News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Laughs, tears, memories of WRAL legend Charlie Gaddy

SUMMARY: Charlie Gaddy, a WRAL legend and North Carolina’s trusted news anchor for over two decades, was laid to rest in a heartfelt funeral at Edon Street United Methodist Church. Family, friends, and coworkers shared stories celebrating his 93 years filled with laughter, compassion, and integrity. Known for his warmth, reliability, and deep connection to viewers, Gaddy was a father figure and mentor to many journalists. His empathy shone through moments like his coverage of Raleigh tornado victims. Though gone, his legacy lives on in the countless lives he touched, both on and off the screen.

Charlie Gaddy was remembered in an emotional, packed ceremony on June 26, 2025.

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

The gerrymandering mess threatens to spiral out of control

SUMMARY: Demonstrators gathered outside the U.S. Supreme Court to demand fair districting maps amid growing concerns about gerrymandering, where politicians manipulate electoral maps for partisan gain. This practice has escalated alarmingly, threatening democratic fairness. In Texas, Republicans, encouraged by President Trump, are attempting to rig the 2026 midterm election maps in unprecedented ways, inspiring similar actions by both parties nationwide. Such gerrymandering undermines competitive elections and marginalizes moderate candidates, as seen repeatedly in states like North Carolina. This manipulation poses a significant threat to American democracy, and urgent action from congressional leaders is needed to stop it.

— Rob Schofield, NC Newsline

The post The gerrymandering mess threatens to spiral out of control appeared first on ncnewsline.com

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

In Depth with Dan: Answering viewer questions about flesh-eating bacteria, digital licenses

SUMMARY: In this Monday mailbag, Dan addresses viewer questions on three topics. First, North Carolina’s Vibrio bacteria risk in summer coastal waters: cooked shellfish is safe, but raw consumption is risky due to bacteria concentrating in oysters. Second, digital driver’s licenses in North Carolina face delays; although legalized in 2023, full rollout may not occur until 2026, with other states also lagging behind. Lastly, Dan explains flood-damaged vehicles after recent storms: flooded cars must be branded as such, but scams occur. He shares tips to spot flood damage when buying used cars, emphasizing caution and thorough inspection.

WRAL anchor/reporter Dan Haggerty answered viewer questions about a flesh-eating bacteria in North Carolina and the legalization of digital driver’s licenses.

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

The latest update on Tropical Storm Erin

SUMMARY: Tropical Storm Erin is forecast to become a Category 1 hurricane by Thursday and remain well out to sea through Saturday, near the Lesser Antilles northeast of Puerto Rico. Models show it moving west, then curving north toward Bermuda or Florida, but uncertainty remains high beyond next week. The American and European models suggest it could pass between Bermuda and Hatteras, causing higher surf midweek. Due to large forecast errors, the storm’s exact path is unclear, ranging from north of New York to the Florida panhandle. Residents should prepare hurricane kits and stay updated, with clearer guidance expected by Thursday or Friday.

Will Erin cause problems for the East Coast? Here’s the latest on Monday evening.

https://abc11.com/post/tracking-tropics-tropical-storm-erin-forms-eastern-tropical-atlantic-cabo-verde-islands/17499988/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

X: https://x.com/ABC11_WTVD

-

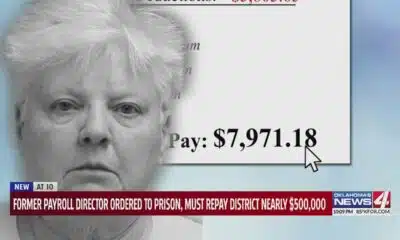

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

Former payroll director ordered to prison, must repay district nearly $500,000

-

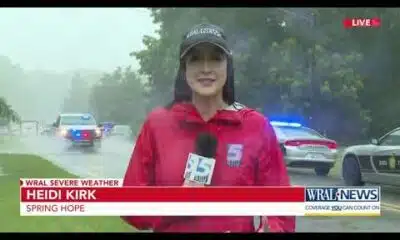

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

Two people unaccounted for in Spring Lake after flash flooding

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

Trump’s new tariffs take effect. Here’s how Tennesseans could be impacted

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

Jim Lovell, Apollo 13 moon mission leader, dies at 97

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

Man accused of running over Kansas City teacher with car before shooting, killing her

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

Tulsa, OKC Resort to Hostile Architecture to Deter Homeless Encampments

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

Drugs, stolen vehicles and illegal firearms allegedly found in Slidell home

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

Why congressional redistricting is blowing up across the US this summer