Mississippi Today

Authentic: Leach did it his way, changed football in the process

Authentic: Leach did it his way, changed football in the process

Mississippi State football coach Mike Leach, who died last night at the age of 61, was nothing if not authentic. There was only one of him. He was unique.He was special.

I wish I had known him better. But here's what I do know: Leach was remarkably bright, intellectually curious, and innovative person who just happened to coach football. He would have been successful at whatever he chose to do. He just happened to choose football. His life story reads like something out of Ripley's Believe it or Not.

Start with this:He never really played football, but he changed the way the sport is played at every level. He and Hal Mumme devised the Air Raid offense at a little NAIA school called Iowa Wesleyan. Now, nearly everybody uses some version — or at least some of the principles — of that spread-the-field, no-huddle offense.

I loved the way Leach put in his book — “Swing Your Sword” —when he was writing about what he and Mumme were doing at Iowa Wesleyan: “We were changing the geometry of the game.”

They were. Nearly everybody else was lining up their offensive linemen shoulder to shoulder, Leach and Mumme were splitting their linemen at least a yard apart. Nearly every other team was huddling between downs, as teams had done since the sport was invented. Iowa Wesleyan skipped the huddle all together. Everybody else was running the ball most of the time and passing occasionally. Leach and Mumme threw it on almost every play, often using crossing patterns that had the defense running into one another like The Tree Stooges. Most coaches called plays from the sidelines and the quarterback, if he wanted to remain the quarterback, ran those plays as ordered. Iowa Wesleyan gave the quarterback the freedom to change the play at the line of scrimmage.

PODCAST: Mike Leach, remembered.

Iowa Wesleyan was 0-10 the year before the arrival of Mumme and Leach. They were 7-4 in their first season and then won 17 over the next two years. As Leach put it, “I was the offensive line coach, the offensive coordinator, the recruiting coordinator, the equipment manager, the video coordinator and the sport information director. I also taught two classes.”

His salary was $12,000 a year. Keep in mind, he could have been a lawyer making many times that. Also keep in mind, when Leach died, he was making $5.5 million a year to coach at Mississippi State.

Mumme and Leach won at Iowa Wesleyan, then Valdosta State, then Kentucky. Leach then went to Oklahoma for one year before becoming a head coach at Texas Tech. His head coaching career consisted of three stops: Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State — places where you are the underdog competing against the likes of Texas, Oklahoma, Southern Cal, Washington, Alabama and LSU. Despite that, his teams won 158 games and lost 107 and went to bowl games in 18 of his 22 years.

It's funny: I can remember, years ago, many discussions about whether Leach's offense would translate in the Southeastern Conference where teams primarily ran the ball and won with ball control and defense. Hell, by the time Leach finally came to the SEC nearly everybody in the league, including Alabama, was running some version of his offense.

No, Leach has not, to use the hackneyed phrase, “set the world on fire” during this three seasons at Mississippi State. But his Bulldogs surely were trending in the right direction, from 4-7 in year one, to 7-6 in 2021, to 8-4 this season. He was getting there.

Leach's arrival at Mississippi State coincided with the pandemic, the biggest reason why I didn't get to know him better than I did. It's difficult to really get to know someone in zoom meetings. Indeed, the most time I ever spent with him was in 2011, when he was on a book tour between his stints as Texas Tech and Washington State. We met at Lemuria and drank several cups of coffee over three hours outside at Broad Street Baking Company and Cafe. Funny thing: He was a football coach and I was a sports writer and we talked about football for maybe five minutes total. Another funny thing: It was Houston Nutt's last season at Ole Miss and Vanderbilt had just blasted the Rebels 30-7. Many folks were mentioning Leach as Nutt's possible replacement. We could see passers-by putting two and two together and whispering.

I remember talking to Leach about going from Pepperdine law school (where he accumulated $45,000 debt from student loans) to a $3,000 a year coaching job.

“I was going to give it two or three years then get back to being a lawyer and make some money,” he said, chuckling. “I got hooked.”

We call all be thankful he did. He has made football far more fun. The outpouring of respect and admiration these past few days speaks volumes.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1892

