The Conversation Weekly - Podcast

Jewish doctors in the Warsaw Ghetto secretly documented the effects of Nazi-imposed starvation, and the knowledge is helping researchers today – podcast

Jewish doctors in the Warsaw Ghetto secretly documented the effects of Nazi-imposed starvation, and the knowledge is helping researchers today – podcast

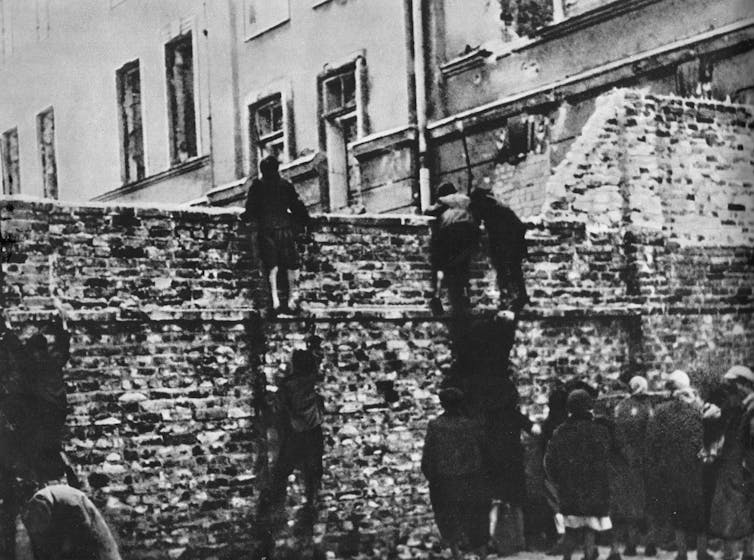

Blid Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Daniel Merino, The Conversation

During the years of suffering and tragedy that defined the Warsaw Ghetto in the midst of World War II, a team of Jewish doctors secretly documented the effects of starvation on the human body when the Nazis severely limited the amount of food available in the Jewish ghetto. The doctors collected this work in a book and, 80 years later, Merry Fitzpatrick rediscovered the brave efforts of these doctors hidden in a library at Tufts University, in Massachusetts in the U.S. In this Discovery episode of The Conversation Weekly, we speak to Fitzpatrick about how she found this piece of history, the story of its creation and how modern scientists are learning from the knowledge so bravely documented by the Jewish doctors.

Merry Fitzpatrick is an assistant professor at Tufts University who studies food security and malnutrition, especially in conflict zones. One day, she was searching through the school library and came across a book that she had never heard of in the basement.

“I went and pulled it off the shelf, and it was this crumbling little book. Its pages were just brown and brittle, and you could tell it hadn't been opened in a long time,” she says. The foreword described the conditions of the Warsaw Ghetto and the anguish of doing research there. It was written by Israel Milejkowski, who Fitzpatrick calls the “Fauci of the ghetto”, after the former chief medical advisor to the U.S. president Anthony Fauci.

nieznany/unknown via Wikimedia Commons

Over the course of 1941 and 1942, Milejkowski and his colleagues saw an opportunity to produce something good from the horrors of the Nazi-controlled ghetto. The lack of food was extreme. “The Jews were given a ration of 180 calories a day at one point. That's like half a cookie,” says Fitzpatrick. As the doctors took care of the Jewish population in the ghetto – including their friends and colleagues – they documented the effects of starvation, too. These doctors then collected their research into the book that Fitzpatrick found.

Even today, the research done by the Jewish doctors is shedding light on some mysteries within the field of starvation and malnutrition research. Tuberculosis was very common in the ghetto, but when the doctors would test starving children with obvious symptoms of tuberculosis, the tests would often come back negative. As Fitzpatrick explains, “What it was was that in starvation, the body pretty much gives up on immunity – that's not the priority. So when you do a test, you're looking for an immune response that isn't there.”

To find out how this idea is helping Fitzpatrick better understand HIV in malnourished children and the rest of Milejkowski's story, tune in to this week's episode of The Conversation Weekly.

This episode was produced by Mend Mariwany and hosted by Dan Merino. The executive producer is Mend Mariwany. Eloise Stevens does our sound design, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find the original story written by Merry Fitzpatrick and her colleague Irwin Rosenberg on The Conversation.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also sign up to The Conversation's free daily email here. A transcript of this episode will be available soon.

