News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

K+20: Katrina showed how crucial federal funding is after a disaster. How much will remain?

by Julie O’Donoghue, Louisiana Illuminator

August 29, 2025

For years after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleanians made the Federal Emergency Management Agency the butt of their bitter jokes.

Anti-FEMA sentiment was so high in Louisiana that local businesses started selling T-shirts a couple of months after the storm lampooning the federal agency with slogans like “Where’s FEMA?” and “FEMA stands for Federal Employees Missing in Action”.

The sentiment is understandable. Almost a half dozen federal investigations launched in the six months after Hurricane Katrina made landfall Aug. 29, 2005 – and turned into the country’s most catastrophic natural disaster – determined FEMA failed in nearly every way to respond to the storm.

“Hurricane Katrina exposed flaws in the structure of FEMA and DHS that are too substantial to mend,” concluded a 2006 U.S. Senate report titled “Hurricane Katrina: A Nation Still Unprepared.”

Yet 20 years after the agency’s feckless Katrina response, some Louisiana leaders find themselves in the awkward position of having to defend FEMA.

President Donald Trump has made it clear he wants the federal government to play less of a role in natural disaster response, raising concerns that state and local governments might need to cover more of their recovery costs.

Such a change would likely affect Louisiana more than almost every other state in the country.

Since Katrina, Louisiana has received more public and individual assistance from FEMA ($12.6 billion) than all states but Florida ($16.6 billion) and New York ($19.4 billion), according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which tracks federal disaster spending.

The money helped Louisiana respond to 25 extreme weather events, including 11 hurricanes, six floods and one ice storm, over the past two decades.

That FEMA figure doesn’t account for all of the money Louisiana has received in the wake of Katrina. There was another $11 billion from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development went to the Road Home program to rebuild housing. All told, the federal government put an unprecedented $76 billion toward Louisiana’s recovery from the 2005 storm.

Louisiana simply wouldn’t be able to handle the financial burden of major disaster response without significant support from the federal government, according to several former state officials interviewed. Storms with far less impact than Katrina have the ability to overwhelm the state’s assets, they said.

If Louisiana has to worry about covering more disaster recovery costs, the state will have less money to spend on schools, universities, roads, bridges and economic development.

“If we didn’t have the federal money, we would be in a terrible mess, and we would have been in a terrible mess from Katrina going forward,” said Jay Dardenne, Louisiana’s former lieutenant governor and state budget chief for former Gov. John Bel Edwards.

Uncertainty at FEMA

To what extent Trump will pull back on federal disaster assistance isn’t clear.

As recently as June, the president said he would push to eliminate FEMA altogether. He then backed off that rhetoric after July 4th weekend flooding in Texas killed at least 136 people, including children attending a sleepaway camp. His administration’s response was directly criticized.

Still, the Trump administration has already made several preliminary changes to FEMA that alarm emergency response experts. The agency has reduced staff and some of those who remain have been asked to help with hiring immigration enforcement agents instead of working on disaster relief.

The FEMA cuts come on top of those to the National Hurricane Center and other federal programs that provide crucial information to hurricane-prone states and help them ready for incoming storms.

Some reforms Congress enacted in the year after Katrina to strengthen FEMA have also been ignored. A law requiring FEMA’s director to have experience in emergency response and disaster recovery isn’t being followed. Trump’s acting FEMA administrator David Richardson previously oversaw counter terrorism programs but does not have natural disaster management experience.

There are also concerns about whether a new policy delayed assistance during the Texas flood, similar to what unfolded in the aftermath of Katrina.

Due to a bureaucratic breakdown 20 years ago, FEMA failed to promptly provide boats for search-and-rescue teams in New Orleans, even after federal officials knew flooding was widespread, according to a U.S. Senate report from 2006.

This past July, several questions were raised about whether search-and-rescue teams were delayed during the Texas flood because Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem now requires every FEMA contract over $100,000 to be approved personally by her, the Associated Press reported. The Trump administration has denied those allegations.

The ability of Louisiana and other states to respond to catastrophic weather with their own staff would also likely be impacted if Trump changes the traditional funding reimbursements for recovery efforts.

