Strengthening relationships strengthens communities, which influences societies.

Liza M. Hinchey, Wayne State University

Political chasms, wars, oppression … it’s easy to feel hopeless and helpless watching these dark forces play out. Could any of us ever really make a meaningful difference in the face of so much devastation?

Given the scale of the world’s problems, it might feel like the small acts of human connection and solidarity that you do have control over are like putting Band-Aids on bullet wounds. It can feel naive to imagine that small acts could make any global difference.

As a psychologist, human connection researcher and audience member, I was inspired to hear musician Hozier offer a counterpoint at a performance this year. “The little acts of love and solidarity that we offer each other can have powerful impact … ” he told the crowd. “I believe the core of people on the whole is good – I genuinely do. I’ll die on that hill.”

I’m happy to report that the science agrees with him.

Research shows that individual acts of kindness and connection can have a real impact on global change when these acts are collective. This is true at multiple levels: between individuals, between people and institutions, and between cultures.

This relational micro-activism is a powerful force for change – and serves as an antidote to hopelessness because unlike global-scale issues, these small acts are within individuals’ control.

A personal connection makes you more willing to find common ground.

Abstract becomes real through relationships

Theoretically, the idea that small, interpersonal acts have large-scale impact is explained by what psychologists call cognitive dissonance: the discomfort you feel when your actions and beliefs don’t line up.

For example, imagine two people who like each other. One believes that fighting climate change is crucial, and the other believes that climate change is a political ruse. Cognitive dissonance occurs: They like each other, but they disagree. People crave cognitive balance, so the more these two like each other, the more motivated they will be to hear each other out.

According to this model, then, the more you strengthen your relationships through acts of connection, the more likely you’ll be to empathize with those other individual perspectives. When these efforts are collective, they can increase understanding, compassion and community in society at large. Issues like war and oppression can feel overwhelming and abstract, but the abstract becomes real when you connect to someone you care about.

So, does this theory hold up when it comes to real-world data?

Small acts of connection shift attitudes

Numerous studies support the power of individual acts of connection to drive larger-scale change.

For instance, researchers studying the political divide in the U.S. found that participants self-identifying as Democrats or Republicans “didn’t like” people in the other group largely due to negative assumptions about the other person’s morals. People also said they valued morals like fairness, respect, loyalty and a desire to prevent harm to others.

I’m intentionally leaving out which political group preferred which traits – they all sound like positive attributes, don’t they? Even though participants thought they didn’t like each other based on politics, they also all valued traits that benefit relationships.

One interpretation of these findings is that the more people demonstrate to each other, act by act, that they are loyal friends and community members who want to prevent harm to others, the more they might soften large-scale social and political disagreements.

Even more convincingly, another study found that Hungarian and Romanian students – people from ethnic groups with a history of social tensions – who said they had strong friendships with each other also reported improved attitudes toward the other group. Having a rocky friendship with someone from the other group actually damaged attitudes toward the other ethnic group as a whole. Again, nurturing the quality of relationships, even on an objectively small scale, had powerful implications for reducing large-scale tensions.

In another study, researchers examined prejudice toward what psychologists call an out-group: a group that you don’t belong to, whether based on ethnicity, political affiliation or just preference for dogs versus cats.

They asked participants to reflect on the positive qualities of someone they knew, or on their own positive characteristics. When participants wrote about the positive qualities of someone else, rather than themselves, they later reported lower levels of prejudice toward an out-group – even if the person they wrote about had no connection to that out-group. Here, moving toward appreciation of the other, rather than away from prejudice, was an effective way to transform preconceived beliefs.

So, small acts of connection can shift personal attitudes. But can they really affect societies?

From one-on-one to society-wide

Every human being is embedded in their own network with the people and world around them, what psychologists call their social ecology. Compassionate change at any level of someone’s social ecology – internally, interpersonally or structurally – can affect all the other levels, in a kind of positive feedback loop, or upward spiral.

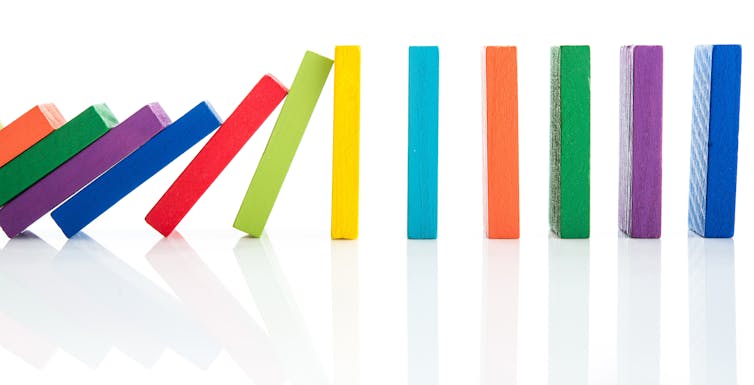

For instance, both system-level anti-discrimination programming in schools and interpersonal support between students act reciprocally to shape school environments for students from historically marginalized groups. Again, individual acts play a key role in these positive domino effects.

Small positive steps can build off each other in a chain reaction.

Even as a human connection researcher, I’ve been surprised by how much I and others have progressed toward mutual understanding by simply caring about each other. But what are small acts of connection, after all, but acts of strengthening relationships, which strengthen communities, which influence societies?

In much of my clinical work, I use a model called social practice — or “intentional community-building” – as a form of therapy for people recovering from serious mental illnesses, like schizophrenia. And if intentional community-building can address some of the most debilitating states of the human psyche, I believe it follows that, writ large, it could help address the most debilitating states of human societies as well.

Simply put, science supports the idea that moving toward each other in small ways can be transformational. I’ll die on that hill too.

Liza M. Hinchey, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Psychology, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.