Zinkevych/iStock via Getty Images

Chirag Shah, University of Washington

If you have used Google lately and been lucky – or unlucky – enough to encounter an answer to your query rather than a bunch of links, you have been subjected to something called AI Overviews. This is a new core feature that Google has been rolling out, a move widely anticipated since the company’s experiments with its LaMDA large language model in 2021, and since OpenAI’s ChatGPT artificial intelligence chatbot rocketed to prominence in 2023.

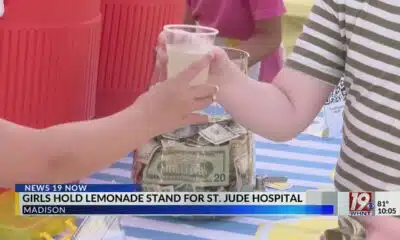

Screen capture by The Conversation, CC BY-ND

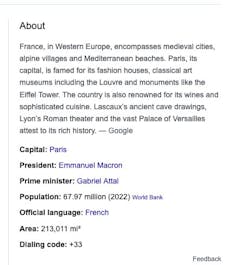

This feature is yet another addition to the increasing number of add-ons and tools being integrated into search engines like Google. Some of the notable examples include knowledge graph-driven knowledge panels, which are used to populate relevant factual information in an infobox next to search results, and featured snippets, which are blurbs excerpted from a search result and provided before the link to that page.

But what’s different about AI Overviews is that they are not simply extracted from relevant sources but generated behind the scenes by Google’s generative AI technology. The company’s goal is to give you a personalized, on-demand answer instead of a standard set of documents or even an answer box matching your query.

This seems almost magical and potentially useful in many situations. After all, people use search engines primarily to find answers and not lists of documents. But there’s more to the picture.

My colleague Emily Bender and I have written about what search engine users need, want and have. We have shown that they want not only information but also the ability to discover, learn and question what they find. In other words, users have a wide range of situations and objectives, and compressing them down to a set of links or, worse, a single answer is problematic.

Bad advice

These AI features vacuum up information from the internet and other available sources and spit out an answer based on how they are trained to associate words. A core argument against them is that they mostly remove from the equation the user’s judgment, agency and opportunity to learn.

This may be OK for many searches. Want a description of how inflation has affected grocery prices in the past five years, or a summary of what the European Union AI Act includes? AI Overviews can be a good way to cut through a lot of documents and extract those specific answers.

But people’s searching needs don’t end with factual information. They look for ideas, opinions and advice. Looking for suggestions about how to keep the cheese from sliding off your pizza? Google will tell you that you should add some glue to the sauce. Or wondering if running with scissors has any health benefits? Sure, Google will say, “it can also improve your pores and give you strength”.

While a reasonable user can understand that such outrageous answers are likely to be wrong, it’s hard to detect that for factual questions.

For example, while researching the faith of U.S. presidents, Google’s AI Overviews gave the incorrect answer that Barack Obama is a Muslim. This misinformation was widely circulated and debunked years ago, but Google regurgitated it with no good way for users to learn that it is misinformation.

What about a student using Google for homework and asking which countries in Africa start with the letter K? While Kenya does meet this criteria, Google’s AI Overviews incorrectly answered that there are no such countries.

Google has acknowledged issues with AI Overviews and said it has addressed them. But the concern remains: Can you really trust any answers you receive through this service?

How to avoid AI answers

There are alternatives. You can always go back to the traditional Google search with its 10 blue links. Click on “More” in the menu – All, News, Images, Maps, Videos and More – directly below the search field at the top of the Google search page and select “Web.”

You can then do what you have likely done for decades now – sift through some of the top results, visit a few of those sites and decide for yourself. It does take a little work, but it gives you back the ability to examine multiple sites and evidence to support or refute something. More importantly, you leave open the possibilities for learning, discovery and serendipity.

AI Overviews is like fast food that gets delivered through a drive-through window – it’s quick, hot and convenient, but not the healthiest choice. Going through Google’s traditional search results is like examining a menu in a sit-down restaurant and placing an order that will take awhile to make it to your table. You can ask your server questions about those items and even request some changes to the restaurant’s offerings. It’s prepared with more care, customization and control, but also takes longer and may cost more.

These aren’t the only methods of finding information, however. There are alternatives to Google’s search engine, including specialty search tools.

For scholarly needs, Google Scholar, Semantic Scholar and CORE are helpful places to look for research papers and citations. Looking for medical information? Try PubMed, ScienceDirect and OpenMD. For legal needs, some services include Fastcase, Caselaw Access Project and CourtListener.

Concerned about privacy? Check out DuckDuckGo, Startpage and Swisscows. If you still want AI-generated answers, some of the alternatives to Google’s AI Overviews and rival Bing’s Copilot are You.com and Komo, which provide more transparency about the data they collect about you, provide greater privacy and also offer ways to opt out of having your data collected for training their AI models.

A balanced information diet

Perhaps you can’t afford to eat out at a nice restaurant or prepare every meal from scratch every time, but it’s important to avoid ending up going through a drive-through for all your nourishment. After all, you are what you eat, and in a similar vein, you are how you search.

It’s easy to fall for sensational headlines and bite-size news that lack context. But you don’t have to let that define you. You can expand the scope of how you search. It’s OK to hit the drive-through every now and then and go for AI Overviews, but it’s important to also find other more wholesome ways to fulfill your needs – for food and for information.

Chirag Shah, Professor of Information Science, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.