“The federal government will have a lasting role in responding to and funding the impact of disasters; local and state governments simply do not have the resources to do so,” said Paul Rainwater, who was executive director of the Louisiana Recovery Authority that managed federal funding for state rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Katrina. He went on to serve as former Gov. Bobby Jindal’s chief of staff and budget czar.

“The question the Trump administration faces, given some of its comments about FEMA, is: When will a White House step in and help?” he said.

Presidential discretion

The president has a significant say in when FEMA provides funding to states after natural disasters, as well as how much money states or local governments receive.

When a state is overwhelmed by a catastrophic event, a governor makes a formal request of the president for federal assistance. FEMA starts to provide help to the state authorities after it is granted.

Since returning to office in January, Trump has denied disaster relief that was expected to be approved. His decisions have affected liberal-leaning states such as Maryland and Washington and more conservative ones like West Virginia.

He even stalled for a month on accepting a disaster declaration from Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who personally knows Trump and served as his press secretary during his first term as president.

As president, Trump has the ability to not only approve federal assistance, but to also increase the share of the state or local costs that FEMA will reimburse. For example, federal law gives presidents the discretion to reduce or waive the requirement for a state or local government to cover 25% of the cost of debris removal after a storm.

Louisiana has benefited from a reduction of these local financial responsibilities for nine weather events in the past 25 years, including for hurricanes Ida (2021), Laura (2020), Ike (2008), Gustav (2008), Rita (2005), Katrina (2005) and Ivan (2004). The 2016 Baton Rouge-area floods and a severe ice storm in 2001 were also approved for enhanced federal assistance, according to a 2023 Congressional report.

But all the upheaval should be a signal to local and state officials to prepare as if that extra FEMA help might not be coming their way, former FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell, who worked for President Joe Biden, said in a call with reporters this week.

“There are, right now, a lot of questions about whether any of those costs are going to be eligible for reimbursement,” Criswell said. “You need to put plans in place to make sure that you can do it, regardless of whether you get federal support.”

U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., said he personally advocated for the federal government to cover more disaster recovery bills after Hurricane Laura, which hit Southwest Louisiana, and the 2016 flooding.

Sometimes a disaster is so profound that local governments have a hard time coming up with the tax revenue to cover their share of the recovery. If people lose their homes and are displaced, as happened after Katrina, cities and parishes won’t have much money to put toward cleanup, Cassidy said.

“When you destroy a community, you destroy their ability to raise tax money,” he said in an interview.

Jindal, who served as Louisiana’s governor from 2008-16 and was a congressman during Hurricane Katrina, said he thinks the federal government will always be an important partner in major disasters. But states and local governments should take on more responsibility for smaller events.

“There are many day-to-day disasters that many state and local governments can handle themselves,” Jindal said. “For the bigger disasters that can overwhelm, you still want to have some federal role.”

It’s also crucial that local and state officials know what to expect from the federal government so they can be prepared, said Jindal, who was governor when hurricanes Gustav and Ike hit Louisiana.

“I think it’s important to have clear rules ahead of time,” he said.

Landry: Louisiana shouldn’t worry about FEMA

Trump may have denied disaster relief to other states, but Gov. Jeff Landry said Louisiana has nothing to worry about when it comes to FEMA because of his good relationship with the administration.

“I think it’s all just a bunch of media hype trying to scare people. We’re ready for hurricane season,” the governor told reporters this week.

Landry has a close relationship with Noem and said Trump’s homeland security leader has already responded to requests for assistance for matters in Lake Charles and Terrebonne Parish this year.

“What Kristi Noem has done lately, I mean, we just call her, and we say, ‘These are projects that need to be moved,’” Landry said.

Louisiana is one of only a few states that has a local representative on Trump’s FEMA review council, which is supposed to make recommendations on reforming the agency this fall.

One of the council’s 12 members, who include Noem and Department of Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, is Louisiana native Mark Cooper, Jindal’s former head of emergency management and former Gov. Edwards’ chief of staff.

“Obviously, Louisiana is playing a big role in this reimagining for FEMA,” Cooper said this week in an interview from Oklahoma where the review council was meeting. “We’re being heard. Louisiana is being heard as part of this process.”

