gilaxia/E+ via Getty Images

Dawn Rogala, Smithsonian Institution and Gwénaëlle Kavich, Smithsonian Institution

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

How is paint made? – Atharva, age 11, Bengaluru, India

Did you ever mix dirt and water when you were playing outside? You made a paint. Did you draw shapes on the ground with your muddy hands? You made a painting.

Paint is made by combining a colorful substance – a pigment – with another material that binds the color together and helps spread that color onto surfaces such as paper, fabric or wood. Pigments can be found everywhere – in rocks and minerals, plants or insects. Some colors are made by scientists in laboratories.

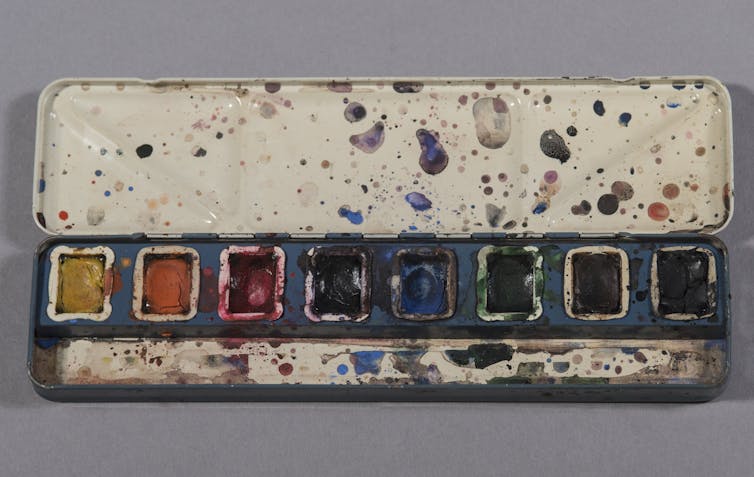

Long ago, artists made their own paints by mixing pigments with natural materials such as water, oil or egg yolk to hold the colors together in a paste. Artists today can still make their own paints, or they can order them from factories that mix, package and ship paint all over the world. Paint companies use large, industrial machines to grind pigments and binders together; these commercial paints include synthetic materials and preservatives to control the paint’s behavior and to help paint last longer in tubes or cans.

Paints and coatings do many jobs beyond just coloring paper in an artist’s studio. They are also used as protective coatings to shield houses and cars from the sun or the cold, or as a barrier between boats and the water that surrounds their wood, metal or plastic parts. Where and how a paint will be used influence how it’s made and with what ingredients.

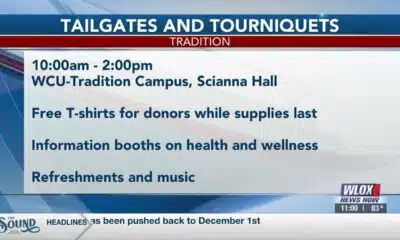

Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of David Driskell, CC BY

Choosing the right materials

A lot of questions need to be answered before materials are chosen for a paint.

- Who will use the paint? An artist, a house painter, an armadillo, a robot at an assembly plant?

- Why is the paint being used? For museum paintings and sculptures? In designs for furniture or mailboxes?

- How will the paint be applied? By brush, by spray, or some other way?

- Where and when will the paint be used? Does it need to dry quickly or slowly? Will the painted surface get really cold or hot? Is the paint safe for kids to use at home or school?

- What should the paint look like? Should the dried paint be shiny or matte? Should the surface be lumpy, or should it flatten and level out? Should the colors be bright or dull? Should the paint layers be opaque, transparent or almost clear? Does the paint need to hold up against scuffs and stains?

There are many different companies that design and make the wide range of paints used around the world for all these various applications. Experts at each manufacturer understand their special type of paint, how the paint materials are measured and mixed, and the best ways to store and apply the paint. A single factory can make tens of thousands of gallons of paint each day, and paint companies produce millions of tubes of paint every year.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Miss Ruth B. Moran

Using paint to learn about the past

We work at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, where we study and conserve the diverse collection of painted objects at the Smithsonian – from planes and spacecraft to portraits of presidents and maps covered in abstract swirls of color. Bright coatings are part of everything from the painted clothing and cultural items of Native peoples to the pots and pans used by chef Julia Child.

Art conservators and conservation scientists like us work together to study and preserve cultural heritage such as paintings and painted objects. Studying paint helps us learn about the past and protect this history for future generations.

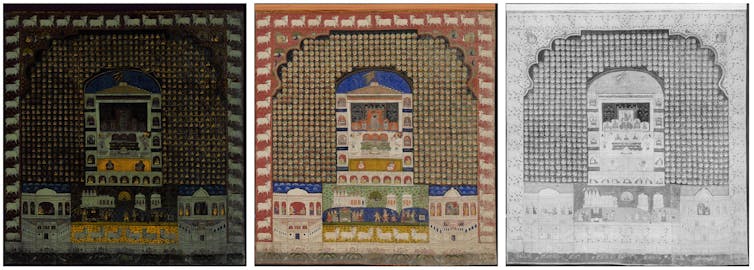

The paint colors used on large, traditional Indian paintings called “pichwai,” for example, include pigments gathered from around the world. They can reveal information about ancient manufacturing and how communities that lived far apart exchanged goods and knowledge.

There are many techniques to investigate artwork, from looking at small pieces of paint under a microscope to using more complicated equipment to analyze materials exposed to different types of energy. For example, we can use X-ray, infrared or ultraviolet imaging to identify different pigments in a painting.

National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Karl B. Mann, S1992.28, Department of Conservation and Scientific Research, Orthomosaics and UV Fluorescence

Research on an Alaskan Tlingit crest hat made in the 1800s looked at the molecules in paint binders, combined with 3D scanning, to help clan members replicate the hat for ceremonial use.

Unusual uses bring conservation challenges

Artists use all sorts of materials in their artwork that were designed for other purposes. Some 19th- and early 20th-century sculptures were painted with laundry bluing – a material that used blue pigment to brighten clothes during washing. In the 1950s, artists started using thin, quick-drying house paint in their paintings.

When paints are used in a way that was not part of their design, strange things can happen. Paints made to be applied in thin layers but instead are used in thick layers can wrinkle and pucker as they dry. Paints designed to stick to rough wood can curl or lift away from slick surfaces. The colors and ingredients in paint can also fade or darken over time. Some artists want these different effects in their artwork; some artists are surprised when paints don’t behave the way they expected.

Art conservators and conservation scientists use information about artists and their paints to understand why artworks are faded, broken or acting in surprising ways, and they use that knowledge to slow or stop the damage. We can even clean some kinds of damage with lasers.

The more we know about paint, the more we learn about the past lives of painted objects and how to keep those objects around for a long, long time.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Dawn Rogala, Paintings Conservator and Program Manager, Smithsonian Institution and Gwénaëlle Kavich, Conservation Scientist, Smithsonian Institution

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.