’s hand to prevent them from running into a parking lot could technically, under current law, be considered a restraint.

But repeatedly using restraint and seclusion on a small number of students should be a red flag that something is not working, Jones said.

“Of course emergency situations will arise, but after the first few uses of restraint or seclusion, we are no longer talking about emergencies,” he said. “We are talking about predictable behavior that can be planned for, trained for.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

This report was originally published by the Maine Morning Star. It’s part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Maine Morning Star maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Lauren McCauley for questions: info@mainemorningstar.com.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

This report was originally published by the Maine Morning Star. It’s part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Maine Morning Star maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Lauren McCauley for questions: info@mainemorningstar.com.

The post Maine schools report thousands of restraints and seclusions per year, but the real number is higher appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a generally critical view of restraint and seclusion practices in Maine schools, emphasizing the trauma caused by these measures and the systemic underreporting of incidents. It highlights advocacy voices pushing for stricter oversight and transparency, and it questions legislative efforts that would loosen restrictions. The language tends toward advocating for vulnerable populations, especially students with disabilities, which aligns with progressive or center-left perspectives prioritizing social justice and reform. However, it also includes viewpoints from school officials acknowledging safety concerns, which balances the narrative and prevents it from being overtly partisan. Overall, the piece leans center-left by framing restraint and seclusion as harmful practices needing reform while acknowledging complexity.

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Lafayette prosecutor Gary Haynes’ federal bribery trial starts

SUMMARY: Gary Haynes, longtime Lafayette Assistant District Attorney, faces federal trial Monday on bribery, kickback, money laundering, and obstruction charges linked to the 15th Judicial District Attorney’s Office pretrial intervention program. Indicted in September, Haynes allegedly steered participants to a vendor in exchange for bribes, including an $81,000 truck. Co-conspirators, all pleading guilty, are expected to testify against him. Evidence includes wiretaps and consensual recordings. Haynes remains on unpaid administrative leave amid scrutiny for rehiring him after a decade-old bribery scandal shuttered the office. The trial poses significant reputational and legal consequences, with Haynes facing up to 60 years if convicted.

The post Lafayette prosecutor Gary Haynes’ federal bribery trial starts appeared first on thecurrentla.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

NBC 10 News Today: LSU female drum major

SUMMARY: The LSU Golden Band from Tigerland is gearing up for an exciting season, highlighted by senior Catherine Mansfield as only the fourth female drum major in the band’s history. With 325 members, the talented group has spent countless hours perfecting their performance, emphasizing precision, passion, and flawless execution. Mansfield feels the pressure but feeds off fan excitement, while Drum Captain Brayden Ibert praises the youthful, skilled group. Associate Director Simon Holoweiko underscores the dedication behind every drill, footwork, and horn note, ensuring the band delivers a powerful, high-energy show that electrifies game day experiences for LSU fans.

The LSU Tiger Band is gearing up for the 2025 season premiere, marking a historic moment as senior drum major Catherine …

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Clay Higgins continues his atypical quest for political relevance

by Greg LaRose, Louisiana Illuminator

September 7, 2025

For at least a moment earlier this year, U.S. Rep. Clay Higgins was willing to depart from his typical far-right, far-fetched stances to take a position most would label liberal – on a criminal justice matter, of all things.

Yet just months later, the Lafayette Republican is back to his extremist ways. What’s different now is that he appears rudderless, permanently veering to the right to the point where it could be argued he’s merely spinning in political circles.

Heads turned during the spring session of the Louisiana Legislature when Higgins, a former policeman, gave his support to a proposal that would have let people put in Louisiana prisons by non-unanimous juries seek reviews of their cases. The lawman-turned-lawmaker urged the “swift passage” of the bill by state Sen. Royce Duplessis, D-New Orleans, arguing it preserved the U.S. Constitution’s rights to due process and a fair trial.

“You could not have told me in my 42 years on this earth that I would have a letter from Congressman Clay Higgins supporting a bill that I brought,” Duplessis told colleagues on the Senate floor before they resoundingly rejected the measure. Opponents in the Republican supermajority said the policy change would overload prosecutors and court staff.

In recent days, Higgins has come out firing on all cylinders but with no clear direction ascertainable.

On Aug. 29, he sent a letter to House Speaker Mike Johnson saying that he was stepping down from the House Homeland Security Committee after Rep. Andrew Garabino, R-N.Y., was named its new chairman. Higgins, a candidate for the post, appeared dejected after the vote.