April 22, 1892

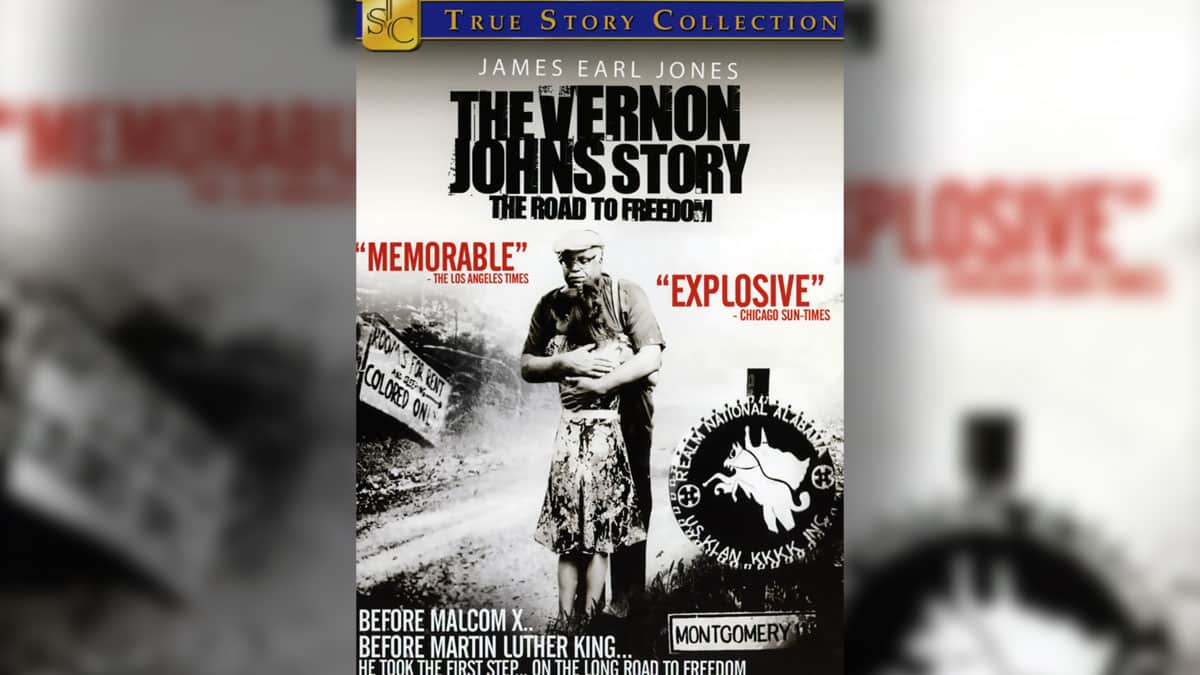

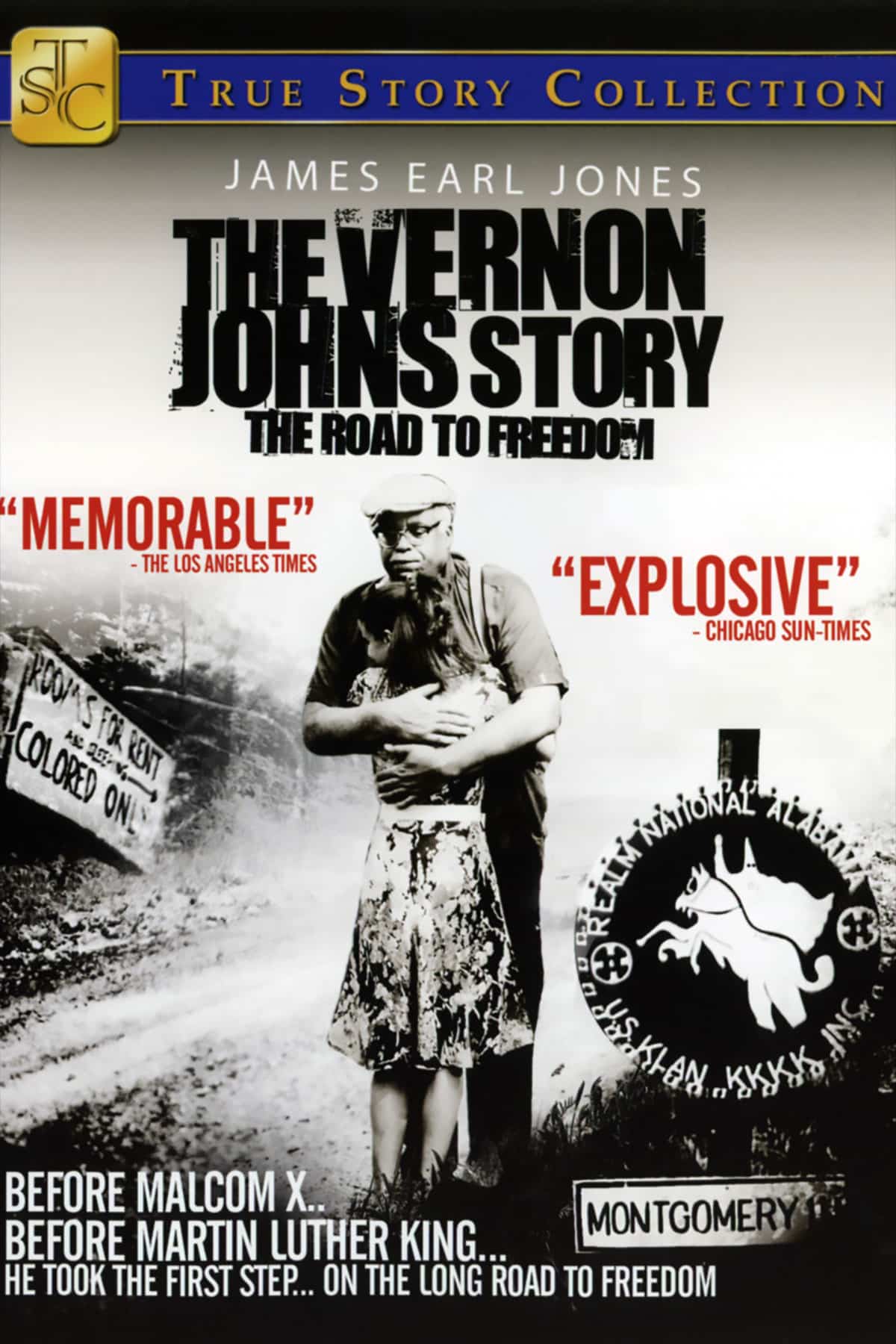

Fiery civil rights pioneer Vernon Johns was born in Darlington Heights, Virginia, in Prince Edward County. He taught himself German and other languages so well that when the dean of Oberlin College handed him a book of German scripture, Johns easily passed, won admission and became the top student at Oberlin College.

In 1948, the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, hired Johns, who mesmerized the crowd with his photographic memory of scripture. But he butted heads with the middle-class congregation when he chastised members for disliking muddy manual labor, selling cabbages, hams and watermelons on the streets near the state capitol.

He pressed civil rights issues, helping Black rape victims bring their cases to authorities, ordering a meal from a white restaurant and refusing to sit in the back of a bus. No one in the congregation followed his lead, and turmoil continued to rise between the pastor and his parishioners.

In May 1953, he resigned, returning to his family farm. His successor? A young preacher named Martin Luther King Jr.

James Earl Jones portrayed the eccentric pastor in the 1994 TV film, “Road to Freedom: The Vernon Johns Story,” and historian Taylor Branch profiled Johns in his Pulitzer-winning “Parting the Waters; America in the King Years 1954-63.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=351711

Mississippi Today

Podcast: Rep. Sam Creekmore says Legislature is making progress on public health, mental health reforms

House Public Health Chairman Sam Creekmore, R-New Albany, tells Mississippi Today's Geoff Pender and Taylor Vance he's hopeful he and other negotiators can strike a deal on Medicaid expansion to address dire issues in the unhealthiest state.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=351583

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1966

April 21, 1966

Milton Olive III became the first Black soldier awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in the Vietnam War.