Cooper said the council already met directly with Louisiana emergency response officials in the Landry administration. It held its second public meeting in New Orleans in July at his suggestion.

The council has made no decisions about whether FEMA’s reimbursement policies for state and local governments should change, Cooper said, but he suggested more might be asked of states.

“We need to do more to help states to be more self-reliant and resilient,” he said.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post K+20: Katrina showed how crucial federal funding is after a disaster. How much will remain? appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of federal disaster relief, particularly regarding FEMA, while highlighting the ongoing necessity and benefit of federal assistance for disaster-prone states such as Louisiana. It underscores the shortcomings and controversial decisions under Trump, including staffing cuts and hesitance to approve disaster aid, often citing sources and officials who lean toward advocating for stronger government roles in disaster recovery. While it provides some conservative perspectives, such as Governor Landry’s and former Governor Jindal’s comments about state responsibility and positive relations with the current administration, the overall tone emphasizes support for federal involvement and skepticism toward efforts to reduce it—both typical of center-left media framing that stresses government responsibility in social support systems.

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Remembering 20 years after Hurricane Katrina

SUMMARY: On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana as a Category 3 storm with 125 mph winds, making landfall in Plaquemines Parish. It became the third most intense U.S. landfalling hurricane, causing massive devastation and loss of life, with impacts still felt 20 years later. Across New Orleans, Jefferson, St. Tammany, St. Charles, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Parishes, officials and first responders reflected on the tragedy, honoring resilience, sacrifice, and ongoing recovery efforts. Leaders emphasized remembrance, community strength, and commitment to building safer, stronger futures while mourning those lost and celebrating the courage of survivors.

Read the full article

The post Remembering 20 years after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on wgno.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

Over $600k awarded for security upgrades at Jefferson Parish schools

SUMMARY: Jefferson Parish Schools received 13 grants totaling $605,600 from the Louisiana Center for Safe Schools program to enhance school security. Each school can receive up to $50,000 to improve facilities and create secure entry vestibules, which will control access and screen visitors before entering campuses. Superintendent Dr. James Gray emphasized the grants’ importance in ensuring safe learning environments, while COO Patrick Jenkins highlighted the peace of mind these upgrades provide. Chief District Affairs Officer Dr. LaDinah Carter noted the commitment to student and staff well-being. Specific schools received varying amounts, with most allocated $50,000 for these security enhancements.

The post Over $600k awarded for security upgrades at Jefferson Parish schools appeared first on wgno.com

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed

K+20: Katrina alters local health care landscape, though underlying ills still the same

by Wesley Muller, Louisiana Illuminator

August 28, 2025

When Dr. Granville Morse began his shift at Charity Hospital’s emergency room on Aug. 27, 2005, neither he nor his colleagues knew they would admit what would be the last patients in the institution’s 269-year history. Even as Hurricane Katrina undermined New Orleans’ faulty levees and crippled its power infrastructure two days later, he and others on staff tended to a surge in people needing health care.

They included nursing home residents evacuated to the hospital amidst rising floodwaters, only to be moved out once again after Charity’s basement became submerged and its generators were rendered useless. Morse helped bring patients across the flooded street to the helipad at Tulane Medical Center, which was conducting its own evacuation.

“People were trying to do the best they could,” he said. “We figured out a way to care for them.”

Before Katrina, Charity and other local hospital emergency rooms were often the primary care provider for a substantial portion of New Orleans-area residents, more than 20% of whom had no health insurance in 2005 according to the Congressional Research Service.

Out of 16 area hospitals, 13 had to close after the storm. Most have since reopened, some as specialty care centers, but Charity Hospital and Lindy Boggs Medical Center in Mid-City remain vacant. Two new acute-care facilities, University Medical Center and New Orleans East Hospital, have been added.

The decision to abandon Charity created great angst among residents whose families had relied on the hospital for generations. Yet local medical industry leaders say the city and region are now delivering a better standard of care while also able to better withstand a major natural disaster.

When Hurricane Ida knocked out power for much of the New Orleans region in 2021, University Medical Center operated off the grid for 11 days without incident, said Dr. John Heaton, president and chief medical officer of LCMC Health, which operates the hospital.