“My Republican colleagues have chosen an alternate path for the Committee that I helped to build,” he wrote to Johnson, “a path more in alignment with the less conservative factions of our Conference, factions whose core principles are quite variant from my own conservative perspective on key issues like amnesty, ICE operations, and opposition to the surveillance state.”

That’s the Higgins we’ve come to know – bitter, self-righteous and steered by conspiracy theories. As he still sits on the House Armed Services and the Oversight and Government Reform committees (chairing the latter’s law enforcement subcommittee), there will be ample chances for him to make bluster’s last stand.

And by no means will Higgins limit himself to those matters. A week ago, he urged the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services to withhold federal funding from “organizations that push COVID vaccines on young children.”

It followed his pledge on social media to “defund” the New Orleans Health Department for promoting the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidance on COVID-19 vaccines for children from 6 months to 2 years old.

“State sponsored weakening of the citizenry, absolute injury to our children and calculated decline of fertility,” Higgins wrote in an Aug. 20 X post.

Call me a skeptic, but if there’s a group out there that’s least likely to be anti-fertility, it’s probably pediatricians. It’s not good for their business model.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Higgins’ latest play for political relevance came Thursday when he joined forces with Rep. James Comer, R-Ky., Oversight and Government Reform chairman, to investigate allegations that pharmacy chain CVS Health used “confidential patient information” to lobby the Louisiana Legislature.

Caremark, a CVS subsidiary, is the prescription benefit manager for the health insurance plan that covers state employees in Louisiana. Attorney General Liz Murrill is suing the company, saying it used information gained through that contract to send text messages to state employees asking them to oppose proposed legislation. The bill in question would have prohibited prescription benefit managers from co-owning pharmacies. Ultimately, lawmakers opted for a less aggressive, transparency measure with the support of independent pharmacies.

Critics consider the co-ownership arrangement self-serving, as the management entities have a direct say in how their affiliated pharmacies price – and profit from – prescription drugs.

Comer and Higgins have requested CVS Health president and CEO David Joyner provide a slate of records to aid in their investigation.

David Whitrap, who handles external relations for CVS, said in an email the company plans to respond to Comer and Higgins. With regards to the text messages, its communication with customers, patients and the community “was consistent with the law,” he said.

As much as he wants to position himself to the far right, Higgins’ involvement in accountability efforts such as this makes him a centrist – at least on this issue. The battle against pharmacy benefit managers is a bipartisan one, with both sides looking to claim the win for bringing down prescription drug and health insurance costs.

Regardless, it’s a welcome moment of lucidity from Higgins, much like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s demand for the U.S. Department of Justice to produce all its files on Jeffrey Epstein.

No one expects it, but it’s certainly welcomed.

For Higgins, more frequent stances like this could help him emerge from the shadow of Louisiana’s more prominent Republicans in the House – Speaker Johnson, Majority Leader Steve Scalise and Rep. Julia Letlow, a member of the powerful House Appropriations Committee.

But if history portends what lies ahead from Higgins, expect him to once again find his comfort zone on the fringes.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post Clay Higgins continues his atypical quest for political relevance appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content critiques U.S. Rep. Clay Higgins from a perspective that highlights his far-right positions and labels some of his views as extremist, while also acknowledging occasional bipartisan or centrist actions. The tone is skeptical of conservative stances, particularly on issues like criminal justice, immigration, and COVID-19 vaccines, and it uses language that suggests disapproval of right-wing conspiracy theories. However, it also recognizes moments when Higgins aligns with more moderate or bipartisan efforts, indicating a nuanced but generally center-left leaning viewpoint.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Trump proposed getting rid of FEMA, but his review council seems focused on reforming the agency

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Missouri joins dozens of states in eliminating ‘luxury’ tax on diapers, period products

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

Tennessee ranks near the top for ICE arrests

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

Texas high school football scores for Thursday, Sept. 4

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Brandon residents want answers, guarantees about data center

-

The Conversation6 days ago

What is AI slop? A technologist explains this new and largely unwelcome form of online content

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Every fall there’s a government shutdown warning. This time it could happen.

-

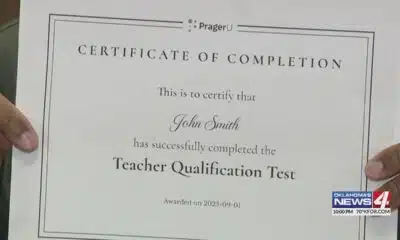

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

Test taker finds it's impossible to fail 'woke' teacher assessment