News from the South - Texas News Feed

City of Austin honors community advocate after passing, declares March 7 ‘Heath Donell Creech Day’

SUMMARY: On March 7, the City of Austin declared “Heath Donell Creech Day” to honor the late community leader, who passed away at 57 on February 24. Creech founded the African American Leadership Institute (AALI) and Soulciti, a platform highlighting black culture in Central Texas. Attendees, including local representatives, recognized his contributions at a memorial that launched “The House That Heath Built,” an exhibit showcasing his impactful leadership and initiatives. The event emphasized Creech’s legacy and the ongoing need to amplify black voices in the community, alongside the introduction of a dedicated website to commemorate his work.

The post City of Austin honors community advocate after passing, declares March 7 ‘Heath Donell Creech Day’ appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

The History of Eugenics in Texas Isn’t What You Think

I’ll admit: Having grown addicted to the treats of literary nonfiction, I don’t make it through too many academic histories these days. If I’m going to, there’d better at least be a decent lede—and the Marxian opening to a new history of the eugenics movement in Texas fits the bill.

“Monsters haunted the imaginations of some of the most educated white Texans from the 1850s to the dawn of World War II,” tees off The Purifying Knife: The Troubling History of Eugenics in Texas, a 300-page (endnotes included) work by husband-wife historians Michael Phillips and Betsy Friauf.

Philips, who recently retired from a teaching position at the University of North Texas in Denton, previously authored White Metropolis, a well-regarded history of race in Dallas.

The new book, out June 3 from University of Oklahoma Press, unearths a cast of unsavory Texas characters who pushed eugenics—the discredited pseudoscientific belief that the human species should be improved through practices such as forced sterilization—from the mid-19th century through the 1930s. In the latter decades of that period, the majority of U.S. states enacted forced-sterilization laws that targeted the non-white and the disabled, leading to more than 60,000 coerced operations. But Texas, perhaps surprisingly, never passed such a law.

“Although a violent and white supremacist place, Texas remained on the sideline during this particular American carnage,” the authors write. The reasons why are the book’s most interesting subject.

Though the Lone Star State ultimately resisted eugenics, it was home to early pioneers. A Georgia-Texas transplant, Gideon Lincecum was a botanist and surgeon who “one day in the 1850s took it upon himself to castrate an alcohol-dependent patient in Texas, an assault he said cured his involuntary test subject’s addiction.” Lincecum did so before the term eugenics had even been coined, and he became one of the earliest advocates of treating humans more like a breeder treats horses or dogs. Lincecum managed to get the nation’s first forced-sterilization bill put before the Texas Legislature in 1853. But Lincecum, much too far ahead of his time, saw the bill fizzle amid “copious mockery.”

F.E. Daniel, another physician and editor of the Texas Medical Journal from the 1880s until the 1910s, pushed for forced vasectomy and hysterectomy to assure Anglo-Saxon dominance, the book’s authors report. Daniel “embodied the values of the southern Progressive movement,” a particular turn-of-the-century brew that mixed scientific rationalism with rank racism. Eugenicists also made inroads at Texas universities, particularly UT-Austin and Rice.

But Progressives and egghead professors were poor messengers in a state where politicians like “Pa” and “Ma” Ferguson stoked right-wing populist prejudice against government and academic elites—and where religious fundamentalism was a rising political power. Eugenicist proposals, whether focused on sterilization or restricting who could marry, continued to fail.

“Attacks on colleges and universities, therefore, provided the unintentional benefit of shielding the poor and politically powerless in Texas from a horrifying, widely shared elite agenda that prevailed elsewhere,” the authors write. In fact, liberal California was the nation’s eugenic epicenter, where deference to academic expertise helped fuel the largest number of forced sterilizations among states—a practice continued through 1980.

Further frustrating the Texas eugenicists, a large portion of the state’s capitalists depended on cheap Mexican labor and weren’t going to forsake their bottom lines over abstract concerns about race-mixing. John Box, an East Texas Congressman, attempted to overcome these employers when federal lawmakers passed the deeply racist Immigration Act of 1924, which sought to halt immigration from Asia and Eastern and Southern Europe. Box pushed for a cap on Mexican immigration, too, but the Western Hemisphere was ultimately exempted.

“To the wealthy landowners exploiting migrant labor, the threat of paying higher wages proved far more frightening than any dysgenic nightmare that Box and his allies could conjure,” the authors write.

Ultimately, the combination of greedy capitalists, right-wing anti-intellectualism, and solidifying religious opposition (Catholics grew rapidly in Texas during these decades, and the Vatican explicitly opposed forced sterilization in 1930) doomed eugenicist legislation that was considered in Austin between the 1850s and the 1930s. In an email to the Observer, Philips called this “a unique alignment that led one set of bad ideas … to defeat another malign worldview.” Soon, the eugenics movement began its fall from grace nationwide as the discovery of Hitler’s concentration camps generally tarnished proposals for racial engineering.

