Tambako the Jaguar/Moment via Getty Images

Anna Fagre, Colorado State University and Sadie Jane Ryan, University of Florida

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, humans had been the only species with reported cases of the disease. While early genetic analyses pointed to horseshoe bats as the evolutionary hosts of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, no reports had yet surfaced indicating it could be transmitted from humans to other animal species.

Less than two weeks later, a report from Belgium marked the first infection in a domestic cat – presumably by its owner. Summer 2020 saw news of COVID-19 outbreaks and subsequent cullings in mink farms across Europe and fears of similar calls for culling in North America. Humans and other animals on and around mink farms tested positive, raising questions about the potential for a secondary wildlife reservoir of COVID-19. That is, the virus could infect and establish a transmission cycle in a different species than the one in which it originated.

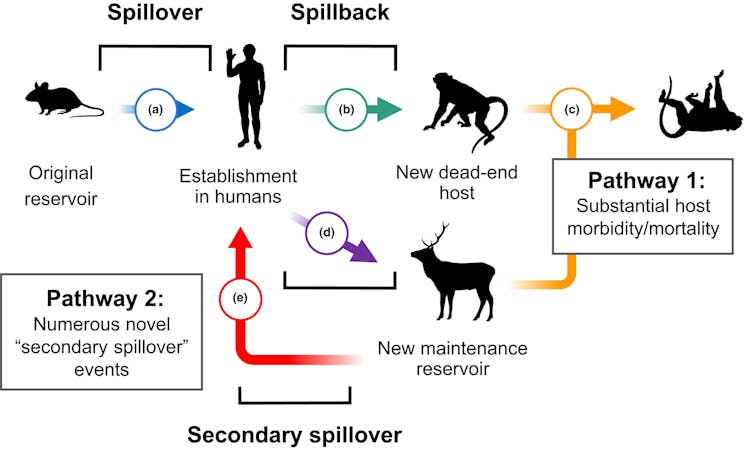

Researchers have documented this phenomenon of human-to-animal transmission, colloquially referred to as spillback or reverse zoonotic transmission, in both domestic and wild animals. Wildlife may be infected either directly from humans or indirectly from domestic animals infected by humans. This stepping-stone effect provides new opportunities for pathogens to evolve and can radically change how they spread, as seen with influenza and tuberculosis.

Fagre et al. 2022/Ecology Letters, CC BY-NC-ND

For example, spillback has been a long-standing threat to endangered great apes, even among populations with infrequent human contact. The chimpanzees of Gombe National Park, made famous by Jane Goodall’s work, have suffered outbreaks of measles and other respiratory diseases likely resulting from environmental persistence of pathogens spread by people living nearby or by ecotourists.

We are researchers who study the mechanisms driving cross-species disease transmission and how disease affects both wildlife conservation and people. Emerging outbreaks have underscored the importance of understanding how threats to wildlife health shape the emergence and spread of zoonotic pathogens. Our research suggests that looking at historical outbreaks can help predict and prevent the next pandemic.

Spillback has happened before

Our research group wanted to assess how often spillback had been reported in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. A retrospective analysis not only allows us to identify specific trends or barriers in reporting spillback events but also helps us understand where new emergent threats are most likely.

We examined historical spillback events involving different groups of pathogens across the animal kingdom, accounting for variations in geography, methods and sample sizes. We synthesized scientific reports of spillback across nearly a century prior to the COVID-19 pandemic – from the 1920s to 2019 – which included diseases ranging from salmonella and intestinal parasites to human tuberculosis, influenza and polio.

We were also interested in determining whether detection and reporting bias might influence what’s known about human-to-animal pathogen transmission. Charismatic megafauna – often defined as larger mammals such as pandas, gorillas, elephants and whales that evoke emotion in people – tend to be overrepresented in wildlife epidemiology and conservation efforts. They receive more public attention and funding than smaller and less visible species.

Complicating this further are difficulties in monitoring wild populations of small animals, as they decompose quickly and are frequently scavenged by larger animals. This drastically reduces the time window during which researchers can investigate outbreaks and collect samples.