Listen to “The Conversation Weekly” via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

Daniel Merino, Associate Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Podcasts

Cloud seeding can increase rain and snow, and new techniques may make it a lot more effective – podcast

Cloud seeding can increase rain and snow, and new techniques may make it a lot more effective – podcast

John Finney Photography/Moment via Getty Images

Daniel Merino, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, The Conversation

When an unexpected rainstorm leaves you soaking wet, it is an annoyance. When a drought leads to fires, crop failures and water shortages, the significance of weather becomes vitally important.

If you could control the weather, would you?

Small amounts of rain can mean the difference between struggle and success. For nearly 80 years, an approach called cloud seeding has, in theory, given people the ability to get more rain and snow from storms and make hailstorms less severe. But only recently have scientists been able to peer into clouds and begin to understand how effective cloud seeding really is.

In this episode of “The Conversation Weekly,” we speak with three researchers about the simple yet murky science of cloud seeding, the economic effects it can have on agriculture, and research that may allow governments to use cloud seeding in more places.

Katja Friedrich, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder in the U.S., is a leading researcher on cloud seeding. “When we do cloud seeding, we are looking for clouds that have tiny super-cooled liquid droplets,” she explains. Silver iodide is very similar in structure to an ice crystal. When the droplets touch a particle of silver iodide, “they freeze, then they can start merging with other ice crystals, become snowflakes and fall out of the cloud.”

While the process is fairly straightforward, measuring how effective it is in the real world is not, according to Friedrich. “The problem is that once we modify a cloud, it's really difficult to say what would've happened if you hadn't cloud-seeded.” It's hard enough to predict weather without messing with it artificially.

Zuckerle/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

In 2017, Friedrich's research group had a breakthrough in measuring the effect of cloud seeding. “We flew some aircraft, released silver iodide and generated these clouds that were like these six exact lines that were downstream of where the aircraft were seeding,” she says. They then had a second aircraft fly through the clouds. “We could actually quantify how much snow we could produce by two hours of cloud seeding.” That effect, according to research on cloud seeding, is an increase in precipitation of somewhere around 5% to 20% or 30%, depending on conditions.

Measuring the effect on precipitation – whether rain or snow – directly may have taken complex science and a bit of luck, but in places that have been using cloud seeding for long periods of time, the economic benefits are shockingly clear.

Dean Bangsund is a researcher at North Dakota State University who studies the economics of agriculture. “We have a high amount of hail damage in North Dakota,” said Bangsund. For decades, the state government has been using cloud seeding to reduce hail damage, as cloud seeding leads to the formation of more pieces of smaller hail compared to fewer pieces of larger hail. “It doesn't 100% eliminate hail; it's designed to soften the impact.”

Every 10 years, the state of North Dakota does an analysis on the economic impacts of the cloud seeding program, measuring both reduction in hail damage and benefits from increased rain. Bangsund led the last report and says that for every dollar spent on the cloud seeding program, “we are looking at something that is anywhere from $8 or $9 in benefit on the really lowest scale, up to probably $20 of impact per acre.” With millions of acres of agricultural fields in the cloud seeding area, that is a massive economic benefit.

Both Freidrich and Bangsund emphasized that cloud seeding, while effective in some cases, cannot be used everywhere. There is also a lot of uncertainty in how much of an effect it has. One way to improve the effectiveness and applicability of cloud seeding is by improving the seed. Linda Zou is a professor of civil infrastructure and environmental engineering at Khalifa University in the United Arab Emirates.

Her work has focused on developing a replacement for silver iodide, and her lab has developed what she calls a nanopowder. “I start with table salt, which is sodium chloride,” says Zou. “This desirable-sized crystal is then coated with a thin nanomaterial layer of titanium dioxide.” When salt gets wet, it melts and forms a droplet that can efficiently merge with other droplets and fall from a cloud. Titanium dioxide attracts water. Put the two together and you get a very effective cloud-seeding material.

From indoor experiments, Zou found that “with the nanopowders, there are 2.9 times the formation of larger-size water droplets.” These nanopowders can also form ice crystals at warmer temperatures and less humidity than silver iodide.

As Zou says, “if the material you are releasing is more reactive and can work in a much wider range of conditions, that means no matter when you decide to use it, the chance of success will be greater.”

