News from the South - Texas News Feed

Inside Fort Worth’s Narcotic Farm Experiment

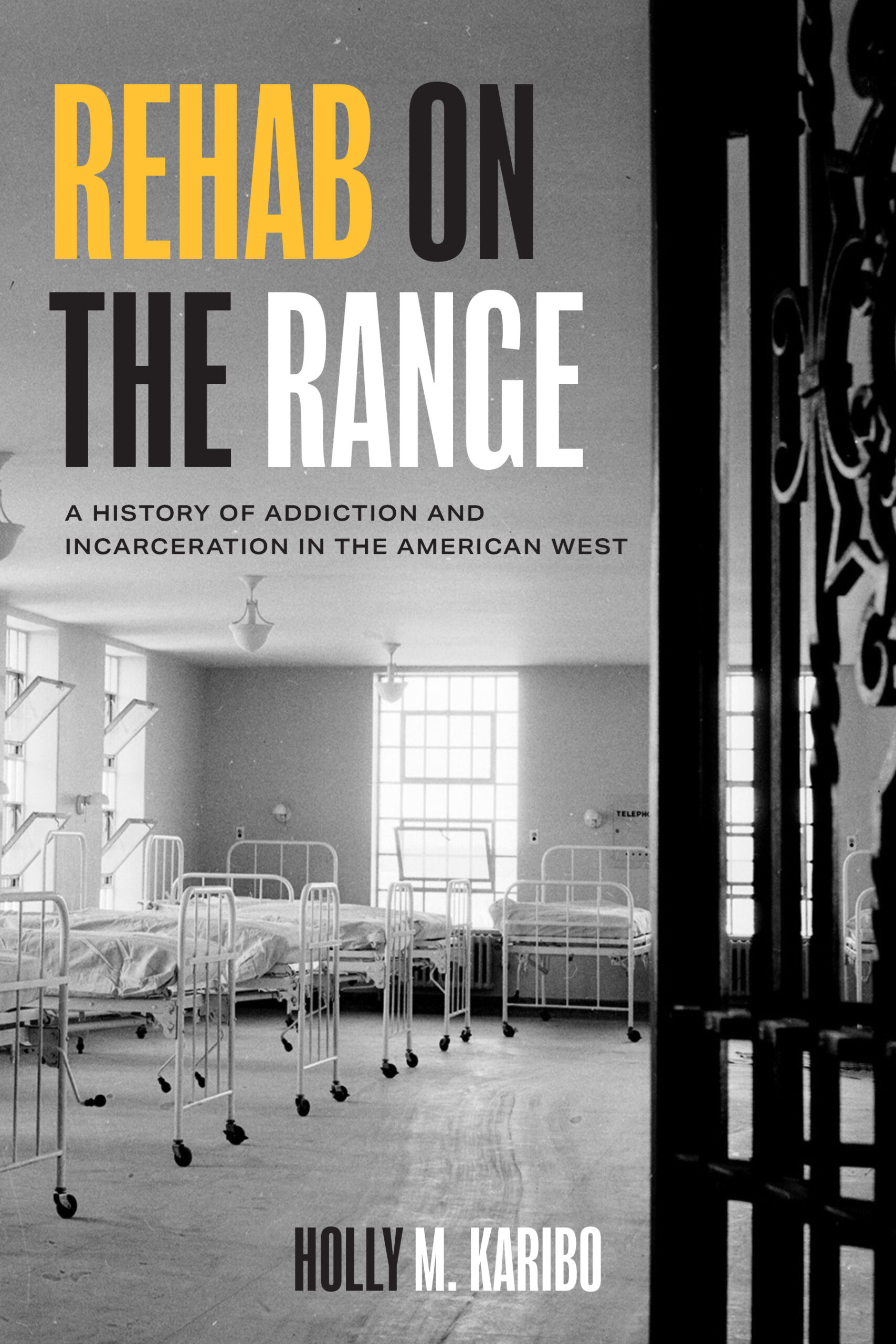

Texas’ history of addiction treatment can be seen as a dance in place: public opinion swings, the Legislature takes one step forward, then two political steps back. Ultimately, little progress is made. Today’s attitudes aren’t dissimilar to the century-old ones described in historian Holly M. Karibo’s new book, Rehab on the Range: A History of Addiction and Incarceration in the American West (University of Texas Press, November 2024).