Christopher Kimmel/Moment via Getty Images

The results of our historical analysis support our suspicions that most reports described outbreaks in large charismatic megafauna. Many were captive, such as in zoos or rehabilitation centers, or semi-captive, such as well-studied great apes.

Despite the litany of papers published on new pathogens discovered in bats and rodents, the number of studies examining pathogens transmitted from humans to these animals was scant. However, small mammals occupying diverse ecological niches, including animals that live near human dwellings – such as deer mice, rats and skunks – may be more likely to not only share their pathogens with people but also to be infected by human pathogens.

COVID-19 and pandemic flu

In our historical analysis of spillback prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the only evidence we found supporting the establishment of a human pathogen in a wildlife population were two 2019 reports describing H1N1 infection in striped skunks. Like coronaviruses, influenza A viruses such as H1N1 are adept at switching hosts and can infect a broad range of species.

Unlike coronaviruses, however, their widespread transmission is facilitated by migratory waterfowl such as ducks and geese. Exactly how these skunks became infected with H1N1 and for how long remains unclear.

Shortly after we completed the analysis for our study, reports describing widespread COVID-19 infection of white-tailed deer throughout North America began surfacing in November 2021. In some areas, the prevalence of infection was as high as 80% despite little evidence of sickness in the deer.

This ubiquitous mammal has effectively become a secondary reservoir of COVID-19 in North America. Further, genetic evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 evolves three times faster in white-tailed deer than in humans, potentially increasing the risk of seeding new variants into humans and other animals. There is already evidence of deer-to-human transmission of a previously unseen variant of COVID-19.

There are over 30 million white-tailed deer in North America, many in agricultural and suburban areas. Surveillance efforts to monitor viral evolution in white-tailed deer can help identify emerging variants and further transmission from deer populations into people or domestic animals.

Investigations into related species revealed that the risk of spillback varies. For instance, white-tailed deer and mule deer are highly susceptible to COVID-19 in the lab, while elk are not.

H5N1 and the US dairy herd

Since 2022, the spread of H5N1 has affected a broad range of avian and mammalian species around the globe – foxes, skunks, raccoons, opossums, polar bears, coyotes and seals, to name a few. Some of these populations are threatened or endangered, and aggressive surveillance efforts to monitor viral spread are ongoing.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported the presence of H5N1 in the milk of dairy cows. Genetic analyses point to an introduction of the virus into cows as early as December 2023, probably in the Texas Panhandle. Since then, it has affected 178 livestock herds in 13 states as of August 2024.

How the virus got into dairy cow populations remains undetermined, but it was likely by migratory waterfowl infected with the virus. Efforts to delineate exactly how the virus moves among and between herds are underway, though it appears contaminated milking equipment rather than aerosol transmission, may be the culprit.

Jacob Wackerhausen/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Given the ability of influenza A viruses such as avian flu to infect a broad range of species, it is critical that surveillance efforts target not only dairy cows but also animals living on or around affected farms. Monitoring high-risk areas for cross-species transmission, such as where livestock, wildlife and people interact, provides information not only about how widespread a disease is in a given population – in this case, dairy cows – but also allows researchers to identify susceptible species that come into contact with them.

To date, H5N1 has been detected in several animals found dead on affected dairy farms, including cats, birds and a raccoon. As of August 2024, four people in close contact with infected dairy cows have tested positive, one of whom developed respiratory symptoms. Other wildlife and domestic animal species are still at risk. Similar surveillance efforts are underway to monitor H5N1 transmission from poultry to humans.

Humans are only 1 part of the network

The language often used to describe cross-species transmission fails to encapsulate its complexity and nuances. Given the number of species that have been infected with COVID-19 throughout the pandemic, many scientists have called for limiting the use of the terms spillover and spillback because they describe the transmission of pathogens to and from humans. This suggests that disease and its implications begin and end with humans.

Considering humans as one node in a large network of transmission possibilities can help researchers more effectively monitor COVID-19, H5N1 and other emerging zoonoses. This includes systems-thinking approaches such as One Health or Planetary Health that capture human interdependence with the health of the total environment.

Anna Fagre, Veterinary Microbiologist and Wildlife Epidemiologist, Colorado State University and Sadie Jane Ryan, Professor of Medical Geography, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.