This episode was written and produced by Katie Flood. Mend Mariwany is the executive producer of The Conversation Weekly. Eloise Stevens does our sound design, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation's free daily email here.

Listen to “The Conversation Weekly” via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

Daniel Merino, Associate Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, Science + Technology Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Podcasts

Three AI experts on how access to ChatGPT-style tech is about to change our world – podcast

Three AI experts on how access to ChatGPT-style tech is about to change our world – podcast

ktsimage via Canva

Daniel Merino, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, The Conversation

ChatGPT burst onto the technology world, gaining 100 million users by the end of January 2023, just two months after its launch and bringing with it a looming sense of change.

The technology itself is fascinating, but part of what makes ChatGPT uniquely interesting is the fact that essentially overnight, most of the world gained access to a powerful generative artificial intelligence that they could use for their own purposes. In this episode of The Conversation Weekly, we speak with researchers who study computer science, technology and economics to explore how the rapid adoption of technologies has, for the most part, failed to change social and economic systems in the past – but why AI might be different, despite its weaknesses.

Spending just a few minutes playing with new, generative AI algorithms can show you just how powerful they are. You can open up Dall-E, type in a phrase like “dinosaur riding motorcycle across a bridge,” and seconds later, the algorithm will produce multiple images more or less depicting what you asked for. ChatGPT does much the same, just with text as its output.

The Conversation/OpenAI, CC BY-ND

These models are trained on huge amounts of data taken from the internet, and as Daniel Acuña, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in the U.S. explains, that can be a problem. “If we are feeding these models data from the past and data from today, they will learn some biases,” Acuña says. “They will relate words – let's say about occupations – and find relationships between words and how they are used with certain genders or certain races.”

The problem of bias in AI is not new, but with increased access, more people are now using it, and as Acuña says, “I hope that whoever is using those models is aware of these issues.”

With any new technology there is always a risk of misuse, but these concerns are usually accompanied by hope that as people gain access to better tools, their lives will improve. That theory is exactly what Kentaro Toyama, a professor of community information at the University of Michigan, has studied for nearly two decades.

“What I ultimately discovered was that it is quite possible to get research results that were positive, where some kind of technology would enhance a situation in a government or school, or in a clinic,” explains Toyama. “But it was nearly impossible to take that technological idea and then have it have impact at wider scales.”

Ultimately, Toyama came to believe that “technology amplifies underlying human forces. And in our current world, those human forces are aligned in a way that the rich get richer and inequality keeps growing.” But he was open to the idea that if AI could be inserted into a system that was trying to improve equality, then it would be an excellent tool for that.

Technologies can change social and economic systems when access increases, according to Thierry Rayna, an economist who studies innovation and entrepreneurship. He has studied how widespread access to digital music, 3D printing, block chain and other technologies fundamentally change the relationship between producers and consumers. In each of these cases, “increasingly people have become prosumers, meaning they are actively involved in the production process.” Rayna predicts the same will be true with generative AI.

Rayna says that “In a situation where everybody's producing stuff and people are consuming from other people, the main issue is that choice becomes absolutely overwhelming.” Once an economic system reaches this point, according to Rayna, platforms and influences become the wielders of power. But Rayna thinks that once people can not only use AI algorithms, but train their own, “It will probably be the first time in a long time that the platforms will actually be in danger.”

This episode was written and produced by Katie Flood and hosted by Dan Merino. The interim executive producer is Mend Mariwany. Eloise Stevens does our sound design, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe The Conversation's free daily email here. A transcript of this episode will be available soon.

Listen to “The Conversation Weekly” via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

Daniel Merino, Associate Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, Science + Technology Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

Mississippi News7 days ago

What this means for local schools

-

228Sports5 days ago

From Heartbreak to Hoop Dreams: Pascagoula Panthers Springboard from Semifinal Setback to College Courts

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

2 dead, 6 hurt in shooting at Memphis, Tennessee block party: police

-

Mississippi News7 days ago

Willis Miller sentenced to 45 years in prison, mandatory

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Forest landowners can apply for federal emergency loans

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

The unlikely Mississippi politician who could tank Medicaid expansion

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Burnsville man arrested in Prentiss County on drug related charges

-

Mississippi News3 days ago

Cicadas expected to takeover north Mississippi counties soon