Olive had known tragedy in his life, his mother dying when he was only four hours old. He spent his early youth on Chicago's South Side and then moved to Lexington, Mississippi, where he stayed with his grandparents.

In 1964, he attended one of the Mississippi Freedom Schools, and he joined the work in Freedom Summer, registering Black voters. Concerned that he might be killed, his grandmother sent him back to Chicago, where he joined the military on his 18th birthday.

“You said I was crazy for joining up,” he wrote. “Well, I've gone you one better. I'm now an official U.S. Army Paratrooper.”

He joined the U.S. Army's 173rd Airborne Brigade and became known as “Preacher” for his quiet demeanor and his tendency to avoid cursing. On Oct. 22, 1965, helicopters dropped Olive and the 3rd Platoon of Company B into a dense jungle near Saigon. They returned fire on the Viet Cong, who retreated. As the soldiers pursued the enemy, a grenade was thrown into the middle of them. Olive grabbed the grenade and fell on it, absorbing the blast with his body.

“It was the most incredible display of selfless bravery I ever witnessed,” the platoon commander said.

Olive saved his fellow soldier's lives. Then-President Lyndon B. Johnson presented the medal to his father and stepmother, and he has since been honored with a park and a junior college named for him.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

SuperTalk FM6 days ago

Chance of parole denied for man who killed 3 Choctaw Indian tribal members

-

SuperTalk FM5 days ago

2 arrested after missing man’s body found on side of Mississippi highway

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

What this means for local schools

-

Kaiser Health News6 days ago

To Stop Fentanyl Deaths in Philadelphia, Knocking on Doors and Handing Out Overdose Kits

-

228Sports2 days ago

From Heartbreak to Hoop Dreams: Pascagoula Panthers Springboard from Semifinal Setback to College Courts

-

Mississippi News2 days ago

2 dead, 6 hurt in shooting at Memphis, Tennessee block party: police

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Willis Miller sentenced to 45 years in prison, mandatory

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

The unlikely Mississippi politician who could tank Medicaid expansion