Mississippi Today

MAP: Mississippi makes it uniquely hard for low-income new moms to get health care

MAP: Mississippi makes it uniquely hard for low-income new moms to get health care

Low-income women in Mississippi have less access to health care in the months after giving birth than their counterparts in every state except Wyoming.

Mississippi and Wyoming are now the only two states in the country that have neither expanded Medicaid eligibility to low-income working adults, nor extended postpartum Medicaid coverage for new mothers beyond 60 days after birth, according to data compiled by the health nonprofit KFF.

The other nine states that have not expanded Medicaid eligibility have all sought to extend postpartum coverage in recent years. Seven of them, including Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia and South Carolina, have extended coverage to a year after birth. Texas and Wisconsin have sought federal approval to implement shorter extensions of six months and 90 days, respectively.

“We know infant mortality and maternal health are challenges for our state,” said Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican who opposes Medicaid expansion, when he introduced his proposal to extend postpartum coverage in 2020. “One in two Tennessee births are covered through our Medicaid program.”

In Mississippi, that number is higher: about six in 10 births are covered by Medicaid.

During the ongoing COVID-19 federal public health emergency, states are not allowed to kick anyone off Medicaid. As a result, women who have given birth since March 2020 will have coverage until the emergency is lifted, potentially as soon as early 2023.

But ordinarily, a Mississippi woman with two kids and a partner together earning $3,000 a month, for example, would lose her Medicaid coverage two months after her baby is born.

The same woman living in Alabama, which has not expanded Medicaid eligibility but approved a 12-month postpartum coverage extension earlier this year, would have health insurance until her baby is a year old. And the same woman living in Arkansas, which has expanded Medicaid but not extended postpartum coverage, would have health insurance before and after her pregnancy, because she would be eligible based solely on her income.

In Mississippi, women whose pregnancies are covered by Medicaid lose the ability to go to check-ups, get treatment for postpartum depression, and receive care for chronic conditions when their babies are just two months old.

House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, has repeatedly rejected postpartum Medicaid extension, which easily passed the Senate last session. He has described the proposal as Medicaid expansion, though it would not make more people eligible for Medicaid. Almost every other state that has refused to expand Medicaid has nevertheless extended postpartum coverage.

Last week, some of the state's leading doctors told the Senate Medicaid Committee that extending postpartum Medicaid would not only improve abysmal maternal and infant health outcomes but also save money.

Mississippi has the country's highest infant mortality rate and highest rate of premature births. Dr. Anita Henderson, a pediatrician and president of the Mississippi Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said the hospital cost of delivering a healthy baby at full term is typically around $5,000 to $6,000. But an extremely preterm baby requires a long stay in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), at an average cost of $600,000.

State Health Officer Dr. Daniel P. Edney mentioned that Mississippi is one of just two states that has neither extended postpartum coverage nor expanded Medicaid eligibility.

“What I would beg us to consider is the fact it makes much more economic sense to let Medicaid pay for this rather than the state having to pay for it – either state agencies such as the health department paying, or hospitals paying for it with uncompensated care,” he said.

Pregnant women in Mississippi qualify for Medicaid as long as their family income is below 194% of the federal poverty level– about $4,600 per month for a family of four.

But after giving birth, a Mississippian with kids qualifies for Medicaid only if she has a very low income, earning $578 or less monthly for a family of four.

With such a strict income eligibility requirement, it's all but impossible for anyone with a full-time job to qualify for Medicaid coverage. (And healthy adults without kids never qualify for Medicaid in Mississippi.)

In states that have expanded Medicaid, including Louisiana and Arkansas, adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, or about $3,200 for a family of four, qualify for health insurance.

An analysis by the consulting firm Manatt found that expanding eligibility for Medicaid would cut enrollment in pregnancy Medicaid by about half, because many women would qualify based on income alone.

Wil Ervin, deputy administrator for health policy for Mississippi Medicaid, told the Senate Medicaid Committee last week that extending postpartum coverage to a year would cost the state about $7 million.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Capitol sees second day of hundreds rallying for ‘full Medicaid expansion now’

Hundreds of people rallied at the Mississippi Capitol for a second day Wednesday, urging lawmakers to expand Medicaid to provide health coverage for an estimated 200,000 Mississippians.

After faith leaders spoke at the Capitol on Tuesday, Care4Mississippi, a coalition of advocates, held a rally Wednesday. Speakers recounted their struggles with access to affordable health care in Mississippi and chanted for the Legislature to, “Close the coverage gap now,” and for “Full Medicaid expansion now.”

Stephanie Jenkins of McComb, a former social worker, lost her job and health insurance after a car wreck left her with debilitating injuries.

She said she later received some medical treatment from the University of Mississippi Medical Center, but still suffers from chronic pain and other ailments. She said she was told she could not receive Medicaid coverage because she owns too much property.

Jenkins said that years after her accident, “I'm still fighting that battle. I'm still trying to get health insurance. I am still trying to get Medicaid … The state of Mississippi does not realize that it is not about money. It is not about race. It is about people. People are dying because they have no health insurance.”