“It’s gonna have to be a really big one for UMC to evacuate,” Heaton said. “UMC is built like a fortress. You can barely tell the wind’s blowing outside.”

LCMC Health and Ochsner Health System, two of the state’s leading health care providers, own or run many medical facilities in the region. Both have also opened or acquired dozens of urgent care clinics, in part to meet post-Katrina care needs and in line with a national move away from hospital-based care.

“The shuttering of some of the hospitals after Katrina allowed us to back up and think about how to develop health care in actual neighborhoods … where patients are within walking or biking distance,” said Dr. Michael Griffin, CEO of DePaul Community Health Centers. The organization has expanded from one New Orleans-area clinic to 11 since 2005.

Compared with other southeastern states, Louisiana has markedly better access to care, according to data from the United Health Foundation, which conducts one of the nation’s longest running state-by-state health assessments. However, the Pelican State has been unable to improve its overall health ranking from the worst in the nation. The foundation ranked Louisiana 50th both in 2004 and in its most recent report from 2024.

Affordable Care Act fills care gaps

In the immediate wake of Katrina’s devastation, a handful of local medical students and residents set up six makeshift medical aid stations around the city. Their goal was to care for the uninsured and marginalized populations that had previously relied on Charity Hospital.

This was the genesis for the community-centered model of health care for New Orleans, Morse said.

Morse credits Tulane physician Dr. Karen DeSalvo for spearheading the community health model now present in Louisiana. She would go on to lead the city health department from 2011-14 and join the Obama administration as the assistant U.S. health secretary. DeSalvo is now chief medical officer for Google.

“There was no doubt in my mind that we could not return to a system where we trained our students in hospital based clinics and miss the opportunity to embed them in the community.” DeSalvo told a congressional committee in 2009.

For generations, low-income, uninsured and largely minority citizens relied on Charity Hospital for their medical care. But the hospital was overwhelmed and underfunded, DeSalvo told lawmakers. If patients missed an appointment for any reason, it could be a 12-month wait until the next available appointment, so most patients accessed the system through the emergency room, she said.

The same was true at some of the city’s other hospitals, according to Griffin.

“Those were very vital and critical access points for the community,” he said.

Often when uninsured patients were treated at emergency rooms, they couldn’t afford follow-up care from Charity and other hospitals. At the time, Medicaid didn’t cover the entire cost for health care providers.

“Many hospitals avoided taking Medicaid patients because they couldn’t afford to,” Heaton said. “A lot of advanced therapies just weren’t available (to patients).”

While urgent care and outpatient facilities changed the local health care landscape in the decade after Hurricane Katrina, medical professionals credit a major policy change with improving outcomes for their low-income patients.

In 2016, Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards chose to expand Medicaid services through funding provided under the Affordable Care Act. His Republican predecessor, Bobby Jindal, had shunned expansion while in office.

More than 433,000 Louisiana residents enrolled for the coverage within the first year it was available, state figures show. As of 2022, the number had increased to 638,000, largely the result of relaxed Medicaid rules during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As of 2023, more than 133,000 New Orleans residents, or 36.5% of the city’s population, were covered under Medicaid. Updated official data isn’t available, but the count has likely dropped in the past two years through state efforts to cull the rolls once the pandemic standards expired.

Studies have shown the Affordable Care Act helped fill health care gaps Katrina left in Louisiana through significant funding for federally qualified health centers, which provide care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay. The Louisiana Department of Health estimated 45 such centers existed in the state before Katrina. Over the past 20 years, that number has grown to more than 260, according to federal data.

The new federally qualified health centers include DePaul’s clinics, some of which offer services that were once only found at large hospitals. Its nonprofit clinics typically provide primary care, mental health, dental, podiatry, optometry and pharmacy services — all in one building or complex and often within walking or biking distance to the people who need it most, Griffin said.

“You’re always going to need hospitals,” Griffin said. “But access has definitely improved.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Poverty rates unchanged over 20 years

Dr. Gerry Cvitanovich opened his first urgent care clinic in Kenner in 2002 and was building a second one in Metairie right before Katrina hit. He reopened his Kenner clinic without electricity about 10 days after the storm and began seeing swarms of new patients with different kinds of ailments. Many needed medication refills because they ran out during the storm.