As Karibo acknowledges in her introduction, the book’s many historical arguments “will likely sound very familiar to twenty-first century readers.” Moral panic about opiates and the shifting demographics of drug users. Doctors withholding care out of very real fear of legal retribution. Fierce disagreements over whether addiction is a medical, legal, or societal issue.

She lays out a detailed institutional history of one experimental rehab center in Texas, a place meant to be a “radical reimagining of the nation’s approach to addiction.” Plans for the center drummed up “unyielding optimism that this new program would provide a modern fix to a modern problem.”

But the Fort Worth experiment ultimately left a complicated legacy.

In the early 20th century, new federal drug prohibition laws were reshaping the societal and penal landscape. It’s against this backdrop that Texans took a central role in the attempt to balance punishment with treatment for the growing percentage of the U.S. population addicted to drugs.

“THIS EXPANSIVE INSTITUTION WAS ULTIMATELY MIRED IN THE NATION’S COMMITMENT TO INCARCERATION.”

In 1931, the burgeoning oil city of Fort Worth scored a massive federal investment in the form of an experimental “narcotic farm”—a setup meant to provide novel addiction treatment to people in a quasi-carceral setting.(Though Karibo argues there’s no such thing as “soft incarceration”—especially when any unauthorized attempt to leave could land you in prison.)

This farm and its sister institution in Kentucky treated volunteer patients struggling with addiction, as well as people sent there because of run-ins with the law. The creation of these facilities constituted “one of the longest-running and most expansive federal experiments in drug addiction treatment in the nation’s history,” Karibo writes. What set the Fort Worth facility apart from older clinics was its focus not just on physical detox, but on psychotherapy as a treatment for addiction. The facility also followed the playbook of Texas prisons by using manual farm labor as a dubious rehabilitation tool.

The Fort Worth center was supposed to resemble a college campus, rather than a prison. It promised good food, a calm environment, and stability. But Karibo writes this expectation “vastly differed from what many patients experienced.”

Rehab on the Range emphasizes the context of the nation’s long churn treating and penalizing drug use while simultaneously zooming in on the details and key players in Fort Worth’s narcotic farm experiment, which finally ended in the 1970s after three decades of tumult.

Exhaustively researched, Karibo’s work at times reads like an academic treatise, at times like investigative journalism. She pored over testimonials, reports, and patient demographic data to pluck out stories and trends that highlight the humanity within the walls of these facilities.

It’s also a sometimes painfully familiar look at the uphill battle for progressive—if flawed—drug policies.

When the Fort Worth facility opened in 1938, efforts were made to train incoming staff on how to treat people with addiction as patients, not prisoners, even if they had been sent there based on a criminal penalty or transferred from a prison. Karibo writes that its high-ranking medical personnel were “deeply concerned that preconceived stereotypes about addicts would undermine the effectiveness of the treatment program.” But the training did not eliminate deeply held biases among both patients and staff, the book states. The roots of the stigma ran deep, creating cracks in the experiment from the outset.

The political landscape in which such experiments take place largely determines how successful they can be. In the case of the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, the post-World War II surge of the international drug trade coincided with a waning of political support for treatment and a shift toward punitive laws, including minimum sentences for drug crimes. In 1957, Karibo writes, the Texas Legislature voted unanimously to support the death penalty for selling drugs to minors.

That’s a familiar rallying cry: In 2024, Donald Trump called for the death penalty for drug traffickers while on the presidential campaign trail.

The cycle of increasing punitive policies boosts the population of incarcerated people with addiction issues. Karibo writes that as more people were locked up for drug crimes in the early 20th century, people blamed them—and their assumed moral failures and character flaws—for increased federal prison unrest, largely ignoring that the general increase in the incarcerated population was stretching the physical limits of prisons and staff. The idea of establishing federal drug treatment facilities was a pressure release valve for prisons disguised as a progressive policy.