Dr. Randy Easterling, a Vicksburg family physician and former executive director of the Mississippi Medical Association, spoke in favor of Medicaid expansion. He said the people who would be helped by the expansion primarily work at jobs that do not provide health care and they do not earn enough to purchase private insurance. Many are small business owners.

Easterling said often times the insurance policies available through the federal marketplace exchange have out-of-pocket costs that make them unaffordable for working people if they get sick.

Easterling recounted a story of two of his friends diagnosed with similar cancers. One was uninsured and self-employed, and did not get early diagnosis or treatment. He's now in hospice and on death's door. The other friend, with insurance, received an early diagnosis and treatment and is now cancer free.

“This is a matter of life and death. It is certainly more than a political debate,” Easterling told the crowd.

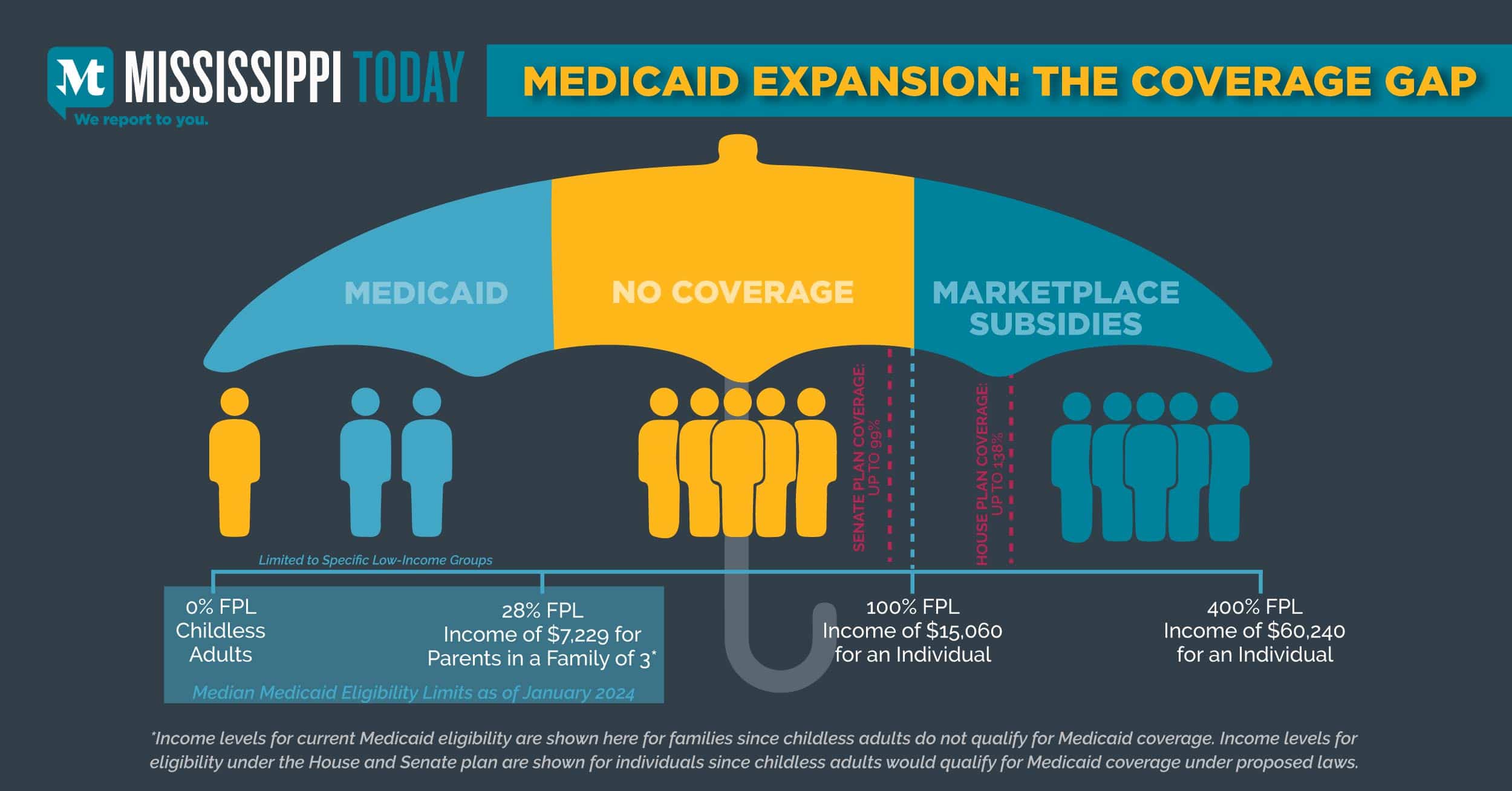

But the issue of expanding Medicaid is currently engulfed in the political process of the Mississippi Legislature. The House has passed a bill to expand Medicaid as is allowed under federal law to cover those earning up to 138% of the federal poverty or about $20,000 annually for an individual. Under the House plan, the federal government would pay 90% of the health care costs and provide the state with almost $700 million more over the first two years as incentive to expand Medicaid as 40 other states have done.

