News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

It’s time for a millionaire’s tax in North Carolina

SUMMARY: For over a decade, North Carolina has granted income tax breaks to the wealthiest while neglecting essential services. The U.S. Congress plans to extend federal tax cuts favoring the rich, even as many residents face health care and food assistance losses. Some state lawmakers propose Medicaid work reporting requirements that could strip nearly 500,000 people of health care. Advocates urge a millionaire’s tax—7% on incomes over \$1 million—to raise nearly \$1 billion annually, protecting services without affecting most residents. Current flat taxes benefit millionaires disproportionately, while Senate proposals risk further cuts favoring the wealthy over public needs.

The post It’s time for a millionaire’s tax in North Carolina appeared first on ncnewsline.com

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

In Depth with Dan: Answering viewer questions about flesh-eating bacteria, digital licenses

SUMMARY: In this Monday mailbag, Dan addresses viewer questions on three topics. First, North Carolina’s Vibrio bacteria risk in summer coastal waters: cooked shellfish is safe, but raw consumption is risky due to bacteria concentrating in oysters. Second, digital driver’s licenses in North Carolina face delays; although legalized in 2023, full rollout may not occur until 2026, with other states also lagging behind. Lastly, Dan explains flood-damaged vehicles after recent storms: flooded cars must be branded as such, but scams occur. He shares tips to spot flood damage when buying used cars, emphasizing caution and thorough inspection.

WRAL anchor/reporter Dan Haggerty answered viewer questions about a flesh-eating bacteria in North Carolina and the legalization of digital driver’s licenses.

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

The latest update on Tropical Storm Erin

SUMMARY: Tropical Storm Erin is forecast to become a Category 1 hurricane by Thursday and remain well out to sea through Saturday, near the Lesser Antilles northeast of Puerto Rico. Models show it moving west, then curving north toward Bermuda or Florida, but uncertainty remains high beyond next week. The American and European models suggest it could pass between Bermuda and Hatteras, causing higher surf midweek. Due to large forecast errors, the storm’s exact path is unclear, ranging from north of New York to the Florida panhandle. Residents should prepare hurricane kits and stay updated, with clearer guidance expected by Thursday or Friday.

Will Erin cause problems for the East Coast? Here’s the latest on Monday evening.

https://abc11.com/post/tracking-tropics-tropical-storm-erin-forms-eastern-tropical-atlantic-cabo-verde-islands/17499988/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

X: https://x.com/ABC11_WTVD

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Body of missing NC teen found in Florida, family says

SUMMARY: The body of missing North Carolina teen Gio Gio was found in Bradenton, Florida, confirmed by his family. Originally, Gio Gio was supposed to be picked up by relatives after meeting cousins in Florida, but he disappeared after texting his mother for help. His family’s private investigators, not the police, discovered his body near I-75 after police had initially searched the area. Gio Gio’s mother expressed her heartbreak on Facebook, calling it every parent’s worst nightmare. The investigation continues, focusing on the timeline after Gio Gio entered the car with his cousins. An autopsy is pending, with no immediate signs of foul play.

The body of Giovanni Pelletier was found in a retention pond, authorities said, and his mom is living “every parent’s worst nightmare.”

https://abc11.com/post/giovanni-pelletier-body-missing-18-year-old-north-carolina-found-pond-where-last-seen-family-says/17483056/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

X: https://x.com/ABC11_WTVD

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

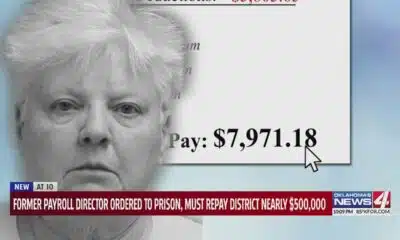

Former payroll director ordered to prison, must repay district nearly $500,000

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

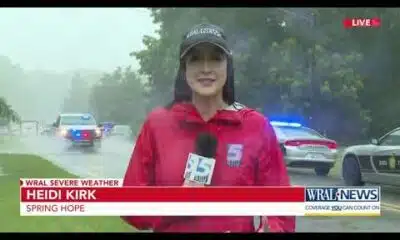

Two people unaccounted for in Spring Lake after flash flooding

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

Trump’s new tariffs take effect. Here’s how Tennesseans could be impacted

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

Jim Lovell, Apollo 13 moon mission leader, dies at 97

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed4 days ago

Man accused of running over Kansas City teacher with car before shooting, killing her

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

Tulsa, OKC Resort to Hostile Architecture to Deter Homeless Encampments

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed5 days ago

Arkansas courts director elected to national board of judicial administrators

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

Drugs, stolen vehicles and illegal firearms allegedly found in Slidell home