“This expansive institution … was ultimately mired in the nation’s commitment to incarceration as a solution to the ‘drug problem,’” she concludes.

Drug use proliferated in the Fort Worth facility, as it does in Texas prisons today. Rehab on the Range outlines the factors that kept people addicted even in treatment. Paltry guard pay created incentives for staff to help funnel drugs inside for a price. Dubious treatment techniques boosted animosity and hopelessness among patients. Complete isolation from the pressures of the outside world—and a lack of meaningful follow-up care—often led to relapse upon release.

Rehab on the Range intelligently describes one of the nation’s first and largest experiments in federally funded drug treatment, examining it within a century-long context of public and legal attitudes toward addiction. Karibo looks critically at all stages of the experiment: conception, execution, patient experience, external challenges. She includes voices of supporters and of critics.

Fundamentally, this book reveals how the United States—and Texas—has long struggled to understand its own attitudes about drug addiction. Do we blame or help those who become addicted? Do we focus on punitive policies or expanding social and medical services? What role do our prisons play?

These questions were already being asked 100 years ago, and we’re still waiting for answers.

The post Inside Fort Worth’s Narcotic Farm Experiment appeared first on www.texasobserver.org

News from the South - Texas News Feed

6-year-old boy survives near-drowning, witnesses angels in heaven

SUMMARY: On July 4, Krista Parker’s 6-year-old son, DJ, nearly drowned at Paragon Casino Resort in Louisiana. Despite DJ’s fear of water, he suddenly went lifeless by the pool. Krista and her husband performed CPR and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, eventually reviving him as water was expelled from his lungs. DJ was taken to Rapides Women’s and Children’s Hospital, where he recounted a near-death experience of seeing angels and God, strengthening his family’s faith. He now wants to be named Avir, meaning “air” in Hebrew, reflecting his experience. DJ suffered no lasting physical harm, emphasizing the importance of CPR training and water safety.

The post 6-year-old boy survives near-drowning, witnesses angels in heaven appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

KHOU 11 News Sports: LSU lands Brown, Astros swept

SUMMARY: The LSU Tigers have landed Lamar Brown, the top 2026 recruit and five-star defensive tackle from Baton Rouge, choosing LSU over Texas A&M, Miami, and Texas. In MLB, the Houston Astros swept the Dodgers in LA but were then swept at home by the Guardians, who had lost 10 straight games. Despite challenges, the Astros emphasize teamwork. College football returns as Houston Cougars aim for a Big 12 bounce-back under coach Willie Fritz, focusing on depth and competition. In tennis, Amanda Eissimova shocked the world by defeating the No. 1 player, Sebalana, to reach her first Grand Slam final at Wimbledon after overcoming burnout.

Here’s the latest on sports of interest for the Houston area. LSU signs Lamar Brown. Astros are swept. Cougars under Fritz.

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Why Kerr County balked on a new flood warning system

“Did fiscal conservatism block plans for a new flood warning system in Kerr County?” was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

In the week after the tragic July 4 flooding in Kerr County, several officials have blamed taxpayer pressure as the reason flood warning sirens were never installed along the Guadalupe River.

“The public reeled at the cost,” Kerr County Judge Rob Kelly told reporters one day after the rain pushed Guadalupe River levels more than 32 feet, resulting in nearly 100 deaths in the county, as of Thursday.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/024d0859980ef8978d239b5ed04ac727/0705%20Hill%20Country%20Flood%20RB%20TT%2094.jpg)

A community that overwhelmingly voted for President Donald Trump in 2016, 2020 and 2024, Kerr County constructed an economic engine on the allure of the Guadalupe River. Government leaders acknowledged the need for more disaster mitigation, including a $1 million flood warning system that would better alert the public to emergencies, to sustain that growth, but they were hamstrung by a small and tightfisted tax base.