READ MORE: Experts analyze House, Senate Medicaid expansion proposals, offer compromise plan

Under the Senate plan, coverage would be provided to working people earning less than 100% of the federal poverty level and the federal government would pay much less of the costs.

Studies indicate that the Senate plan would cost the state more and cover fewer people. At the rally, people wore yellow T-shirts that read, “close the coverage gap” and “leave no one behind.”

Easterling said that by refusing to expand Medicaid for the last 11 years, “This state has struck a match to $12 billion … and that money was earmarked specifically to increase access to health care.”

He added, “Two days ago most of us wrote a check to the IRS. Now explain to me in simple terms, I am pretty simple, why my (federal) tax money in Mississippi went to increase access to health care in 40 states and not any of it came back to Mississippi.”

“We take federal money right and left,” Easterling said. “We take hundreds of millions of federal dollars for highways, education, the Health Department, law enforcement and natural disasters … But for some reason we push back on additional money for health care. I would submit to you this is a matter of life and death.”

Robin Y. Jackson, with the Mississippi Black Women's Roudtable, told of dropping out of school to care for a family member. In the process she developed a chronic health problem. She said she was unable to get help, but later got a job with health insurance even though her employer knew she had costly medical maladies. After surgeries costing tens of thousands of dollars, she said she is finally well.

“I was lucky,” she said. Others are not so lucky. She said with Medicaid expansion everyone could receive the treatment she was lucky enough to receive.

She said as shepherds of Mississippians, politicians should strive “to leave no one behind.”

Sonya Williams Branes, a former legislator, a small business owner and state policy director for the Southern Poverty Law Center, recounted the struggles she faced with her young son who had chronic asthma. As a small business owner at the time, she struggled to provide health care for her family and her employees.

“To ensure my son remained eligible for CHIP, a program that provided him with vital medical care, I was forced into a corner,” Barnes said. “Making more money, expanding my business and hiring more staff – all paths to improving our lives – would disqualify him from the program, pushing essential health care out of reach.

“Our system is broken,” Barnes said. “It punishes ambition and stifles growth.”

Before the Care4Mississippi rally, the Legislative Black Caucus on Wednesday morning held a press conference calling for adoption of the House's more expansive Medicaid coverage plan.

“We remain committed to having full expansion and covering as many working Mississippians as possible,” said House Minority Leader Robert Johnson, D-Natchez. “Our goal is to sustain health care in Mississippi and sustain it in a way that it doesn't matter where you live or what your income is.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Stories

Mississippi Stories: Natalie Moore

Mississippi Stories: Natalie Moore

In this episode of Mississippi Stories, Mississippi Today Editor-at-Large Marshall Ramsey sits down with Natalie Moore, Peer Wellness Support Services Coordinator for the Mississippi Mental Health Association. Moore and Ramsey share their experiences battling mental health issues and the Congregational Recovery Outreach Program's upcoming mental health summit.

CROP is a faith-based, grant program that aims to help individuals recovering from substance use disorders and mental illnesses.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1863

April 17, 1863

As darkness fell on San Francisco, a young Black woman named Charlotte Brown walked a block from her home on Filbert Street and took a seat on the “whites-only” horse-drawn streetcar.

She and her family had moved to California from Maryland, a part of the city's burgeoning Black middle class. Her father, James E. Brown, was an anti-slavery crusader and was a partner in the Black newspaper, Mirror of the Times.

When the conductor came to collect tickets, she handed him the ticket she had purchased, only for him to refuse to take it.

“He replied that colored persons were not allowed to ride,” she later testified. “I told him I had been in the habit of riding ever since the cars had been running. I answered that I had a great ways to go and I was later than I ought to be.”

The conductor asked her several times to leave. Each time she refused. When a white woman objected to her presence, the conductor grabbed her by the arm and forced her off the streetcar. She boarded twice more with the same result and sued.

Two years later, a jury awarded her the huge sum in her day of $500 (streetcar tickets were just 5 cents), and a judge ruled that barring passengers on the basis of race was illegal. He wrote in his ruling that he had no desire to “perpetuate a relic of barbarism.”

Her victories paved the way for the official end of racial discrimination on streetcars in San Francisco and beyond.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Mississippi News4 days agoMississippi will soon be bombarded with cicadas

-

SuperTalk FM2 days ago

SuperTalk FM2 days ago4 tornadoes touched down in Mississippi during latest round of severe storms

-

SuperTalk FM4 days ago

SuperTalk FM4 days ago2 Jones County correctional officers arrested in smuggling bust

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

Mississippi News5 days agoColumbus schools may see needed upgrades with bond issue

-

Local News3 days ago

Local News3 days agoAlmost 3,500 Mississippi Veterans have enrolled in VA health care in past 365 days, 28% increase over last year

-

SuperTalk FM13 hours ago

SuperTalk FM13 hours agoChance of parole denied for man who killed 3 Choctaw Indian tribal members

-

SuperTalk FM6 days ago

SuperTalk FM6 days agoExplosion at elementary school in Mississippi Delta hospitalizes two employees

-

SuperTalk FM2 days ago

SuperTalk FM2 days agoAmazon project in Madison County to be over $10B, create more jobs than projected: report