“We were overrun,” Cvitanovich said. “We were overrun with people who needed basic things.”

He recalls seeing patients who had relied on Charity Hospital for their care but had none of their medical records available. The move to digital medical records since the storm has been a great benefit, particularly when patients are displaced by disasters, he said.

Cvitanovich went on to open 14 urgent care clinics in the New Orleans region, eventually selling them to Ochsner Health System in 2017. He’s now part of the system’s medical staff and has served as Jefferson Parish coroner since 2012.

The doctor agreed that health care has become more accessible since Katrina but said access is only one part of the equation to making people healthier.

More change ahead for New Orleans public schools 20 years after Katrina

Studies have shown significant links between poverty and health. People with limited finances often have more difficulty obtaining health insurance or paying for expensive procedures and medications. Factors such as limited access to healthy foods and higher instances of violence can increase stress and the accompanying health risks.

Residents of impoverished communities are at increased risk for chronic disease, higher mortality, lower life expectancy and mental disorders, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The agency also points to natural disasters and pollution as drivers of poverty and poor health in Louisiana.

Before Katrina, approximately 23% of New Orleans residents were living below the federal poverty line — $19,350 for a family of four, according to federal data. Over 20 years, the city’s poverty rate has shown next to no progress, now sitting at 22.6%, according to the Federal Reserve.

Louisiana as a whole has seen a similar trend. The state poverty rate was 19.4% in 2004 and is now at 18.9%, with the poverty line set at $32,150 for a four-person household.

Children make up the largest age group of those experiencing poverty, and this too is more prominent in Louisiana than any other state, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Childhood poverty is associated with developmental delays, toxic stress, chronic illness and nutritional deficits, according to the health department.

In response to these trends, Griffin said the community health care model has been adapted to include school-based clinics. DePaul now provides services, with parental consent, at 23 New Orleans-area schools. The basic idea is to treat patients where they are and closer to home because some people cannot take off work to see a doctor or have no means of reliable transportation, he said.

When possible, LCMC Health goes beyond its medical care role to address public health issues, Heaton said. For example, it has distributed gun safes to parents at Children’s Hospital.

“It’s really not our purview,” Heaton said, adding that public agencies need to address underlying socioeconomic factors behind poor health outcomes in the state.

Morse agreed that the government and other organizations have a larger role to play when it comes to health care.

“There’s only so much we can do,” Morse said. “Health systems are more prepared but only as good as the systems around it.”

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: info@lailluminator.com.

The post K+20: Katrina alters local health care landscape, though underlying ills still the same appeared first on lailluminator.com

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content leans center-left, primarily due to its favorable depiction of public health initiatives, Medicaid expansion, and community-based health care reforms following Hurricane Katrina. It highlights the positive impacts of Democratic policy decisions, such as Medicaid expansion under Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards and the Affordable Care Act, while acknowledging systemic issues like poverty and healthcare access. The article focuses on social determinants of health and the role of government programs without heavy criticism of either political side, which grounds it in a thoughtful, progressive perspective oriented toward public welfare and social equity.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

Racism Wrapped in Rural Warmth

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

DEA agents uncover 'torture chamber,' buried drugs and bones at Kentucky home

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Donors to private school voucher program removed from Missouri transparency site

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

Ukraine’s independence-era voices say Russia’s effort to keep control has lasted decades

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

Texas Democrats’ walkout prompts GOP retribution

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

Child in north Alabama has measles, says Alabama Department of Public Health

-

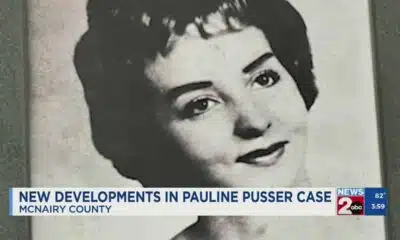

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed2 days ago

New developments in Pauline Pusser case

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

A marsh bird found in Tennessee wetlands is endangered. FWS is drafting a plan.