An examination of transcripts since 2016 from Kerr County’s governing body, the commissioners court, offers a peek into a small Texas county paralyzed by two competing interests: to make one of the country’s most dangerous region for flash flooding safer and to heed to near constant calls from constituents to reduce property taxes and government waste.

“This is a pretty conservative county,” said former Kerr County Judge Tom Pollard, 86. “Politically, of course, and financially as well.”

County zeroes in on river safety in 2016

Cary Burgess, a local meteorologist whose weather reports can be found in the Kerrville Daily Times or heard on Hill Country radio stations, has noticed the construction all along the Guadalupe for the better part of the last decade.

More Texans and out-of-state residents have been discovering the river’s pristine waters lined with bald cypress trees, a long-time draw for camping, hiking and kayaking, and they have been coming in droves to build more homes and businesses along the water’s edge. If any of the newcomers were familiar with the last deadly flood in 1987 that killed 10 evacuating teenagers, they found the river’s threat easy to dismiss.

“They’ve been building up and building up and building up and doing more and more projects along the river that were getting dangerous,” Burgess recalls. “And people are building on this river, my gosh, they don’t even know what this river’s capable of.”

By the time the 1987 flood hit, the county had grown to about 35,000 people. Today, there are about 53,000 people living in Kerr County.

In 2016, Kerr County commissioners already knew they were getting outpaced by neighboring, rapidly growing counties on installing better flood warning systems and were looking for ways to pull ahead.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/506c5dbfd4d30784a0102a07ac66c42c/07171987%20Seagoville%20Bus.png)

During a March 28 meeting that year, they said as much.

“Even though this is probably one of the highest flood-prone regions in the entire state where a lot of people are involved, their systems are state of the art,” Commissioner Tom Moser said then. He discussed how other counties like Comal had moved to sirens and more modern flood warning systems.

“And the current one that we have, it will give – all it does is flashing light,” explained W.B. “Dub” Thomas, the county’s emergency management coordinator. “I mean all – that’s all you get at river crossings or wherever they’re located at.”

Kerr County already had signed on with a company that allowed its residents to opt in and get a CodeRED alert about dangerous weather conditions. But Thomas urged the commissioners court to strive for something more. Cell service along the headwaters of the Guadalupe near Hunt was spotty in the western half of Kerr County, making a redundant system of alerts even more necessary.

“I think we need a system that can be operated or controlled by a centralized location where – whether it’s the Sheriff’s communication personnel, myself or whatever, and it’s just a redundant system that will complement what we currently have,” Thomas said that year.

By the next year, officials had sent off its application for a $731,413 grant to FEMA to help bring $976,000 worth of flood warning upgrades, including 10 high water detection systems without flashers, 20 gauges, possible outdoor sirens, and more.

“The purpose of this project is to provide Kerr County with a flood warning system,” the county wrote in its application. “The System will be utilized for mass notification to citizens about high water levels and flooding conditions throughout Kerr County.”

But the Texas Division of Emergency Management, which oversees billions of FEMA dollars designed to prevent disasters, denied the application because they didn’t have a current hazard mitigation plan. They resubmitted it, news outlets reported, but by then, priority was given to counties that had suffered damage from Hurricane Harvey.

Political skepticism about a windfall

All that concern about warning systems seemed to fade over the next five years, as the political atmosphere throughout the county became more polarized and COVID fatigue frayed local residents’ nerves.

In 2021, Kerr County was awarded a $10.2 million windfall from the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, which Congress passed that same year to support local governments impacted by the pandemic. Cities and counties were given flexibility to use the money on a variety of expenses, including those related to storm-related infrastructure. Corpus Christi, for example, allocated $15 million of its ARPA funding to “rehabilitate and/or replace aging storm water infrastructure.” Waco’s McLennan County spent $868,000 on low water crossings.

Kerr County did not opt for ARPA to fund flood warning systems despite commissioners discussing such projects nearly two dozen times since 2016. In fact, a survey sent to residents about ARPA spending showed that 42% of the 180 responses wanted to reject the $10 million bonus altogether, largely on political grounds.