The history laid out in this book could tempt one to reassess today’s right-wing populist attacks on academia. Perhaps these, too, could end up being right for the wrong reasons. But Philips doesn’t think so.

He attributes universities’ erstwhile embrace of eugenics to higher education’s status as “almost universally white, straight, American-born, male, and wealthy.” More diverse scholarly bodies would have likely eschewed such ideas; a Jewish anthropologist, Franz Boas, eventually did help puncture the movement’s pseudoscience, for example. “That’s why the attacks [today] on diversity, equity, and inclusion today are so dangerous,” Philips wrote the Observer. “It threatens to make universities more like they were at the time eugenics became widely accepted wisdom.”

The book takes a pass through more recent figures trying to revive race science in America, like Charles Murray and Richard Spencer, and the authors also highlight the eugenics-adjacent rhetoric of today’s rabidly xenophobic politicians—namely the U.S. president and the governor of Texas. A bit more provocatively, they tie threads between eugenics and the current fight over abortion. While some on the right make hay of the historic ties between eugenics and early advocates for reproductive rights, the authors take another tack by focusing on the power allowed or disallowed to the state.

“The battle over the right of the state to control reproduction once centered on preventing children labeled as dysgenic from being born. By 2023, the state decided it could force women to give birth even when the child had no chance of survival,” they write. “The two great battles in Texas over government power and bodily integrity since the 1850s, eugenics and abortion, had very different outcomes.”

The post The History of Eugenics in Texas Isn’t What You Think appeared first on www.texasobserver.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content critically examines historical and contemporary issues linked to eugenics, racial discrimination, and right-wing populism, emphasizing the negative impact of these ideologies and highlighting progressive critiques such as the dangers of attacks on diversity and inclusion. While it acknowledges complexities within politics and history, the article leans toward a center-left perspective by focusing on social justice, systemic racism, and the defense of academic and reproductive freedoms.

News from the South - Texas News Feed

LIST: Top priority cold homicide cases Texas Rangers are still trying to solve

SUMMARY: The Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) is investigating over 145 unsolved homicides, with 13 prioritized cases involving victims from children to adults. These cold cases span decades and regions in Texas, including Dallas, Houston, Universal City, Lubbock, and more. Notable cases include 7-year-old Elizabeth Lynne Barclay, missing and murdered in 1979, and the 1980 Christmas Day murders of Estella and Andrew Salinas in Houston. Other cases involve victims like Yolanda Herrera (1981), Richard Garza (1984), and Marianne Wilkinson (2007), each with unresolved circumstances. Texans can submit tips to the Texas Rangers or Crime Stoppers for assistance in solving these cases.

The post LIST: Top priority cold homicide cases Texas Rangers are still trying to solve appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Responders from Mexico help with Texas flood response

SUMMARY: Responders from Mexico are assisting Texas in flood recovery along the Guadalupe River. A team of about 45 rescuers from Nuevo Leon, equipped with boats, ATVs, drones, and search dogs, volunteered to aid Kerr County after catastrophic floods. Eric Cavazos, director of Mexico’s Civil and Emergency Response Agency, emphasizes that their help is driven by humanity, not politics. The team’s search and rescue work has been vital, marking key locations and locating missing persons. Despite the emotional challenges, including finding personal items like a teddy bear, the Mexican responders are committed to continuing the mission until all those missing are found.

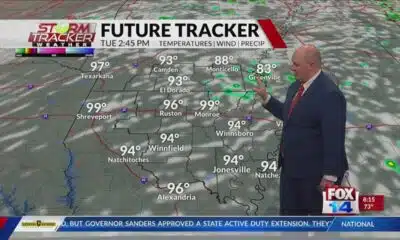

Dallas-Fort Worth news and weather from the FOX 4 weekend team.

Subscribe to FOX 4: https://www.youtube.com/fox4news?sub_confirmation=1

Dallas news, weather, sports and traffic from KDFW FOX 4, serving Dallas-Fort Worth, North Texas and the state of Texas.

Download the FOX LOCAL app: fox4news.com/foxlocal

Watch FOX 4 Live: https://www.fox4news.com/live

Download the FOX 4 News App: https://www.fox4news.com/apps

Download the FOX 4 WAPP: https://www.fox4news.com/apps

Follow FOX 4 on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Fox4DFW/

Follow FOX 4 on Twitter: https://twitter.com/FOX4

Follow FOX 4 on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/fox4news/

Subscribe to the FOX 4 newsletter: https://www.fox4news.com/newsletters

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Learning loss after Helene in Western NC school districts

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Turns out, Medicaid was for us

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed1 day ago

Bread sold at Walmart, Kroger stores in TN, KY recalled over undeclared tree nut

-

Local News7 days ago

“Gulfport Rising” vision introduced to Gulfport School District which includes plan for on-site Football Field!

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

The Bayeux Tapestry will be displayed in the UK for the first time in nearly 1,000 years

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

With brand new members, Louisiana board votes to oust local lead public defenders

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

Why Kerr County balked on a new flood warning system