“I’m here to ask this court today to send this money back to the Biden administration, which I consider to be the most criminal treasonous communist government ever to hold the White House,” one resident told commissioners in April 2022, fearing strings were attached to the money.

“We don’t want to be bought by the federal government, thank you very much,” another resident told commissioners. “We’d like the federal government to stay out of Kerr County and their money.”

When it was all said and done, the county approved $7 million in ARPA dollars on a public safety radio communications system for the sheriff’s department and county fire services to meet the community’s needs for the next 10 years, although earlier estimates put that contract at $5 million. Another $1 million went to sheriff’s employees in the form of stipends and raises, and just over $600,000 went towards additional county positions. A new walking path was also created with the ARPA money.

While much has been made of the ARPA spending, it’s not clear if residents or the commissioners understood at the time they could have applied the funds to a warning system. Current Kerr County Judge Rob Kelly, and Thomas have declined repeated requests for interviews. Moser, who is no longer a commissioner, did not immediately respond to a Texas Tribune interview request.

Many Kerr County residents, including those who don’t normally follow every cog-turn of government proceedings, have now been poring over the county commissioners meetings this week including Ingram City Council member Raymond Howard. They’ve been digging into ARPA spending and other ways that the county missed opportunities to procure $1 million to implement the warning system commissioners wanted almost 10 years ago, and to prevent the devastating death toll from this week.

A week ago, Howard spent the early morning hours of July 4 knocking on neighbors’ doors to alert them to the flooding after he himself ignored the first two phone alerts on his phone in the middle of the night.

In the week since, the more he’s learned about Kerr County’s county inaction on a flood warning system, the angrier he has become.

“Well, they were obviously thinking about it because they brought it up 20 times since 2016 and never did anything on it,” Howard said, adding that he never thought to ask the city to install sirens previously because he didn’t realize the need for it. “I’m pretty pissed about that.”

Harvey Hilderbran, the former Texas House representative for Kerr County, said what he is watching play out in the community this week is what he’s seen for years in Texas: A disaster hits. There’s a rush to find out who’s accountable. Then outrage pushes officials to shore up deficiencies.

It’s not that Kerr County was dead set against making the area safer, Hilderbran said. Finding a way to pay for it is always where better ideas run aground, especially with a taxbase and leadership as fiscally conservative as Kerr’s.

“Generally everybody’s for doing something until it gets down to the details paying for it,” Hilderbran said. “It’s not like people don’t think about it … I know it’s an issue on their minds and something needs to be done.”

Howard, the 62-year-old Ingram city council member, came to Kerr County years ago to care for an ailing mother. Although he has now been diagnosed with stage four cancer, he said he intends to devote his life to make sure that his small two-mile town north of Kerrville has a warning system and he already knows where he’s going to put it.

“We’re going to get one, put it up on top of the tower behind the volunteer fire department,” he said. “It’s the thing I could do even if it’s the last thing I do …to help secure safety for the future.”

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2025/07/10/texas-kerr-county-commissioners-flooding-warning/.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

The post Why Kerr County balked on a new flood warning system appeared first on feeds.texastribune.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article presents a mostly factual and balanced overview of Kerr County’s flood warning system challenges within a politically conservative community. It highlights the county’s strong conservative stance on limited government spending and skepticism toward federal aid, reflecting typical right-leaning priorities such as fiscal conservatism and wariness of federal involvement. The coverage is careful to present multiple perspectives, including official statements and local residents’ concerns, without overt editorializing or ideological framing. The tone and content suggest an objective report focused on local governance dynamics rather than promoting a partisan agenda, though the conservative context is clearly emphasized.

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

The Center Square5 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Woman arrested in Morgantown McDonald’s parking lot

-

The Center Square7 days ago

Alcohol limits at odds in upcoming dietary guidelines | National

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Hill Country flooding: Here’s how to give and receive help

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Raleigh caps Independence Day with fireworks show outside Lenovo Center

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Shannon County Sheriff alleges ‘orchestrated campaign of harassment and smear tactics,’ threats to life

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

The Other Passionflower | Our Mississippi Home